Of Calm and Consequence

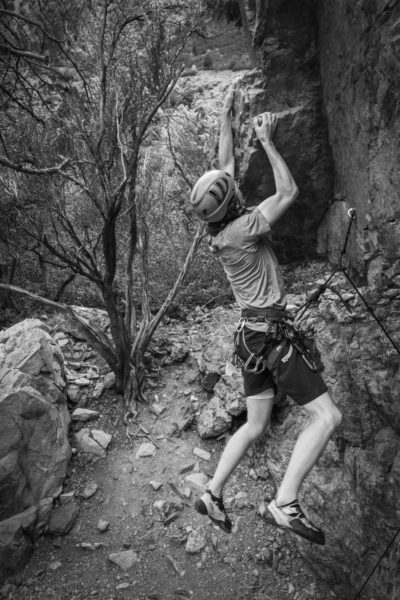

I take a moment to breathe and consciously relax my muscles before trusting my hands and feet to carry me one move further up What the Hell, a sport climb high on the north side of Little Cottonwood canyon. Secure on the wall, I crane my neck upwards to spot my next bolt, the next point where I can reset my fall distance. I can just make it out, maybe ten feet further up the wall; I look down to my previous bolt, a ponderous 20 feet or so below my current position. The way lead climbing—what I happened to be doing at the time—works, if I fall right now I would fall at least forty feet, and every foot I climb up to the next bolt increases that fall by two more feet. If I fell while clipping my next bolt, I could fall sixty feet. To make matters sketchier, most of What the Hell is sloped at less than 90 degrees, so instead of falling into the air and letting the rope catch me, I would be bouncing and sliding off of the sharp and unforgiving wall.

That amount of fall potential is not representative of all lead routes, of course, but one aspect of this climb is fairly universal to popular forms of outdoor climbing: even with proper gear and taking the right precautions, losing your grip or choosing the wrong footing can lead to scrapes, bruises, broken bones, or worse. This is true of many other “extreme” outdoor sports; skiing, mountain biking, river rafting, dirt biking, canyoneering, and so forth all carry very proximal risks for failing to execute simple tasks. People I know will often hear stories like the one I opened with and ask, “then why do you do it?” or “doesn’t that scare you?” There are multiple answers to the first question—and those answers are neither unchanging nor universal—but one of those answers for me, is partially related to the answer to the second question: “yes.”

To examine this a bit further, let’s think about the reasons anyone does anything that might result in harm. One reason might be to impress someone else. Another reason someone might do something dangerous is for an intrinsic desire to improve and excel, or to do something that brings them joy along with the danger. Another might want the experience of accomplishing or learning something. There are many more reasons one might have (I’m sure you have a few reasons of your own) but I am of the opinion that perhaps most often, we accept some amount of danger because there is no other good option. As nerve-wracking as the potential of a big fall onto jagged rocks is, it pales in comparison to some of the situations I’ve been in that I had no control over, and I know for a fact that I have seen far from the worst the world has to offer.

I realize that makes it sound like I once had to walk a swaying, fraying rope bridge across a chasm or some such heroics, which is fortunately not the case. What I want you to consider is that relatively few of the perilous situations we find ourselves in are because of outdoor sports; actually, outdoor sports make up only a small percentage of the risky/difficult activities that humanity participates in regularly. This is especially true when one remembers that there are kinds of risk and danger besides physical danger: disappointment, loneliness, sadness, and more are our companions along with physical pain in the pursuit of life.

Take the following instance: my family blended when I was in my mid-teens (read: my brothers and I packed up and moved in with a new stepmom and stepsiblings), a situation that was far more stressful for me than a dark, spider-filled pitch in Robbers’ Roost slot canyon (also, quite stressful). And worse, I had almost no practice dealing with this situation; how could I have? As such, I had quite a strugglesome time for a couple of years. Now, in my early twenties, stressful situations have (alas) not been pulling their punches. The hallmarks of adult American life—navigating higher education, finding a job, using the money from said job to pay bills (why are there so many), dating, keeping a healthy social life, these are all things that are virtually necessary and yet failure to execute them effectively could have serious consequences.

Outdoor sports are extraordinary because they have the powerful ability to bottle up stress, fear, and danger, and make the price of failure so clear and concrete, that one must confront these fears directly in order to become great at them. Lead climbing is my favorite example of this because it is so crystal clear and has taught me so much; when I first started, any amount of climbing above my last bolt sent my legs shaking and my forearms overgripping. Far from lessening the risk to my safety, these nervous tics made successful climbing much more difficult as my feet gripped the wall with less stability and my arms tired at an alarming rate. This, in turn, made me more nervous, which made me shakier, and so on in a vicious cycle of unsending.

As a lover of the send, this vicious cycle was something I could not allow to continue. To overcome it I had to learn to trust my own abilities, and my equipment, and my belayer, and the techniques my mentors had taught me. Slowly, I grew more confident. My legs stopped shaking and I stopped death-gripping the wall. Leading became a relaxing mental exercise where I learned to quell the persistent fear that said “sure, you’ve held on hundreds of times, but what if you fell this time?” It became a time for me to concentrate fully on the problem at hand without worrying that I would make a mistake and fall catastrophically. It became a time to practice putting my trust in others, and to strengthen my weakness (thoroughness—not my strong suit—is very important when checking that you’ve tied your climbing knot correctly).

I will add that I did not stop being cautious. I like being cautious, and safety is key when it comes to these outdoor sports. What I did stop doing was letting the fear of making a silly mistake turn into a mental distraction.

Over time, I began to see this creep into other aspects of my life. Participating in important meetings, or introducing myself to someone I wanted to make a good impression on, have long been stressful for me in a way similar to how lead climbing was; I’ve been in many meetings, and I’ve gotten pretty good at meeting people, so worrying about making a mistake was doing nothing but hindering my progress. Now, I’m much better at adopting the same mindset I have when I’m on the wall: concentrating on the task at hand, trusting my abilities and the people around me, and making stuff happen.

It was while pondering this little transformation that I came to this conclusion: perhaps one of the reasons we go to the mountains, or to the sea, or to the sky, is because they teach us to control our minds, to focus, to act calmly in intense situations, to trust where we need to trust and strengthen where we are weak.

Because sometimes life just throws you an intense situation. And I love sports like rock climbing, even though they might scare me a bit, for letting me practice for when it does.

The post Of Calm and Consequence appeared first on Wasatch Magazine.