My Buddy Caught His Personal Best Bass During a Lightning Storm

This story, “Bulge on the Potomac,” appeared in the July 1954 issue of Outdoor Life.

One morning last summer Dorsey Clark and I decided to go bass fishing, though we had no great hopes of catching anything. Except that the Potomac River was running just a little cloudy instead of the dirty yellow ocher it often does, conditions couldn’t have been more discouraging. The water was low, there wasn’t a whisper of a breeze, it was steamy hot, and the sun blazed down on mirrorlike pools. Just the same, we decided to go bass fishing.

The Potomac, one of the good Eastern black-bass rivers, offers some 400 miles of fair-to-excellent fishing-mostly smallmouths upstream from Great Falls on the outskirts of Washington, D. C., and largemouths in the tidewater downstream.

Smallmouths aren’t native to the upper Potomac, but they’ve been in it a long time. Come this fall it will be just 100 years since Gen. W. W. Shriver of Wheeling, W. Va., netted a dozen or so adult fish in a tributary of the Ohio River, had them carried across the mountains in a perforated tin box suspended in the water tank of a Baltimore & Ohio locomotive, and planted them in the Potomac below Cumberland, Md. — probably the first, certainly the first recorded, stocking of smallmouths east of the Alleghenies. The plant was successful, for in 1860 Jack Shrodes, a B. & 0. conductor, caught a string of smallmouths in the river near Cumberland and gave them to Shriver.

The fish spread downstream, populating the fast-water reaches and leaving the more placid stretches to catfish and carp, and in some places to largemouths which have been stocked from time to time but never too successfully. Some of the best smallmouth water is close to Washington-the half-dozen miles of island-studded and ledge-cluttered river from Great Falls upstream to what’s left of the old dam at Seneca. There you can catch smallmouths almost any way you choose — stillfishing; casting spoons, plugs, and spinning lures; wet-fly fishing, and (once in a blue moon when every thing’s exactly right) with dry flies.

Dorsey is a plug-and-spoon enthusiast who can pinpoint any likely-looking spot of water within reach. But on the morning we decided to go out he weakened. “Better stop by at Jimmy’s and get some minnows,” he suggested some what sheepishly. “On a day like this, stillfishing’s the only way we’ll have a chance.” So we stopped at Jimmy’s and got the minnows.

Dorsey usually ties up his square-ended punt on the river bank at Violet’s Lock where, years before the old Chesapeake & Ohio Canal lock house burned down, President Grover Cleveland used to fish for bass. But because of the low water Dorsey had been docking the craft near a deep little run a mile downstream where there’s no road leading to the river.

We slithered down a steep bank, loaded our duffel into the punt, and shoved off. There was just enough water to float us through the dank tunnel under the ancient stone aqueduct that carries the canal over the mouth of the run, and out in the river there wasn’t much more. We pointed the boat’s blunt nose upstream along a narrow channel that twisted between big boulders and over dark ledges. Now and then we hit a ledge and the outboard motor tilted up, but the spring-steel shoe under the lower end of its shaft a Potomac River gadget that’s becoming popular in shallow waters elsewhere-saved the propeller.

Soon we reached a stretch where the river is more than half a mile wide, but down its middle is a long string of heavily wooded islands. They’re uninhabited, and some haven’t even got names; you often see raccoon tracks in the mud along their shores, and on one a small colony of river otters is making its last stand. We kept on going upstream for a mile, then anchored in the tail of a pool below a long riffle.

Dorsey’s never in a hurry, but when he reaches the place he wants to fish no one gets a line over quicker than he. He was making long casts into a big backwater before I’d finished setting up my spinning rig. He fished every yard: of it, but didn’t get a nibble.

I selected a small silver spoon with a strip of pork rind on it, snapped it on my line, and cast into the riffle. I got a strike the instant the spoon plopped into the water. It was a lively little smallmouth that splashed around some, but you can’t expect an epic struggle from an eight-inch bass. I quickly unhooked it and slipped it back.

I cast again to the same spot and worked the spoon down the riffle and into the pool. Nothing doing. But half a dozen tries later I connected again-this time with a six-incher. “Quit picking on the chil’n,” Dorsey chided. In summer, I’ve found, riffle smallmouths nearly always are midgets; the big boys stay deep in shadowy pools.

We worked farther upriver, fishing all the likely-looking water. I couldn’t coax a strike, but Dorsey, casting a deep running plug, hooked a fish in a rock-rimmed pocket. When he brought it alongside he gripped its lower lip between thumb and forefinger and held it up. (I’ve never seen a Potomac River regular use a landing net.) The measuring stick showed it to be barely the legal 10 inches, so Dorsey let it go.

A little after noon we came to a stretch of river called The Breaks, a series of fast runs and shallow pools which, when conditions are right, are worth wading with a fly rod. But conditions weren’t right. There was more water than we’d expected, and where it swirled around a deep pool at the foot of the lowest run it was quite muddy. We figured there must have been a hard rain somewhere up the valley and that there’d be even more water coming down in an hour or two. Maybe that would·make the bass start biting — the first few hours of a good rise of water does sometimes. We went ashore on an island and ate lunch. It was hot. Nothing moved nearby, but high overhead two big buzzards circled slowly. I noticed the sky had darkened from blue to smoky gray. The only sounds were the drone of insects and the gurgle of the current along the mudbank. It was easy to imagine we were on the edge of a tropical jungle, but not 15 miles downstream were half a million people.

“Reckon we’d better use those min nows,” Dorsey said after a while.

We shoved off in the punt, drifted a way, and anchored 50 feet above a sizable pool. We baited our minnows, clamped a couple of buckshot on the leaders, and let the current carry the rigs down into· the pool. Then we waited. And we waited some more. We’d been waiting for almost an hour when Dorsey suddenly hoisted his 200 pounds to his feet, took the cover off the bait pail, and dumped the minnows into the river. “Enough of this,” he said. “If we want to catch any bass today we’ll have to go find them.”

One reason why Dorsey catches more Potomac smallmouths than most anglers is that he knows the river almost as well as the bass do. In his mind is a picture of the river’s bottom showing ledges, pockets, and deep holes you’d never suspect existed. Each of his seemingly casual casts drops his plug in a spot where he knows a bass could very well be lying head-on to the flow. He doesn’t always hook a bass even if one’s there, but he doesn’t waste time fishing barren water.

We floated downchannel with the current, which was beginning to run faster. I again resorted to my silver spoon and pork-rind strip, and worked what looked like good water in near the islands. Dorsey, fishing his favorite bottom-bumper lure, made spot casts into the flat water midstream.

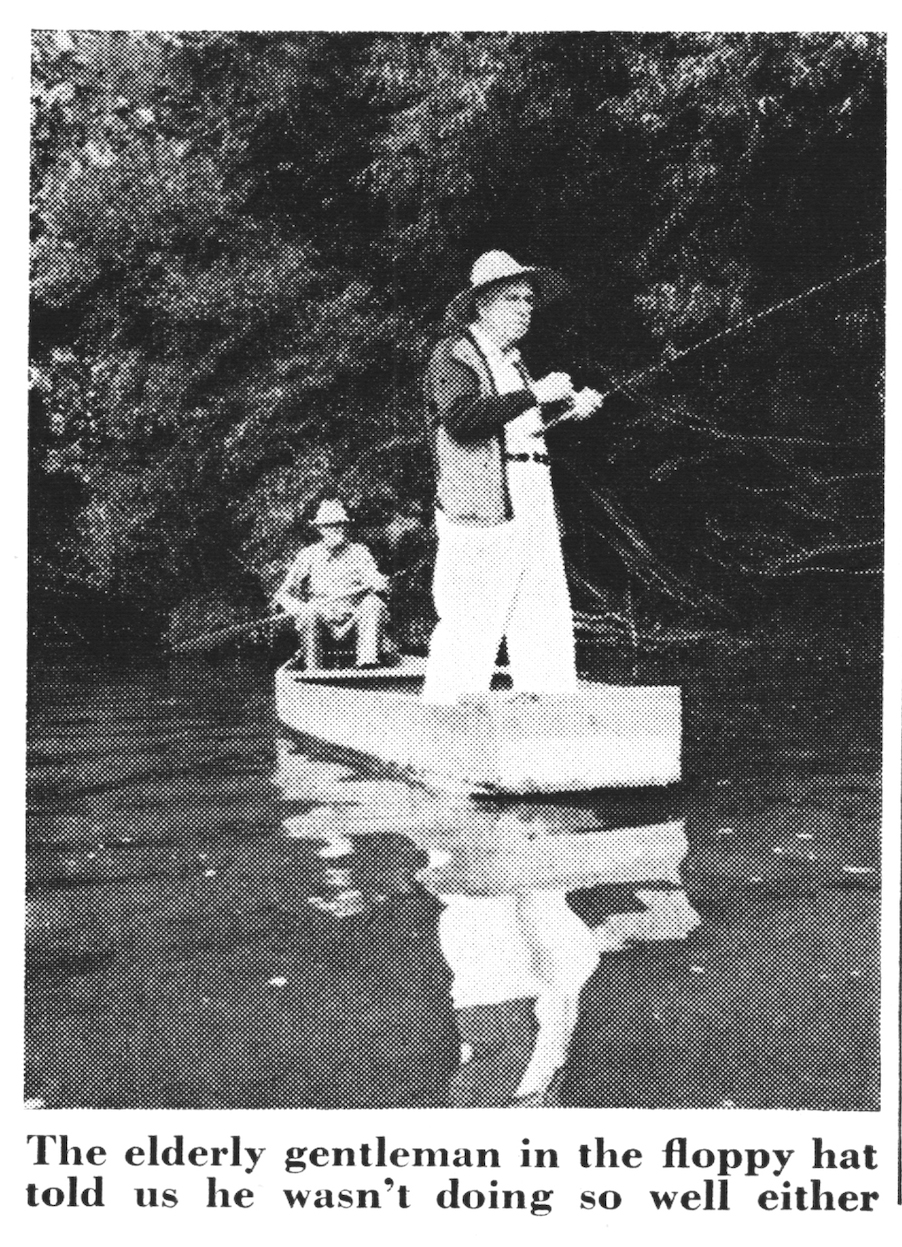

Half a mile downstream we drifted by an elderly gentleman who wore a big, floppy straw hat and was casting industriously from his punt. He told us that he wasn’t having much luck either. His was the first boat we’d seen all day. Though that particular reach of the Potomac is close to Washington, not many persons know about it, and a few dozen local fishermen have it pretty much to themselves.

When we were across from the run where we’d started fishing that morn ing I heard Dorsey grunt. “Fish bumped my bait,” he said.

He retrieved slowly, but the fish didn’t follow. He cast again, and eased the bait in. While I was watching him some vagrant current carried my spoon out of the slack water and into the channel. When I felt the pull of the current I started to reel in and got a good, solid strike. Confident the fish had hooked itself, I flipped the anti� reverse lever of my spinning reel. The bass ran across the current into slack water, and as I twisted the reel’s thumbscrew to increase the drag my rod arched sharply and the fish came out of the water.

Smallmouths don’t usually jump like bigmouths, but this one put on a good show. Although his leaps weren’t high, he made half a dozen of them and skittered across the surface in a shower of spray.

I heard Dorsey say, “I’ve got one,” but I was too busy just then to turn my head. My fish was coming upstream so quickly I couldn’t reel in fast enough to take in all the slack. He went under the boat, and kept on going for about 10 yards. It was a gallant run but it took a lot of the moxie out of him, and after he’d made one more skittering jump and a plunge to the bottom I brought him up. He was a nice small mouth-about 14 inches and an ounce or so over two pounds. While I was gloating over him Dorsey boated his fish, which was an inch shorter.

Two fish on at once made us think we’d hit the jackpot, but we hadn’t. An hour’s casting didn’t get us another strike, and in that time the river rose a couple of inches and the water rush ing over the dark ledges took on a yellow tinge. “Before long we’ll be able to walk across to Virginia on the mud,” Dorsey said. “Let’s try along the banks of the islands. The water there will stay clear for a while.”

We pulled up the anchor and put putted over an old ford much used by both Federal and Confederate cavalry during the Civil War.

“There’s a good place,” Dorsey said, and turned in toward a little bay, or what some of the old rivermen call a “nook of water,” on the shore of one of the islands.

By mid-afternoon the weather turned downright unwholesome. The brown gray overcast turned to saffron yellow, and the sun burning through it drained the river of its color and faded even the vivid green of the thickly timbered islands.

Dorsey, who spent two years of World War II navigating planes over the Burma-China hump, cocked an eye skyward and remarked he was glad he wasn’t flying. But get ting wet is the worst that’s likely to happen to you on the Potomac in a flat-bottomed punt with an outboard to drive it, so we went on fishing.

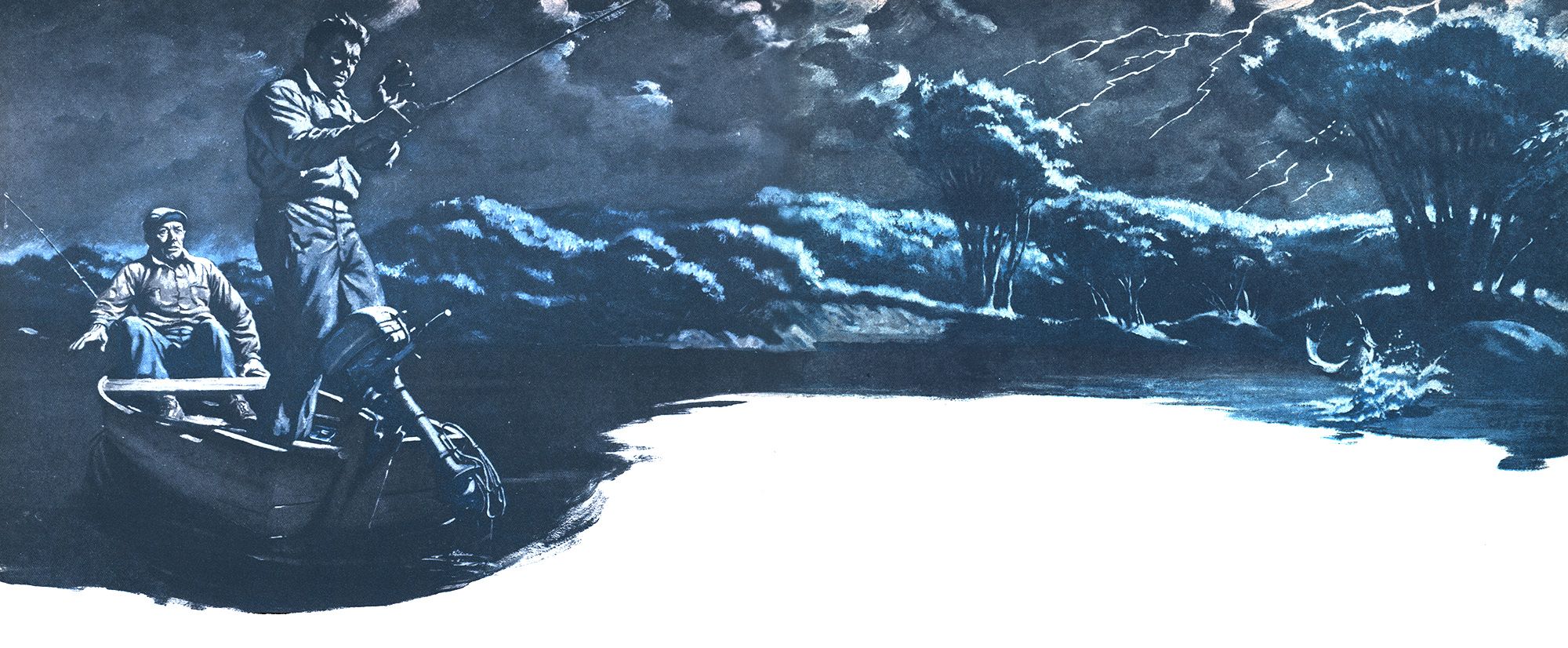

But not for long. It got dark suddenly — dark as late dusk. Up the valley lighting forked across the purple sky and we were about 50 yards off the is land when the rain hit without wind or warning. It was the closest thing to solid water I’ve ever seen come out of the sky. We grabbed our windbreakers and pulled th em on over shirts already plastered to our backs. Then, after maybe two minutes, the rain stopped.

Dorsey shook the water out of his eyes like a man who’s just come up after a dive. He pointed toward the island. “Look at that,” he cried. Bass were feeding all along shore — breaking the surface as they gobbled the insects which the downpour had washed off the trees and brush along the banks.

Without saying a word we both took off our deep-running lures and snapped on surface baits. Then we grabbed the poles and pushed the punt slantwise across the current toward a little bay. About 50 feet outside it we gently lowered the anchor.

I’d rigged my line with an inch-long yellow popper that sports a yellow hair tail; Dorsey’s choice was a larger black gurgler. We got strikes on the first cast and boated both fish — each about a foot long.

Chances are we’d have filled out our creel limits in half an hour — if we hadn’t seen something. What we saw at first wasn’t a fish, but a big bulge on the water about 20 feet from the boat. It was followed by a dimple so large it almost was a swirl, and then a little splash as part of a broad, bronze back broke the surface. It disappeared swiftly, but the fish didn’t go deep. We followed its course by the bulge as it swam steadily toward a big gray rock sticking up out of the water on one side of the entrance to the little bay.

“That’s a big one,” Dorsey said, sounding sort of out of breath. “I’ll bet his lie is just below that rock. There’s a deep hole there. If—”

It isn’t often you see unhooked small mouths jump, but all that food washing down the river must have driven them crazy. That big boy came straight up out of the water until his tail was a foot above its surface, then smacked back.

Dorsey and I looked at each other. Both of us wanted that bass, but it wouldn’t have made any sense for both of us to try for it. We were in Dorsey’s boat. That made me his guest — and he’s a Marylander. “Go ahead,” he said. “Cast to him.”

I was tempted, but, after all, Dorsey’s my friend. I knew I couldn’t argue him into taking the first shot, so I fished a quarter out of my pocket, showed it to him, and spun it in the air. “Heads,” he said. The coin plopped on my palm heads up.

Dorsey eye-measured the distance, and cast. His plug hit the water 10 feet upstream of the rock, and as the current carried it down slowly he twitched his rod tip and made the lure splash and gurgle. The plug drifted by the downstream end of the rock and approached the surface of the deep hole. Dorsey kept it splashing. If that big bass—

Just then a searing flash of lightning ripped through the sky, and a concussion jarred me all the way down to my heels. Next thing I knew my hands and arms were tingling, there was a strong smell of brimstone in the air, and I was blinking my eyes to get the blinding blue-white glare out of them.

When my sight cleared I saw Dorsey was still holding his rod, but it was drooping so its tip was inches from the water. Getting his vision back a mo merit after I did, Dorsey raised the rod and looked down at the water for his plug. It was gone.

Another bolt of lightning struck close on the island, and a split second later a terrific thunderclap tried to beat in our eardrums. Dorsey paid no attention. He thumbed his reel lightly, pushed on its click, and struck. The rod bent sharply.

“Got him,” Dorsey said. “But he’s going like hell.”

The fish kept going and the rod Jerked and quivered, but Dorsey held on. Then the rod snapped straight, and he reeled in fast. When he got the slack out the line, it was pointing down into that deep hole just downstream of the gray rock.

Then the wind hit us. It came down the valley with a roar and a groan, and was so solid you could lean against it. It clawed the mirror-smooth water into foam-capped waves, but in half a minute it blew on downriver and everything was still again.

Dorsey hadn’t even looked up. “He’s way down deep,” he said. “I’ve got to bring him up.” He began to reel in slowly while concentrating on the taut line. “Here he comes.”

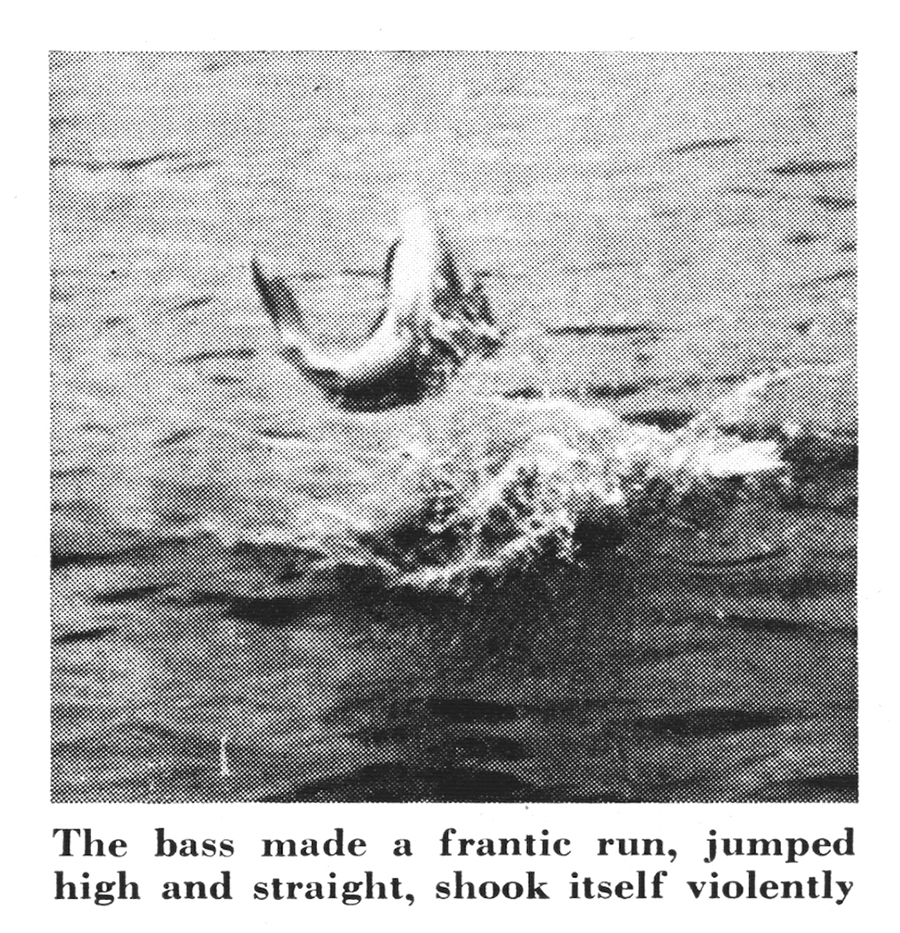

The bass rushed out of the water spangled with spray, and in the white flashes of forked lightning it looked bigger than any bass I’d ever seen. It jumped straight and high, shaking violently in its effort to throw the plug hanging from its lower lip. Then it splashed back and went off on a frantic run. Dorsey stopped it, but 20 feet from the boat the fish jumped again, flopped back with a loud splash, and zoomed upstream.

Read Next: I Lost My Favorite Bass Lake to Development. A Stranger Helped Me Find It Again

Dorsey kept the pressure on, and slowly the fish came back. When it saw the boat it started another run, but two minutes later was on its side next to the punt. Dorsey got a grip lower lip and lifted it in.

“Biggest smallmouth I ever caught,” he said. “Four pounds and a half maybe even five.”

We took a good deal of water over the bow going back across the river, but it didn’t matter. “Going fishing tomorrow?” I asked when we were over the worst of it. Dorsey shook his head. “Got to work,” he said. “Anyhow, the river will be too muddy. But it sure paid off today!”

The post My Buddy Caught His Personal Best Bass During a Lightning Storm appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/fishing/smallmouth-bass-lightning-storm/