My Wife and I Tried to Walk Home in an Arctic Storm. We Almost Died

Point Lay, Alaska, epitomizes the extreme Arctic. Winter on the Northwest Alaska coast is marked by unrelenting winds. Windchills routinely reach 75 degrees below zero. Whiteout conditions restrict visibility to mere inches. Throw in two months of complete darkness — plus hungry polar bears — and the vision of this Arctic village becomes even more formidable.

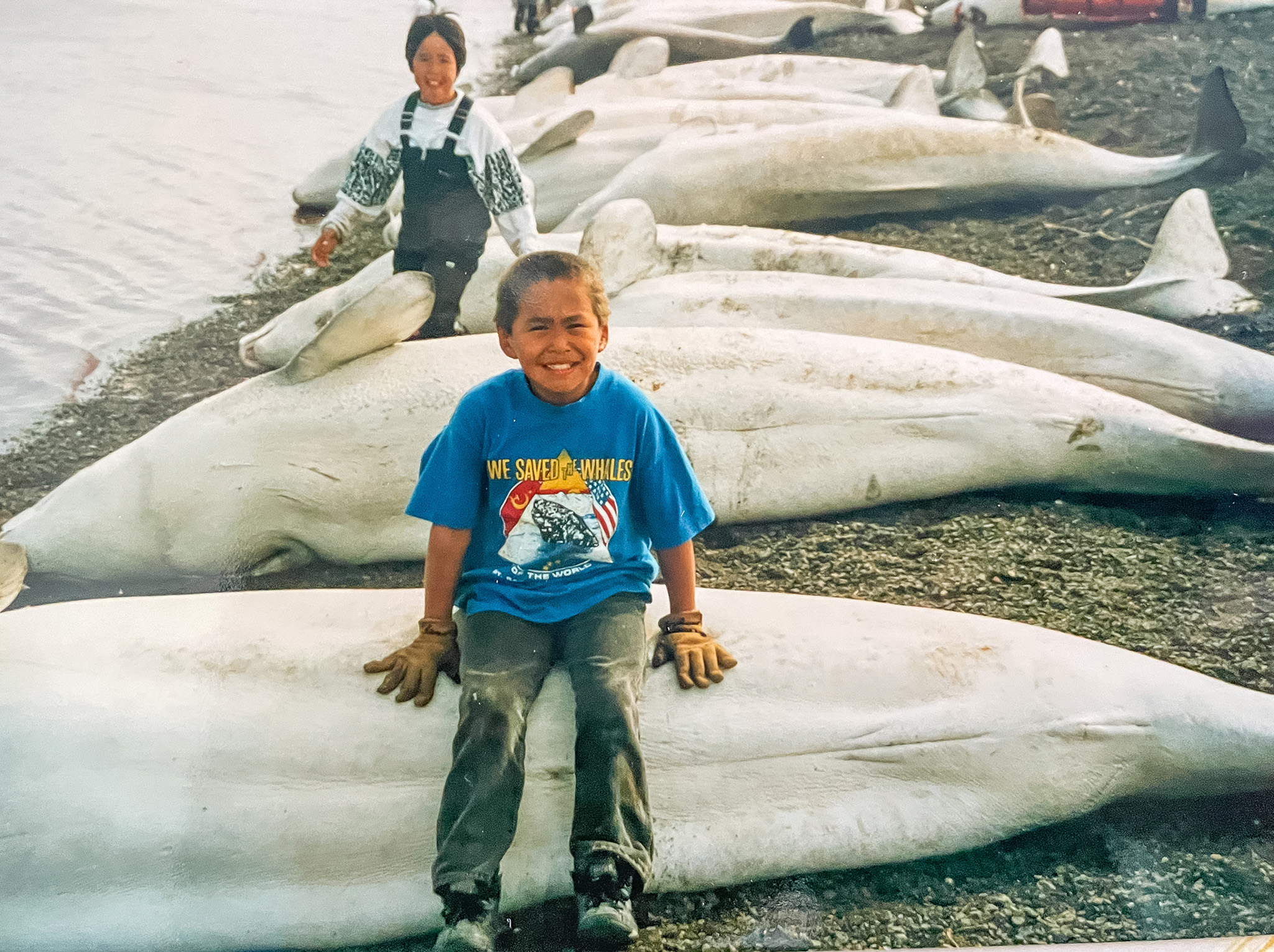

This is where my wife, Tiffany, and I lived for three years. Our jobs as schoolteachers took us there in 1990. At the time, fewer than 100 residents lived in this remote Inupiat village, where remnants of sod houses built with whale ribs for beams still stood. No stores were operating, and if we wanted meat, we hunted and fished for it. Previous generations had dug ice cellars deep into the permafrost, and our neighbors still used them.

Here, the sterile, ice-laden landscape is unforgiving and one mistake can cost you your life. The first year we lived in Point Lay, Tiffany and I experienced 199 straight days of below-zero temperatures. Not below freezing, mind you — below zero. It was on one of those days that Tiffany and I nearly died.

Into the Blizzard

I’ve faced man-eating lions in South Africa and a man-eating polar bear in Alaska. I’ve survived plane crashes, sinking vessels, and being held at gun point in Mexico. They all pale in comparison to the day I walked home from work with my wife.

It was Friday, Feb. 15, 1991, and Tiffany and I had lived in Point Lay for six months. There were only a half-dozen service vehicles in the village and less than a mile of roads; there was no need to own a car. We could walk from one end of town to the other in minutes. So we headed to school that morning wrapped in our usual winter garb: work clothes bundled underneath heavy down jackets and pants, snow boots, gloves, hats and scarves. Winds that day topped 50 miles per hour, yet the snow blanketing the ground hadn’t been blowing much. Visibility was fine, and I left my goggles at home.

The storm intensified as the morning passed. Winds continued to build and sweep away snow. Drifts had begun forming between buildings and visibility had shrunk to 50 yards by 10 a.m., and our administrator decided to close school. The kindergarteners slipped their fur parkas over their heads and pulled on their mukluks, or caribou skin boots. On their way out, many grabbed the bags of coal they had laid by the door upon their arrival that morning. The coal added weight to keep them from blowing over in the winds. Young children were escorted home by older kids or parents, and soon everyone had left school and made it home safely. Everyone except me and Tiffany.

By noon visibility had dropped to 10 feet. Even though our house was just 100 yards from the school, we lingered, hoping conditions would improve. But three hours passed and the storm only intensified. Twilight was quickly turning to dark, and we made up our minds. I called the principal, who had gone home earlier. He warned us not to take our usual shortcut. He had just heard a warning over the CB radio that downed power lines were dangling a few feet above the newly-formed snowdrifts. Instead, we would have to take the road.

Taking the road sounded easy enough, but this meant instead of traveling in a direct line, we would now have to make two key turns along the way. We had not taken this route in the past five months, which wouldn’t matter in most conditions. Now, however, we would have to negotiate large snowdrifts and elevated berms.

Rather than spend the night at the school, Tiffany and I decided to battle the elements and head for home. I told the principal our intended route and said I would phone again when we reached home. If he didn’t hear from us in 10 minutes, I told him, call Search and Rescue.

We bundled up and stepped outside. We were nearly blown off our feet by the blizzard. Winds blasted in excess 75 miles per hour, with gusts close to the century mark. With windchill, the temperature was close to 120 degrees below zero.

Visibility topped out at 5 feet. But the big, two-story building we wanted to reach was just across the road, and on the corner of our first turn. Leaning into the wind, Tiffany and I locked elbows and began walking. Within 10 paces the school had disappeared in blowing snow behind us.

In such violent winds, the simple task of breathing is arduous. It sucks the breath right out of your mouth. The only way to breathe is to cover your face entirely with your hood and take a deep lungful of air, holding it as long as possible. As we walked, the thought of suffocating crossed my mind more than once. It was also virtually impossible for us to communicate; the wind took the words out of our mouths before we could make a sound.

We couldn’t see the big building until we were two steps from it. Its scant shelter gave us a pocket out of the wind that allowed us to talk, but even shouting we could barely hear each other. The storm was deafening. It felt as if we were standing behind the engines of a 747 lifting off the runway.

Still, I felt confident. I knew the location of the next check point. It was a house on the right-hand corner of the street, some 60 yards straight ahead. Though I couldn’t see that house — or any of the other houses fewer than 20 yards from us — I knew the direction we had to walk. If I could guide us directly north, in a straight line down the road to this next point, we could make it safely home. From the house on the corner, we would simply turn right and follow three houses in a row until we reached ours.

Leaning into the wind again, we headed straight down the road. Within a few steps it became impossible to differentiate the snow-covered road from the snow blanketing the tundra. We stumbled over small drifts that had accumulated in our path. Visibility was so poor we could not see our feet through the sheets of blowing snow.

Tiffany tugged at my arm, a signal to stop. She had tucked her head completely inside her jacket and now, instead of escaping, the moisture from her breath had frozen her glasses to her face. I anchored her as she tried poking a bulky glove through her hood and scarf to remove the useless glasses, but she had to remove the glove. She slid her bare hand to her face, pried off her glasses, and slipped them into an interior pocket. When she reached for her glove, it was gone, swept away by the wind.

She pulled her bare hand deep inside her sleeve to prevent frostbite, and we slogged on.

For the next 30 yards we walked under power poles, the snapped electrical lines dangling mere feet above us. The electrons in the dry Arctic air and friction of the high winds allowed the voltage coursing through the power lines to shoot electricity straight down to earth, shocking us with every step we took. It was all we could do to hold onto each other as we received shock after excruciating shock. Some jolts were so powerful, they nearly knocked us off our feet.

At the height of this electrocution and just halfway down the road, we plowed face-first into a snowdrift. I maintained contact with the drift by extending an arm and skirting along to the leeward side, searching for a low point to eventually cross. Finally, we reached a section of the drift that tapered off enough to climb it. We crawled on our hands and knees a short distance up the drift. I distinctly recall thinking to myself that whatever happened, I had to keep my bearings on the straight line we were ultimately walking.

As we stood exposed atop the giant heap of snow, the wind blasted us harder than ever. Attempting to descend the opposite side of the drift, I set my foot down into empty air, and lost my balance.

We had two choices. We could find a place where the snow would blow over us and cover our bodies entirely to insulate us from the storm. Or we could push on.

The fierce wind had carved out the backside of the snowdrift, creating a vertical drop. Instead of letting go of Tiffany, I held her tightly so we both tumbled end over end, all the way to the bottom. As we lay in a heap, I finally realized the severity of the danger we faced. The wind was so powerful, carrying so much wet snow, that simply finding which way up was daunting. In the fall, I had lost all sense of direction. Tiffany’s hood had been yanked off and she struggled to re-button it, exposing her bare hand.

Frostbite was a risk, and now hypothermia entered the equation. Despite our heavy clothing, our arms and legs were numb. Our hands had lost all dexterity and the cold was seeping into our torsos. Both of us lost total control of our facial muscles, making it impossible to move our jaws to form words. Our skulls pounded as if they would burst. I’ll never forget the searing pain in my head and throat — a pain like I had never known.

Panic set it.

Weighing Our Chances

There was one thing I had prided myself on throughout the many years I spent outdoors: I had never been lost. With the aid of a compass, GPS, or my natural instincts, I had always managed to find my way back to camp. That confidence helped reassure me now. It was, ironically, this same confidence that got us into the predicament.

We had two choices. We could find a place where the snow would blow over us and cover our bodies entirely to insulate us from the storm. Or we could push on.

If we stopped now and let the snow drift over our bodies, there was no telling when the storm would subside or how many feet beneath packed snow we would be trapped when it was all over. I decided to fight the storm and try to walk home.

So we started moving again. After trudging some 30 yards in what felt like a straight line, I became worried we had not yet hit a house — any house. My heart sank and a sick feeling settled in my stomach. For the first time I questioned my navigation: we weren’t heading in the direction I had thought.

I had no idea where we were and had no way of finding out. We stood in a violent, swirling whiteout. Our bodies were weakening, and we needed to find shelter as quickly as possible. As I tried to calculate our next move, I began to shake violently — not from the cold, but from the realization that death was knocking. For the first time in my life I felt I was on the losing end of a battle for survival. The storm was winning.

Then, I felt a rush of adrenaline coursing through my body like never before. Decisiveness seized me. We had to move — now.

We took two strides and a wall materialized five feet away. We had been mere yards from the house and unable to see it. We huddled in its shelter and tried to regain our composure.

I recognized the house, and I realized our error. The whole time I thought we were traveling east, we were actually heading west. If we hadn’t bumped into that house, we would have died. One more step to the left would have led us right past the last building on the outskirts of the village and onto the frozen Arctic Ocean, just 50 yards away. Our bodies would have likely gone undiscovered until the spring thaw, another four months away.

Not Home Yet

Huddled against the safety of the house, the winds whirled around the roof and sides, creating a backdraft that slapped us in the face. It was all we could do to breathe. We tried walking one way around the house, but ran face-first into an immense snowdrift. Instead of climbing another snowdrift and getting turned around once more, we retreated. Bringing our heads together, we tried forming an air pocket with our hoods. I felt my face becoming engulfed by the moisture of our breaths and within seconds my eyelids froze shut, as did Tiffany’s. Reaching up with one hand, I broke the ice free from our eyelashes. Again, they froze shut and again I broke them free. We violently banged on the side of the house, hoping to be heard over the driving storm.

A face appeared in the dark window above us. The person was trying to signal to us, but we couldn’t see well enough to understand. Then they put on a white glove, which stood out in the gloom of the window. They pointed us in the direction to move and, after battling an eight-foot high drift, we made it to their front steps — or at least, where their front steps were buried beneath five feet of snow.

Within seconds my eyelids froze shut, as did Tiffany’s. Reaching up with one hand, I broke the ice free from our eyelashes. Again, they froze shut and again I broke them free. We violently banged on the side of the house, hoping to be heard over the driving storm.

As we stumbled into the warm room in a state of semi-shock, Inupiat children huddled around us. The man of the house, Willard Neakok, sternly declared he would guide us safely home. We had no time to protest, only to briefly thaw our faces. The last thing Tiffany and I wanted to do was face the elements again, but his confidence put us somewhat at ease. Soon we were outside again.

Our house was 50 yards away, dead east. I grabbed Willard, who was born and raised on the North Slope. Tiffany grabbed me and we were off, getting hammered in the face once again by the bone-chilling gale. The blinding conditions and blowing snow were horrendous. At times I couldn’t even see Willard at the end of my arm.

Within five minutes, however, we were safely in our house. Willard told us it was one of the worst storms he could remember — and he had seen many in more than 30 years of life in the Arctic. He instructed us not to leave our house for any reason until the storm ended. We didn’t have to be told twice.

After warming up and enduring our thanks, Willard — brushing aside our objections — returned to his own home.

When the door closed, Tiffany and I held each other and wept. Fear, helplessness, relief, and elation had coursed through us and, with the storm, left us, weak and spent. We had touched death. I had totally underestimated the power of nature and it had nearly cost both of us our lives.

After the Storm

I phoned the principal. Nearly 30 minutes had elapsed since we’d left the school, and all but five of those minutes were spent outside. He had called Search and Rescue to as I’d instructed, but due to the magnitude of the storm, there was no way they could go out looking for us.

It took several hours to fully regain feeling in our hands and faces. Tiffany was in great pain as her hand thawed. She suffered minor frostbite on it, as I did on my face. After a couple days the skin on Tiffany’s knuckles and around my eyes, forehead, and cheeks darkened and peeled in small, painful strips. It felt like a deep sunburn, but considerably more painful. If I had worn my goggles to school that morning, they would have shielded much of my face and improved visibility.

The storm endured for two more days, never subsiding. From the confines of our home we watched in awe, realizing we would not have survived the elements much longer. Visibility remained fewer than 10 feet and temperatures hung at 45 degrees below days beyond that. It took us the next day and a half to get over our headaches and the stinging windburn.

When the storm died out on Monday morning, crews began the laborious task of clearing the roads. The one snowdrift that cut through our path in the middle of the road — the one we had climbed up and fallen over — measured 45 feet tall.

One house had been completely buried in snow, with just the smokestack protruding, and the family inside had to be dug out with heavy equipment. Others had to dig their way out from the inside, us included. Village dogs had been buried in snow and, with their thick coats and layers of winter fat, stayed insulated well enough that most survived.

At school on Monday, our Inupiaq Language teacher and long-time Point Lay resident, Lorena Neakok, hugged us and told us how scared she had been for us. Like most villagers, Lorena had heard over the CB that we had been caught in the storm. Many people had searched for us from their windows.

Read Next: I Nearly Froze to Death When Our Argo Sank in the Middle of an Arctic River

Lorena told us of a storm a few years before when a woman tried walking next door during a similar storm. She never made it. Villagers found her frozen to death between the two houses. She had died fewer than 10 feet from a building she could not see.

Every village I visited during our seven years living on the North Slope had stories like ours. It’s a situation you can only imagine until you experience it. Though deeply shaken by the experience, it helped me better prepare for future outings in the Far North. I was reminded how valuable life is, and how swiftly it can be taken away.

For personally signed copies of Scott Haugen’s best-selling book, Hunting The Alaskan High Arctic, visit scotthaugen.com

The post My Wife and I Tried to Walk Home in an Arctic Storm. We Almost Died appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/survival/nearly-died-arctic-blizzard-alaska/