The Most Insane 12 Days of Muskie Fishing in Wisconsin History

This story, “The Twelve Days,” appeared in the September 1956 issue of Outdoor Life.

A few minutes before midnight of October 29, 1955, Tony Burmek and his brother Fred set out from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on a trip that produced one of the most incredible catches of muskellunge in the history of this unpredictable sport.

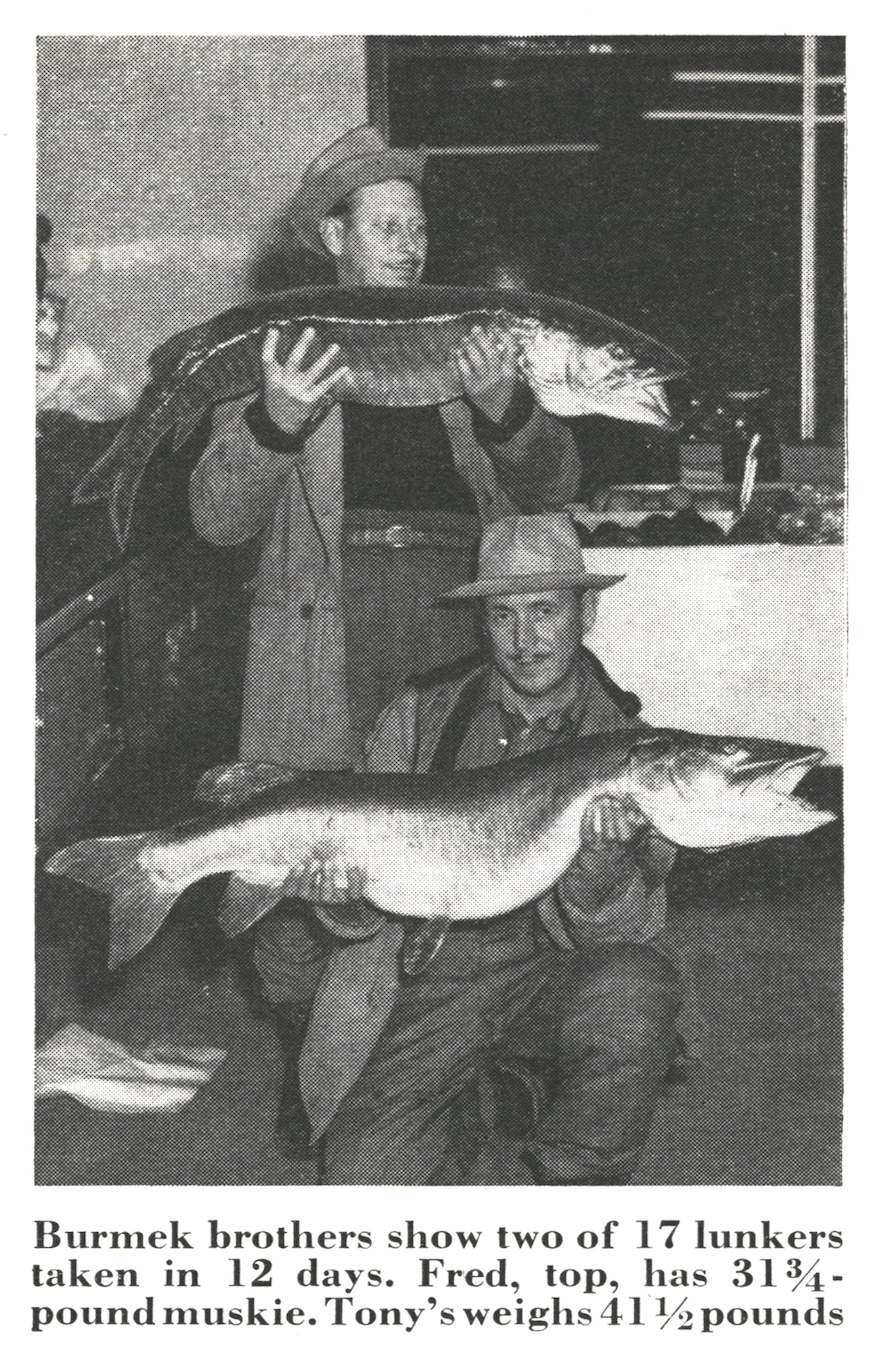

At the end of 12 days of fishing, much of it in weather that froze lines to rods and started the first ice of the season creeping out from the shores of Sawyer County lakes, Tony and his partner had brought 17 muskies into the little Wisconsin town of Hayward. The smallest was a 25-pounder, many were over 30 pounds, and one of them, at 43 1/8 pounds, was the largest muskie reported from the Hayward sector that year.

Almost from the first day of their fishing, October 30, when they caught a 31¾-pounder and a 38½-pounder, the Burmek brothers had Hayward popping with excitement. That’s quite an achievement, for Hayward calls itself “the muskie capital of the world.” Day after day the Burmeks fished, often in freezing winds which made it impossible to hold a boat over a bar long enough to get in two casts. And each evening they came back to town with their fish, mostly of trophy size.

Haywardites wondered how long the Burmek luck would hold. And they speculated, as fishermen will, that the Burmeks might be getting their monsters with setlines or by using suckers for bait, a deadly method that’s quite legal but considered unsporting by many.

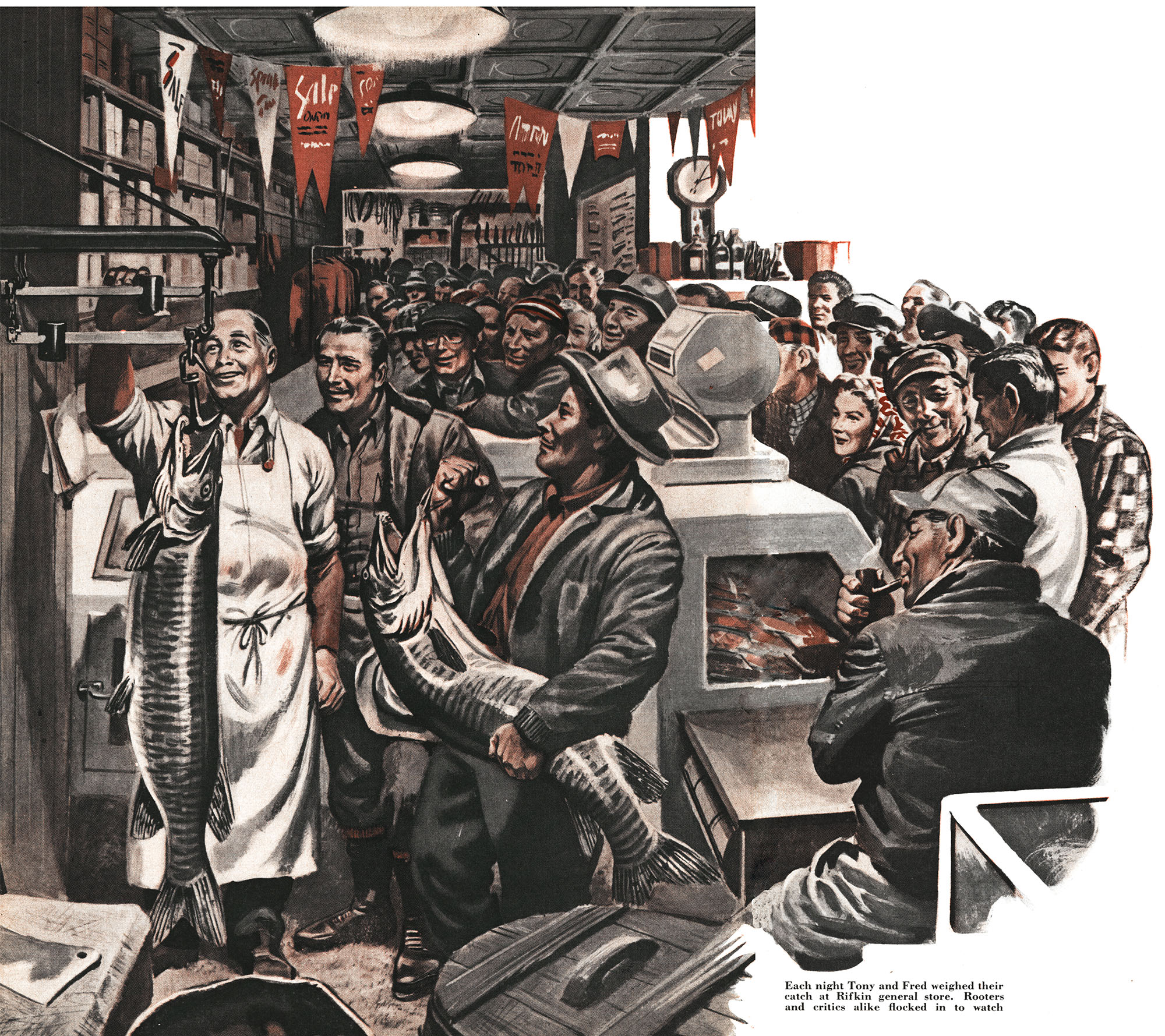

Having been directed to the Rifkin general store in Hayward to weigh their first day’s catch, the Burmeks thereafter weighed all their muskies at Rifkin’s. Fred and Tony drove to and from the dock in a station wagon, and folks soon began flocking to the store when the station wagon pulled in each night.

Like baseball fans following a player on a home-run spree, local people became increasingly interested as the Burmeks piled up more muskies. Eventually as many as 50 persons would crowd around the scales, and Julian Gingras, who publishes the weekly Sawyer County Record, mused that he’d like to have a daily paper to run a box score for readers who were now rooting for Fred and Tony.

When the 12 days were over the Burmek muskie take totaled 533¼ pounds, plus 26 pounds for a single northern pike. They gave fish away as they caught them, and freezers in Hayward began filling up with muskies that would have to be cut in two to get them into ovens.

The statistics of the Burmek catch can be had from almost anyone in Hayward, or from the newspapers. But over and above the statistics, impressive as they are, is the story of a real fisherman, Tony Burmek. Tony, who makes most of his living guiding fishermen on the waters around Hayward, is 43 years old. For 20-odd years he has done little else but fish for muskies.

There are any number who are “crazy about fishing,” but almost always these anglers vary their sport by pursuit of different species. Not Tony. Tony fishes for muskies, nothing else. I have known this shy, courteous guide for 10 years, and if he had the literary ability of an Ernest Hemingway, he could write a book about muskies that would be a classic of its kind.

Tony got interested in muskies in 1934, while visiting relations in the Hayward country. Since then he’s devoted most of each summer to studying these fish, especially those in Sawyer County lakes. If he spots a good fish he’ll keep after it for weeks.

He believes that the best fishing is when the barometer is rising. There’s nothing new in that. But there is in the way Tony carries out the barometer’s orders. When it starts a sensational climb, Tony will drop anything to get on muskie water.

He also uses contour maps. These, too, are available to all anglers. Of the more than 8,000 lakes in Wisconsin, some 1,200 have been contoured, a fine job done back in the C.C.C. days. But in 20 years there have been slight changes from silting, so Tony, the perfectionist makes annual airplane flights over the lakes to study variations in the bars. Once he found a productive reef that wasn’t shown on a contour map.

When Tony and Fred left Milwaukee late that October night, they had no idea they were going to write a startling page in Wisconsin muskie fishing. On the way north they ran into a little snow. When they got to Hayward the barometer was low.

By noon of that first day the barometer climbed from 29.75 to 29.90, temperature was 39, wind west, sky over cast. That was enough for Tony. He and Fred put a boat in Round Lake, six miles east of Hayward. This is a “name” muskie lake of 3,276 acres, in a class with neighboring lakes such as Grindstone, Lac Court Oreilles, Teal, Lostland, and Ghost.

It was to be drift fishing in mid-lake over bars Tony knows well and which few others bother with. Fred chose a homemade plug whittled out by Tony two years before. In its few earlier tests this plug had failed, so it had been forgotten in a tackle box.

On his third cast Fred hooked a small muskie and released it. In the time it took the boat to drift 20 feet or so, Tony, casting with the same plug, hooked a muskie which weighed 38½ pounds. That fish shook the hook as it lay exhausted alongside the boat, but Fred got a net under the fish and heaved it aboard.

You’ll get no long stories from Tony about fights with fish. He says, “You get one hooked solid and you play him instinctively. The big moment in muskie fishing is when you get the fish to strike.

Back over a mid-lake bar they went. It was Fred’s turn with the homemade plug. He took a muskie that went 31 1/4 pounds — the biggest male, Tony says, he’s ever seen. Big muskies are females, usually.

Most of the fish taken on this trip struck upward in deep water, sometimes in spots where the bottom was 25 feet straight down. The plug, which has a violent tail action, was kept three or four feet below the surface. Tony says maybe other lures would have worked as well. He doesn’t know. He and Fred stayed with the one that was producing.

There’s a theory in the north that muskies go on feeding sprees in late autumn, and Tony is a strong supporter of this idea. But, as he says, “Just try to get the general public out on those lakes in late October or November.”

Here in Wisconsin it’s well known that after Labor Day, and the opening of schools, the fishing lakes are deserted. You could rake the Chippewa flowage with cannon fire and endanger nary a fisherman.

Like baseball fans following a player on a home-run spree, local people became increasingly interested as the Burmeks piled up more muskies. Eventually as many as 50 persons would crowd around the scales.

The second day found the Burmeks back on Round Lake — barometer higher, wind still west, temperature 38. Tony’s diary records laconically that they didn’t get onto the lake until noon because “All the Hayward folks were around us talking muskie fishing.”

Over the mid-lake bars in the first half hour they each released muskies. The wind picked up, the boat pounded. They went inshore, and off a point in deep water Tony hooked one. “It didn’t rush toward the bait on the surface like you see ’em do in summer,” says Tony. “Just one lunge up from the bottom, then, boom,” Tony boated that fish. It weighed 28 pounds.

The third day was warmer. It was cloudy, with an east wind. Over the bars in the middle of Round Lake they drifted for two hours, releasing three fish weighing more than 12 pounds apiece. They moved in to the point of the previous day, caught an 18-pounder and released it.

The next fish hit a long way out from the boat. It was big. Tony saw the whole plug outside the muskie’s mouth. He knew it was lightly hooked, and for15 minutes he sweated it out. Fred saved the show. He got a gaff into the fish just as the plug dropped out. This one weighed 48½ pounds.

It was the biggest muskie of the Hayward area for the season — up to that moment. They took that fish right into Hayward, left it there, and returned to Big Round after lunch.

That afternoon over a mid-lake bar Fred felt that familiar jolt of a fish coming up from below. “We had quite a time with this one,” Tony’s diary re cords. “He wouldn’t surface. I rowed quite a way with him. Then he came up. Fred worked him in close and I shot him with a pistol. The fish weighed 36 pounds.”

By the end of the third day, all Hayward was talking of the Burmek brothers. Publisher Gingras made a date to go with them next day, then had to cancel it.

For the fourth straight day they tried Round Lake. Fred lost a medium-size fish and then, over those same mid-lake bars, caught a 26-pound northern pike. (Both the Burmeks will tell you that big northerns fight as hard as big muskies.) After the northern, Fred got an 18-pound muskie and released it. It was one of their coldest days, the day knuckles started to bleed from chapping. Tony further battered his knuckles playing a 31-pounder that beat up his numbed fingers with the reel handle.

Snow shoveling was the order of the fifth day. The Burmeks scooped the snow out of their boat on Round Lake and worked Leder’s Bay. Each hooked and released small fish. Tony had decided to rest the mid-lake bars. Off White’s Point Fred hooked, played, and shot a 29-pounder. At the entrance to Hidden Bay, Tony hooked and released a small one. Then, well inside the bay, Tony took a 26 1/4-pounder.

Monotonous? “No,” says Tony. “There was extra fun in getting into Hayward every night with those fish. We had the skeptics looking pretty sick.”

On the sixth day the Burmeks almost surrendered to the cold. They worked Round Lake for two hours. Fred caught and released a small muskie and they went ashore and started a fire. In later afternoon Tony took a muskie off Pine Point that weighed 33 pounds. Fred released a small one. They quit.

On the seventh day Fred put back a muskie he estimated at 25 pounds. The fish was played a long time and was exhausted. To revive it they slipped it into a wet gunny sack and sloshed the sack back and forth in the water to make the gills open and shut, thus forcing oxygen to the fish.

This was Fred’s last day with his brother. He took one more muskie of about 14 pounds, returned it, and called it quits. Shortly afterward Tony wound up the day with a 25-pounder. It was the smallest of the 17 muskies the Burmeks displayed in Hayward.

On the eighth day Fred was on his way back to Milwaukee. With the barometer at 30, highest of the entire period, Tony went alone to the sprawling Chippewa flowage — the famous “Big Chip” known to muskie madmen from many states. It holds the world muskie record, a 69 pound 11 ounce fish taken in October of 1949, and is one of the great muskie-producing waters of the continent.

Using the same plug and system to fish over the Church Bars of the flowage, Tony caught and released a little one. Then he motored to the narrows, took a 30-pounder, and was back in Hayward by supper-time.

At this juncture Tony was wishing he had 100 all-out muskie fishermen with him. “I’d have assigned them to different lakes,” he says, “so we could nm a real test. I suspect the muskies were hitting everywhere.”

Again alone on the ninth day, Tony tried Lac Court Oreilles, a 4,827-acre lake famous among the muskie faithful since before the turn of the century. There was six inches of snow on the ground. Tony remembers that day very well: “There’s a point on this lake — Winter’s Point — and it looked like it was named right that day. I drifted across the point once, hooked and released a small one. On the next drift I took a 27-pounder.”

That night there was a hard freeze and on the following day Tony didn’t fish. But he was back at the muskie bars the next day, this time with Clayton (Sergeant) Slack, flowage resort operator, for a partner.

Over Andres Bar, Slack took a 38¾ pound muskie. Tony released one hooked off Muskie Point and on the next drift across the same point boated a 28-pounder.

By now Hayward was buzzing, if not seething, over the fantastic Burmek campaign. The nightly weighing at the general store was drawing onlookers like a circus sideshow. Burmek muskies were displayed on ice in the glass case at the Moccasin Bar. And people were talking. A few thought Tony might be violating the law by having too many fish “in possession,” the possession limit being only one muskie a day. But Tony — and Fred, too — gave away each day’s trophy before going after an other. Some skeptics still thought the Burmek haul was the result of some mysterious and unsporting system. However, most people, among them George Curran, state game manager at Hayward, simply accepted it as a run of good luck by persistent and expert muskie fishermen.

On the 11th day the barometer was rising. Again Slack was Tony’s partner and again they fished the big flow age. In the first hour Tony released three fish. He thinks one weighed about 20 pounds. Then he hooked and shot a 28½-pounder.

He and Slack went ashore for lunch. Back at it again in the afternoon, Slack hooked and lost a really big one. Tony doesn’t know how big it was. He never saw it. Slack kept on casting and before the end of the afternoon boated a 37½ pounder.

At this point the Burmek diary gets about as emotional as the Burmek diary gets. Tony recorded: “Slack was beside himself with excitement.”

Tony was getting tired. The daily routine of bucking wind and waves, the constant cold, the wet, cracked hands, the bleeding knuckles — all were taking their toll.

Tony didn’t want to go out that final, 12th day. But Slack was keyed up and Tony agreed to one hour of fishing, no more. It was so cold they welcomed chances to trade off casting and warm up with the oars. Slack’s young son was with them and it got too cold for him to fish. The hour passed but Slack persuaded Tony to stay a bit longer.

The next and final fish of the trip was caught by Tony. It weighed 431/s pounds, biggest muskie of the season in the Hayward region.

Final score was 17 muskies boated in 12 days. The men released 22 and counted a total of 42 that struck, either to be killed, lost, or released.

It’s not hard in Hayward today to find people who question the Burmek feats in one way or another. Tony’s own good reputation is the best answer to those who whisper. I have to go along with Tony, knowing him as I do.

Tony and Fred had a lot of things on their side. They know these waters. They know how to make a plug run the gamut of its possibilities — shallow, deep, slow, fast, side-to-side, up-anddown. They had the muskie grounds almost entirely to themselves, and that’s important. These were fish that hadn’t been showered with hardware day in, day out. And the fish were obviously on the feed just before the freeze-up.

Most important of all, the Burmeks had the benefit of Tony’s 20-odd years of devotion to the sport. A man like Tony Burmek develops a knowledge of fish and fishing that he finds difficult to transmit to others.

Muskies do queer things. They go for long periods without striking and then go on rampages. At Chicago’s Shedd aquarium, which Wisconsin keeps supplied with muskies for display, they’ve had captive muskies that refused to eat for six months, still remained apparently healthy, finally began to eat.

“Ten thousand casts for one strike,” is the old and familiar catch phrase of the muskie fan. But that pattern can change violently, as witness the performance at Leech Lake, Minnesota, last summer. There muskies were boated by the score in water which had never in living memory produced such fishing. The Leech Lake spree has never been explained by biologists; they just know it happened.

It’s not hard in Hayward today to find people who question the Burmek feats in one way or another. Tony’s own good reputation is the best answer to those who whisper.

From now on Tony Burmek will be a marked man in Hayward muskie country. When he clicks — and he will — people will say, “After all, this guy is a pro. All he does is fish for muskies.” If he flops — and he’ll do that too — the Monday-morning quarterbacks of muskie fishing will have a fine time. Fortunately for Tony, he has the disposition of a friendly St. Bernard pup, and underlying that, in great depth, he’s as stolid as a clam.

I asked him if he thought he could duplicate last autumn’s performance. “Perhaps not,” he said. I asked if he was just lucky. “Yes, very lucky — but I’ve always been lucky fishing for muskies.”

Tony also knows the weak spots in the offense of the casual muskie fisher man: “They use rods that are fine for bass, no good for hooking muskies. You need a stiff rod for muskies. And many people get so attached to their equipment they forget about the fish. Watch a fellow with a fancy multiplying reel. He’ll get into a casting rut, like a hypnotized man. The guy casts and retrieves, casts and retrieves — same motions, same speeds, same distance of casts.

“Thing to do is try everything in the book. Cast short and cast long. Reel fast and reel slow, with rod high, rod low. And as you crank, manipulate the rod, up and down, back and forth. Do everything you can think of to give the plug variation.

“Another thing — too many muskie fishermen stick to the shoreline. Find the bars out in the middle and work them over. You don’t just fish those bars. You explore them.

Read Next: The Legend of Muskie Joe, the Man Who Searched His Whole Life for a 6-Foot Fish

“If you get a roll out of a good fish, toss out a marker on a sinker and come back in an hour. Often a quick change of lures will provoke a muskie into an other dash. I use little cork floats for this purpose, hard to see in the waves, but then I don’t want others to see them and try for a fish I’ve roused.”

And, finally, Tony has this to say: “Autumn is far and away the best time. The muskie fisherman who’s willing to go out and work through rough water and weather will do all right.”

The post The Most Insane 12 Days of Muskie Fishing in Wisconsin History appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/fishing/bermek-brothers-muskie-fishing-stories/