Snowmelt, Goats and Other Hazards

Skiing a big face in July in Utah feels like it should be a contradiction. But, after a record year of snowfall, such a thing appeared to be a very real possibility. This is a story of my attempt to do just that.

Standing above the glacially polished quartzite and the deep blue meltwater that fills Lake Blanche is the craggy hump that is Dromedary Peak. After hiking there for the first time in late June, I was admittedly a little underwhelmed. Compared to the nearby majesty of Sundial Peak or the sheer cliffs of the cirque at the base of Monte Cristo, Dromedary is not particularly remarkable. It’s just somewhat tall, at 11,103 feet, and shaped like the hump of a Camel. But one thing about it caught my eye more than anything else in that valley: snow covering a decent amount of the northeastern face. Not a lot of snow, but enough to drool over.

It took me three weeks to return to Dromedary. In that time, I almost forgot about what I had seen, being my first summer in the Wasatch I spent my free time hiking something new, and skied more accessible lines like the north couloir of Mt Olympus and suicide chute. Realizing that the opportunity to ski down was disappearing fast, and that the ideal time to ski off of Dromedary was most likely well in the past, I rallied to at least make an attempt for July 1st.

That morning I ended up being heavily delayed, and as a result I didn’t get moving out the door and onto the trailhead until noon. It was not the best start, but I was motivated to make my way up the mountain and get at least one run in before dark. I was joined on this hike by my climbing buddy, Adrian. Adrian would not be skiing but would be accompanying me for the majority of the climb.

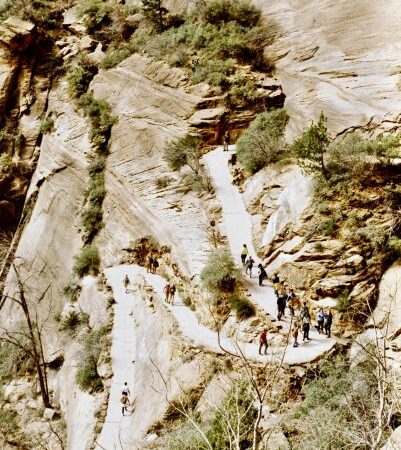

Parking at the Mill B South trailhead, we made our way up towards Lake Blanche. I carried along with me some hiking essentials like water, food and some extra clothing, as well as my ice tools, including an ice axe and automatic crampons for my ski boots. Strapped to the outside of my pack I had my skis with boots locked into the bindings. While not a difficult hike, at around three and a half miles and 2800 feet in elevation, the afternoon sun and the load I carried made this segment of the journey quite difficult. By the time I made it to the top I was drenched in sweat. So, we stopped to rest at Lake Blanche before traversing around the bottoms of the lakes and crossing over the dam at Lake Lillian.

This is where the hike up stopped being straightforward. We moved upwards until we reached a series of exposed rock drumlins which fill the valley. Formed when glaciers scoured out large fins of bedrock, these obstacles needed to be crossed in order to reach the valley at the base of Dromedary Peak.

It was climbing these where we encountered our first major challenge. We had to eventually get off of the fins and cross into the cirque. The rock fins dropped off sharply into the snow, some 20 feet below us. Climbing down was not too difficult despite the added weight on my back because the rock here offers plenty of handholds. However, thanks to the warm temperatures and rapidly melting snow, a wide randkluft had formed where the snow had melted away from the warmer rock. Unable to dismount, we had to traverse clinging to the rock face until we could safely get onto the snow. Here we found our next task: navigating safely across a valley that was melting out from underneath.

The danger in this was clear. I could see the multitude of fast-moving streams that were converging under the very snowpack we needed to cross. This hidden threat was visible in a few places where the snowpack had caved in, and whitewater boiled underneath. Not knowing what one is walking over is sketchy, and in situations like these we found a methodical testing of each footstep with a probe was the best way to ensure a safe crossing. Progress across the valley was slow and despite our best efforts our feet still occasionally punched through. But by using exposed rocks as a crossing point, we made it safely over the stream and up to the other side of the valley to begin our climb in earnest.

It was here where we had to have a revaluation of options. My initial plan from here was to put on my boots and crampons and climb the remaining 2000 feet up a chute, through a bowl and up a final couloir before coming down the same way. This was no longer an option. Many of the cliffs were partly, if not fully exposed and the chute I had seen weeks earlier had rotted out to bare rock. Plan B was down a similar line; a north westerly facing chute about ten feet wide. However, looking at the crux of the climb, I realized that this would be a bad idea. While this is a line to drool over, given the current conditions safe access to the top of the chute would have been dubious at best.

Running out of daylight and options, I decided to change plans and take a route that, while not a direct descent, appeared significantly easier to downclimb through the bare sections of exposed cliff. There was a slight catch; a good portion of this route was covered in prickly bushes that we had to scramble through.

With the sun fading behind the north ridge and shadows quickly creeping over the face, I left Adrian on a rock outcropping with my camera and started the climb towards the top. The snow climbing was ideal, as the sun cupped névé made for good climbing. I made my way up to the base of a large cliff at about 10,600 feet. I cut a shelf, took off my crampons and began my descent down about 1300 feet.

In my excitement I had forgotten to secure my phone and it fell somewhere along the run. So, upon reaching the bottom I had to climb up again and look for it. And I have to say, wandering around two thirds up a mountain at sunset in crampons looking for a phone was a surreal experience. This fun was short-lived. The crash of rocks above us alerted us to a family of mountain goats having a snack on a shelf a few hundred feet up. Getting out of there gave us a full view of the failing light illuminating the entire valley below.

It was here we ran into a party of backpackers cooking on the rocks enjoying the sunset. We sat with them for a while and talked about the experience while spotting mountain goats. It was refreshing to run into people who show similar enthusiasm for being in the mountains and doing nothing more than enjoying the experience.

The glow of the sunset accompanied us as we passed down through the lakes and began the three-mile hike down in the moonlight. Hopefully I get to do this again. There is potential to ski some incredible lines off this peak and adjacent ridges. Even in late spring where the snowpack is rapidly melting, multiple lines of couloirs and chutes cutting through staggered bands of cliffs allow one ski the entire way down. I can only imagine how epic this peak is in the winter when everything is buried. One day I might get to drop in from the very summit itself. Until then, I consider this story open ended.

The post Snowmelt, Goats and Other Hazards appeared first on Wasatch Magazine.

Source: https://wasatchmag.com/snowmelt-goats-and-other-hazards/