President Teddy Roosevelt Conserved Millions of Acres of Federal Lands. It Was His Greatest Legacy

This story, Teddy Roosevelet’s American Game Trails,” appeared in the January 1991 issue of Outdoor Life.

Ask most Americans to name five presidents and, chances are, Theodore Roosevelt will be among them. Without question, T.R. was one of the most memorable characters to ever occupy the White House. With his thick, pince-nez spectacles, bristling mustache and horselike teeth, his looks alone made him hard to forget.

His accomplishments also were in a class apart. Besides having a political career that took him from the New York State Assembly to the highest office in the nation, he was also a cattleman, an ornithologist, a taxidermist, an explorer, a military hero and a prolific writer whose books and articles covered subjects as diverse as the life of Oliver Cromwell and the Hopi Snake Dance.

The one constant force in T.R.’s phenomenal life was his passion for wild things. This fascination with nature began during his boyhood on Long Island, New York, where young. Teddy devoted his leisure hours to studying birds, collecting natural “artifacts” for his “museum” and learning the art of taxidermy. By the time he finished Harvard in 1880, Roosevelt was recognized in scientific circles as an accomplished naturalist. He. had also developed a taste for the outdoors that could not be satisfied by the tame environs of the East.

Like many an adventurous young man of that day, T.R. headed West. “It was still the Wild West in those days,” T.R. later wrote, “the West of Frederic Remington’s drawings … of the Indian and the buffalo hunter, the soldier and the cowpuncher. It was a land of vast silent places, of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at the passing horseman.” In short, it was Teddy’s kind of place.

Despite a total lack of experience with livestock, he bought two cattle ranches, the Elk Horn and the Chimney Butte, along the Little Missouri in the badlands of present-day North Dakota. While he still maintained his home in the East, over the next nine years, Teddy’s ranch house became his spiritual headquarters. Much of his time during those days was spent hunting, both on the plains near his ranches and in the mountains to the north and to the west. His reminiscences of those years, recorded in a trilogy of hunting books (Hunting Trip of a Ranchman, Ranchlife and the Hunting Trail and The Wilderness Hunter), are now classics of American big-game hunting lore.

“When the friends of the special interests in the Senate woke up, they discovered that 16 million acres of timberland had been saved for the people … before the land grabbers could get at them.”

-Teddy roosevelet

The rugged, hardy life of the frontier excited Roosevelt even more than the abundance of big game. When recounting an antelope hunt in the Badlands of the Dakotas, Roosevelt stated, “The number of cartridges spent compared to the number of pronghorn killed was enormous, but the fun and excitement of the chase were the main objects … the actual killing of game was of entirely secondary importance.”

Teddy found his own abilities tested on more than a few occasions. In a 1908 article for Everybody’s Magazine, he recalled how something as seemingly simple as a Christmas deer hunt could suddenly turn into near tragedy in the wilderness.

T.R. and one of his cowhands were returning from a successful hunt, each with a whitetail slung behind his saddle. A frozen river lay between them and home. Not realizing that a recent spell of unseasonably mild weather had weakened the stream’s covering of ice, the two men urged their heavily laden mounts onto the frozen river. “About midway,” Teddy wrote, “there was a sudden, tremendous crash, and men, horses and deer were scrambling together in the water amid slabs of floating ice.” Fortunately, the river was shallow, “and no worse work resulted than some hard work and a chilly bath. But what cared we? We were returning triumphant with our Christmas dinner!”

Disaster once more stalked Roosevelt in Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene country. While searching for goat sign along a mountain ridge, T.R. lost his footing. Before he could recover his balance, he slid headlong over the brink of a steep ledge and fell into the top of a pine tree below, which broke his fall. Roosevelt came to rest in the crown of a small balsam fir some 60 feet from where his flight had begun, everything intact but his dignity.

That close call didn’t dull T.R.’s keenness for adventure one whit. Later that same day, he prevailed upon his companions, John Willis and Bill Merrifield, to lower him by lariat over the edge of a 300-foot canyon wall to give him a better photographic angle on an especially spectacular waterfall. His mission completed, T.R. signaled for Merrifield and Willis to hoist him up. To their dismay, they found their combined strength insufficient to bring Roosevelt back to the top. He dangled over the rapids below for two hours while his partners frantically sought a way out of the predicament. Finally, in desperation, they lowered him even farther into the canyon, playing out all of the line they had between them. When at the literal end of his tether, T.R. tossed his camera down to Merrifield (who had walked around and gotten down below him) for safekeeping, then plunged 25 feet into the rapids below. He surfaced downstream, soggy, but otherwise in “bully” condition.

Once, while hunting alone in Montana’s Bitterroot Range, Teddy found his quarry itself to be the source of some unbargained for adventure. Slipping through the pines surrounding his camp, Teddy spied an oversize grizzly padding along the woodland floor. The shot was a close one, and Teddy took slow, deliberate aim.

He shot, and the grizzly crashed off into a laurel thicket. Long seconds passed as Teddy waited, unsure of his next move. Without warning, the bear appeared on the hillside above the laurel scrub, searching the woods below for his enemy. Again Roosevelt fired. This time, instead of fleeing, “the great bear turned with a harsh roar of fury and challenge, blowing the bloody foam from his mouth, so that I saw the gleam of his white fangs; and then he charged straight at me. …”

T.R. shot a third time, slamming the bear with a chest shot that ran the length of the bruin’s body — but the grizzly came on. Roosevelt jacked his fourth and last round into the chamber. Matadorlike, he leaped aside, barely avoiding the beast’s claws, and fired his final shot as the bear passed by.

The bear fell, apparently dead, a few yards from where Roosevelt was standing. T.R., his rifle empty, watched in horror as the grizzly regained his feet. Roosevelt clumsily struggled to replenish the spent magazine. But a fifth shot was not to be necessary. The bear’s head dropped, and the grizzly fell for the last time.

Teddy’s rather heroic accounts of his hunting exploits prompted his detractors to brand him a braggart and a blowhard. Certainly T.R. was no shrinking violet; he didn’t mind telling others of his accomplishments. And he was an exceptionally skilled outdoorsman, a fact that has caused his name to appear on the pages of this magazine numerous times over the years.

In a 1932 Outdoor Life article, for instance, Texas hunter John “Catch ‘Em Alive” Abernathy recalled how the president had kept up with him on an exceptionally grueling wolf hunt across a prairie-dog-burrowed landscape, even when saddle-toughened cowboys in the group had dropped out of the chase. “He deserved more credit for staying with me in that hazardous race than I did for catching the wolf. For the president … to have outridden several seasoned, daredevil riders on the hard 10-mile race was no mean accomplishment.”

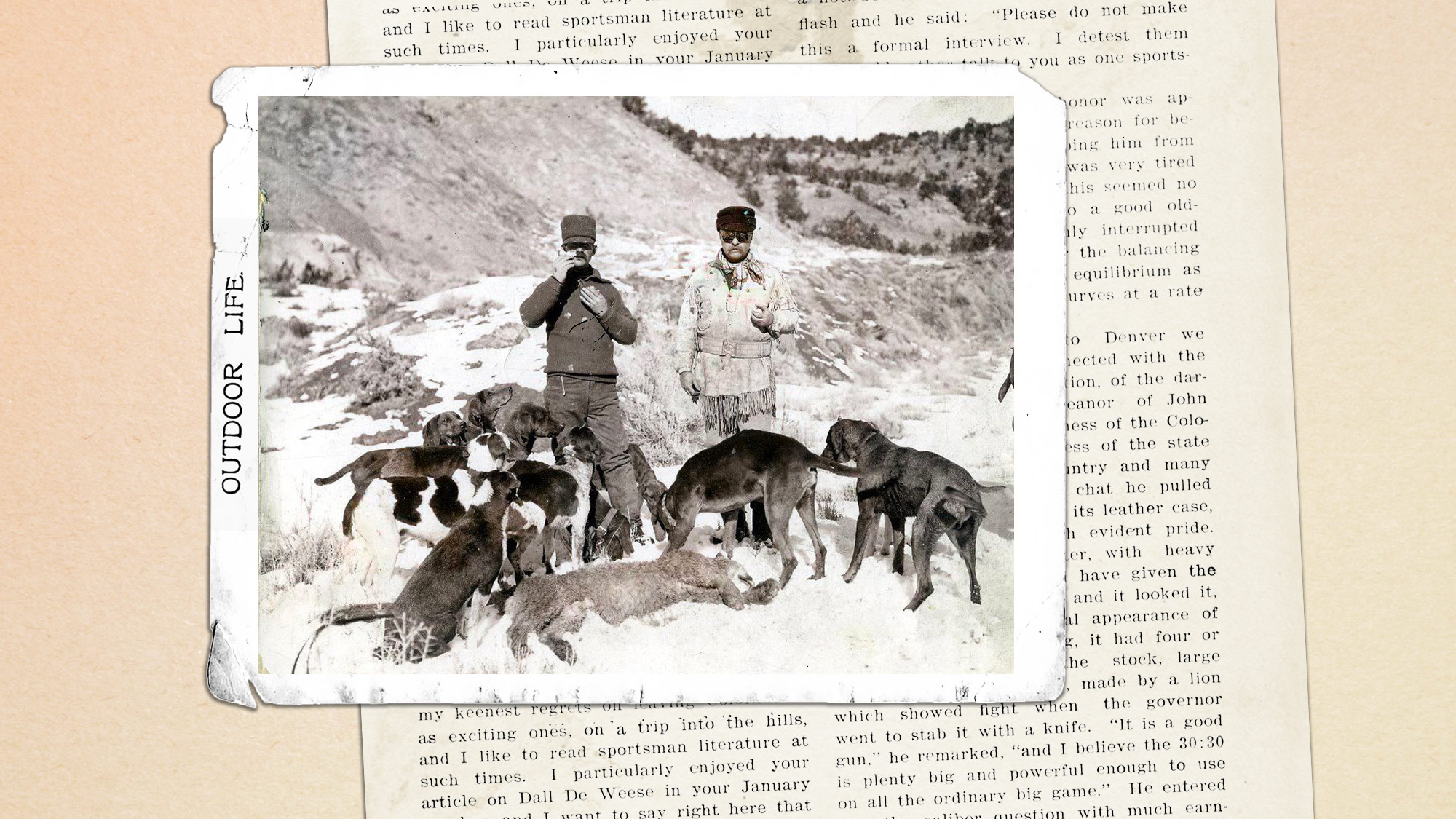

As cougar hunter John Lesowski noted in a July 1967 article in Outdoor Life, while hunting in Colorado in 1901, Teddy Roosevelt shot one of the largest mountain lions ever killed. It weighed 227 pounds, wrote Lesowski, and its skull was the first recorded in the Boone and Crockett Club record book. The cougar still stands as the fourth biggest ever recorded in Boone and Crockett.

Related: Our Editor-in-Chief Interviews Teddy Roosevelt After His Mountain Lion Hunt, From the Archives

Despite his successes, T.R. freely confessed his own mistakes and inadequacies as candidly as he detailed his triumphs, often making himself the butt of his own jokes in the process. In Hunting Trip of a Ranchman, for instance, he somewhat sheepishly admitted that he had on more than one occasion stealthily approached what he took to be a black bear only to discover that the object of his stalk was a charred log.

Roosevelt’s writings placed him among the foremost authorities of his day on American big-game animals, but his fascination with wildlife extended beyond the beasts of the chase. The tiny creatures of the wild, too, took much of his attention, and his hunting books are filled with digressions concerning his observations of the lesser birds and beasts of the field. In The Wilderness Hunter, for example, Roosevelt slips from a first-person narrative of a stalk for pronghorns into a five-page discussion of the relative musical merits of the Western skylark and the Southern mockingbird. Later, in the same book, he just as effortlessly shifts from a recap of a caribou hunt into an eyewitness account of the bloodthirsty hunting habits of the tiny water shrew.

Teddy’s preoccupation with all aspects of the outdoors quite naturally drew him to the fore of that first awakening of environmental activism. In 1888, he, along with Forest and Stream editor George Bird Grinnel, founded the Boone and Crockett Club, for which T.R. served as president for six years. From its very beginning, Boone and Crockett was actively involved in the protection of wildlife habitat. Among its early successes was the passage by Congress of the 1894 Protection Act (for which the club vigorously lobbied), which brought a halt to the game slaughter, timber cutting and mindless commercial development that then threatened Yellowstone National Park.

In 1901, after two years as governor of New York, Teddy was elected vice-president of the United States. The following year, while hunting in the Adirondacks in upstate New York, Roosevelt received word that President McKinley had been seriously injured during an assassination attempt. Eight days later, McKinley succumbed to his wounds, and T.R. became the 26th president of the United States.

The “bully pulpit,” as Teddy called his new office, offered him the greatest opportunity of his life to advance his conservation agenda, and he took fullest advantage of it. Forest protection ranked high on T.R. ‘s list of priorities, and he made liberal use of a law that allowed the president, by proclamation, to transfer federally owned lands into the national forest system. As might be expected, he met with considerable opposition. But to Teddy, politics were just another occasion for adventure, and in true T.R. style, he triumphed.

One of Teddy’s most decisive victories over the foes of conservation came in 1907, when his opponents secured an amendment to that year’s agricultural appropriations bill barring T.R. from placing any more federal land in the northwestern United States under the administration of the Forest Service. The bill passed, and it was to become law within a matter of days unless vetoed by the president (something T.R. did not wish to do). The special-interest groups thought they had T.R. over a barrel.

“But for four years,” Teddy later wrote, “the Forest Service had been gathering field notes as to what forests ought to be set aside in [the affected] States.” Working feverishly against the four-day deadline, T.R. and National Forest chief Gifford Pinchot converted that rough data into a plan to create national forests in the Northwest. “When the friends of the special interests in the Senate … woke up,” Teddy gleefully recalled in his autobiography, “they discovered that 16 million acres of timberland had been saved for the people … before the land grabbers could get at them.”

By the end of his second term, the total national forest acreage had increased from 43 million to 194 million.

But that was far from the sum of T.R.’s contributions to the protection of woodlands and wildlife. According to Roosevelt’s own account, his administration saw the number of national parks double; the establishment of four big-game refuges and 51 bird sanctuaries; the enactment of the first Alaskan game laws; the establishment of an 18,000-acre National Bison Range in Montana; the passage of the National Monuments Act; and the convening of the first national conference on conservation.

In the midst of all that activity, Teddy still found time for a hunting trip or two. In 1902 he went South to Mississippi’s Yazoo Delta to undertake a mounted bear hunt “after the fashion of the old Southern planters. The president’s guide for this excursion was Holt Collier, a bear hunter and dog handler of such prowess that his name is still remembered in parts of Mississippi today, a half-century after his death. Despite Collier’s best efforts, the choreography of hound, horse and bruin necessary to allow the president the shot he wanted never quite materialized. It looked as if Teddy was to be disappointed.

By the end of Roosevelt’s second term, the total national forest acreage had increased from 43 million to 194 million.

But Collier was determined to please the president, and, finally, he and his hounds managed to bring a bear to bay in a dense canebrake. Although many stories circulate about what actually happened, apparently Collier, whose bear hunting tactics were rooted more in meat-hunting practicality than in gentlemanly notions of sportsmanship, roped the bear, · drove it back to the presidential camp, and tied the defeated beast to a tree. Roosevelt was summoned to administer the coup de grace.

T.R. took one look at the pitiable prisoner and declined to shoot. To kill a bear under such conditions, he said, simply would not be sporting. Roosevelt’s refusal was subsequently caricatured in a popular editorial cartoon entitled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi.” Enterprising businessmen capitalized on the event by bestowing the name “Teddy” on a style of stuffed toy bears that has been popular ever since.

Roosevelt held a great deal of contempt for the wanton destruction of wildlife — especially where the killing was for commercial purposes. Market hunters, Roosevelt believed, “had no excuse of any kind” for their nefarious activities. He reserved his highest scorn, though, for that “certain class of wealthy people” who purchased the meat, hides and heads of animals the professionals killed. “There is always an element of the absurd [in] trophies of the chase which have been acquired by purchase,” Roosevelt said.

On the other hand, Roosevelt maintained that “very little appreciable harm” was ever done to game populations by legitimate sportsmen hunting for food or trophies. Blind opposition to “all hunting of game,” he firmly believed, was “a sign of softness of head, not of soundness of heart.”

The anti-hunting element was particularly incensed over the president’s celebrated 1903 trip to Yellowstone National Park with poet-naturalist John Burroughs. Hunting, of course, was prohibited in Yellowstone, and the anti-hunters, convinced that T.R. planned to try for big game during the outing, were more than a little disturbed about the president’s intended visit to that great Rocky Mountain wildlife reserve.

T.R. did break the no-hunting rule — but just barely. As Burroughs and Roosevelt were riding cross-country in a touring sleigh, Burroughs recalled, “the president jumped out, and, with his soft hat as a shield to his hand and, captured a mouse that was running along over the ground near us. He wanted it for [U.S. Biological Survey Chief] Dr. [Hart] Merriam, on the chance that it might be a new species.” The rodent, it turned out, was not new to science, but Roosevelt was the first to document its presence in the park.

After leaving the White House, T.R. expanded his hunter-naturalist career to new horizons. In 1909, he led a highly publicized and highly successful expedition to Africa to secure big-game specimens for the Smithsonian Institution. His account of the trip, entitled African Game Trails, did much to popularize African safaris among American big-game hunters. In 1962, more than a half-century later, American sportsmen would still be enjoying T.R.’s trip, retraced by his great-grandson, Jonathan Roosevelt, on the pages of Outdoor Life.

What was perhaps Roosevelt’s most ambitious project came in 1913, when, in cooperation with the Brazilian government, he set out to explore the River of Doubt, a stream of the wild interior of the Amazon Basin, so named because its route through the jungle was, quite literally, unknown.

For once in T.R.’s heroic life, it looked as if his great teeth had bitten off more than he could chew. Too many years away from the hardihood of ranch life had added inches to his waist and softened his once rugged frame. Moreover, the jungle expedition faced every imaginable hardship: impassable waterfalls and death-dealing rapids; short rations; swarms of biting, stinging insects; malaria and dysentery; even the threat of attack by hostile natives. By the time the group reached civilization, it had spent two months in the Brazilian jungles and covered 1,500 miserable miles of previously unexplored wilderness.

T.R., now feeling the reigns of old age tugging on him, would never be the same robust man again. He returned to his family home at Sagamore Hill to a quiet life of reading and writing. He died in his sleep in the early hours of January 6, 1919.

“Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die,” Teddy wrote shortly before his death, “and none are fit to die who have shrunk from the joy of life and the duty of life. Both life and death are parts of the same Great Adventure.”

No one will ever accuse Teddy Roosevelt of having shrunk from joy or duty, and certainly not of having shrunk from adventure. Indeed, adventure is his legacy to us today.

Jim McCafferty is the author of a children’s book entitled Holt And The Teddy Bear about Theodore Roosevelt’s famed Mississippi black bear hunt, which was the legendary birthplace of the “Teddy Bear.”

The post President Teddy Roosevelt Conserved Millions of Acres of Federal Lands. It Was His Greatest Legacy appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/conservation/teddy-roosevelt-conservation-legacy/