My Buddies and I Caught 500 Wild Trout in 3 Days on an Old-Fashioned Canoe Trip

This story, “Old Fashioned Trout Trip,” appeared in the June 1964 issue of Outdoor Life.

Experience has taught me that guides know what they’re doing. The silly set-up we were in, however, made me doubt the teachings of my own experience. I looked questioningly at my guide, a Native who sported the unlikely name of St. George.

“Pechez,” he commanded, pointing to the water.

“Fish here?” I asked incredulously.

“Oui. Very good.”

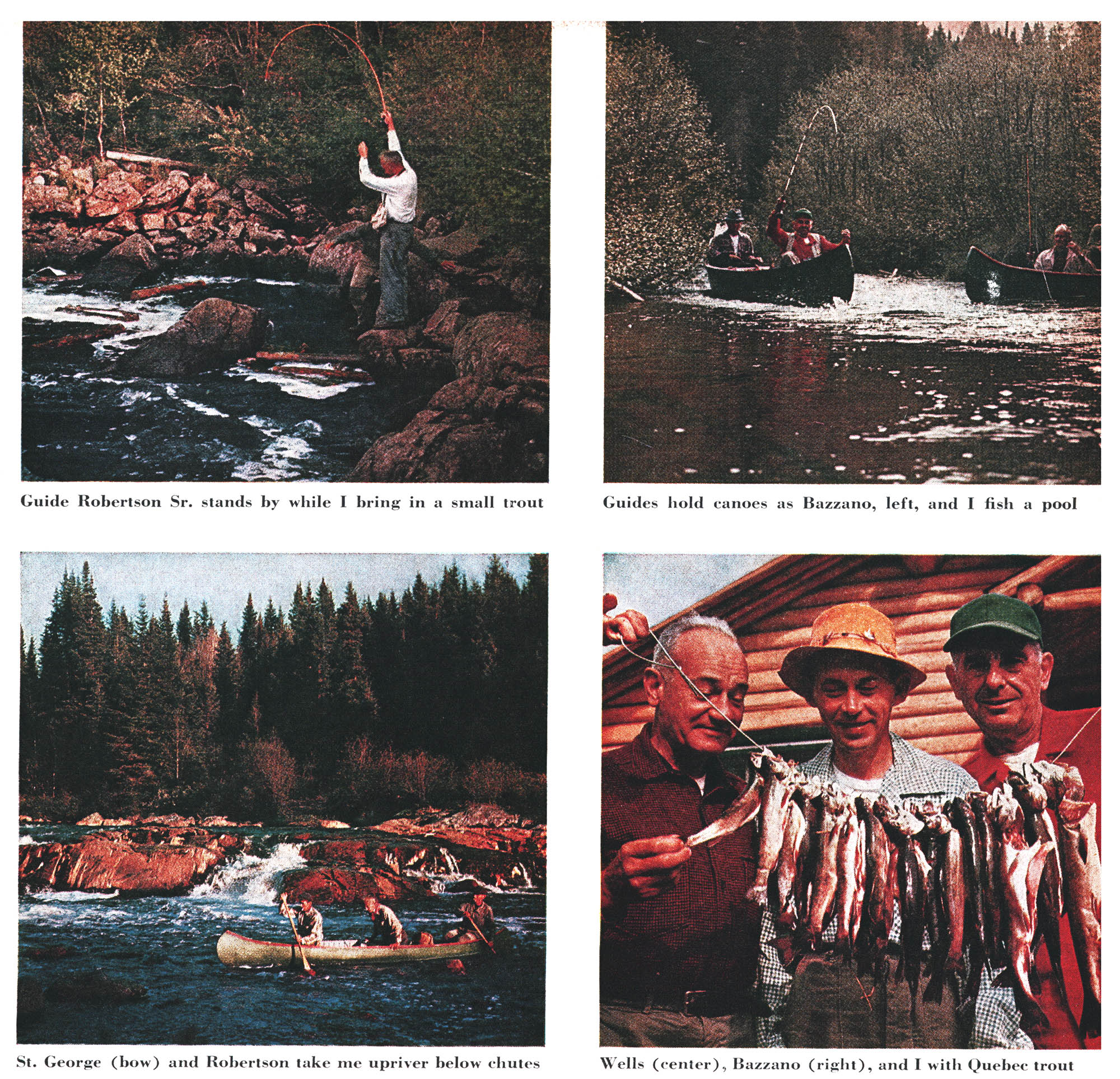

Our guides had part paddled and part lugged Wells and me perhaps a quarter of a mile up a tiny brook that was hardly a canoe-length wide. We came to a bend and a deep pool. We paddled through the pool, and at its head the guides got out of the canoes and tugged us a few yards over a gravel riffle about five inches deep. Then they swung the canoes around so that Wells and I, in the bows of our canoes, were facing the pool, which extended from a few feet in front of us to the distance of a good cast. We were parallel, and about four armslengths apart. The guides climbed back into the canoes and wedged their paddles into the gravel to hold us in position.

What there was of the water looked trouty enough. But had we travelled 700 miles for this? Out of all that vast wilderness of lake, forest, and river, our guides had chosen this little hole that we could have duplicated in scores of meadow brooks back home.

I looked at Wells. He shrugged and picked up his rod.

“Can’t see anything on the water. Guess I’ll try a small streamer,” he said, and started to look for one.

“Then it’ll be a No. 14 Ginger Variant for me,” I told him. We were soon rigged and began to work outline.

For more than 40 years I’ve been in love with a rail road. When I first knew her, she was, at least in that part of Canada, a sooty thing, scrawny, slow, and un predictable. Now she is well-upholstered, efficient, and every inch a woman of this world. And I love her. To slightly misquote the refrain from Ernest Dowson’s famous poem, “I have been faithful to thee, C.N.R., in my fashion.” Whenever I hear or see those initials, I also see trout. “They flash upon that inward eye,” as William Wordsworth put it.

I first rode the Canadian National Railroad in 1921. That was in Nova Scotia, and I was a wide-eyed kid on his way to his first north-of-the-border trout-fishing experience. I can remember all sorts of things about that ride-the clacking of wheels over lightly ballasted rails, the haunting whistle of the locomotive, the smell of fly dope in the old-fashioned coach, and the deep masculine sighs as the train sped over wooden bridges that spanned dark brooks wandering away into caverns of spruce and alder.

That was a long time ago. And here I was, on June 2, 1963, once more riding the C.N.R. into trout country. We were four middle-aged men on our way into the roadless, western area of Quebec’s Laurentide Park. We were making a sort of pilgrimage, a journey into another time as well as into another country. We were seeking wilderness trout fishing such as our forebears had known it a century ago. We were Joseph Crilley, a painter and photographer from New Hope, Pennsylvania; Sam Wells, an industrial designer and drafts man, also from New Hope; John Bazzano, an insurance counselor from Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, and myself, an editor and teacher at the University of Delaware. I also live in Kennett Square.

Only Crilley, however, had the serene confidence that we would reach our goal and still find it in its ancient glory. He had been telling us for months of a wondrous country of mountains, lakes, rivers, forests, moose, and, above all, trout. We had put down 80 percent of what he told us to the over-active imagination of an artist complicated by a virus known as squaretailitis. He had it bad. So did we. But Crilley had been there before. We hadn’t. And our ribbing had not in the least shaken his confidence.

“Another extraordinary thing about this place,” Crilley said as the train bore on through the night, “is that, remote as it is, it gets the daily newspaper. That ought to please you, professor.”

“Not me,” I disclaimed. “I want to get away from newspapers. I want trout.”

“If what you’ve been saying is true,” said Bazzano, innocently walking into the trap, “how do they get a newspaper in there? Fly it?”

“Nope,” said Crilley. “Planes aren’t allowed. They send it in by moose!”

There was an appalled silence broken at last by Wells.

“That isn’t a newspaper. That’s a moosepaper!”

“If I couldn’t make a better pun than that,” said Crilley, “I’d go to sleep.” He folded his arms, leaned back in his seat, and went to sleep.

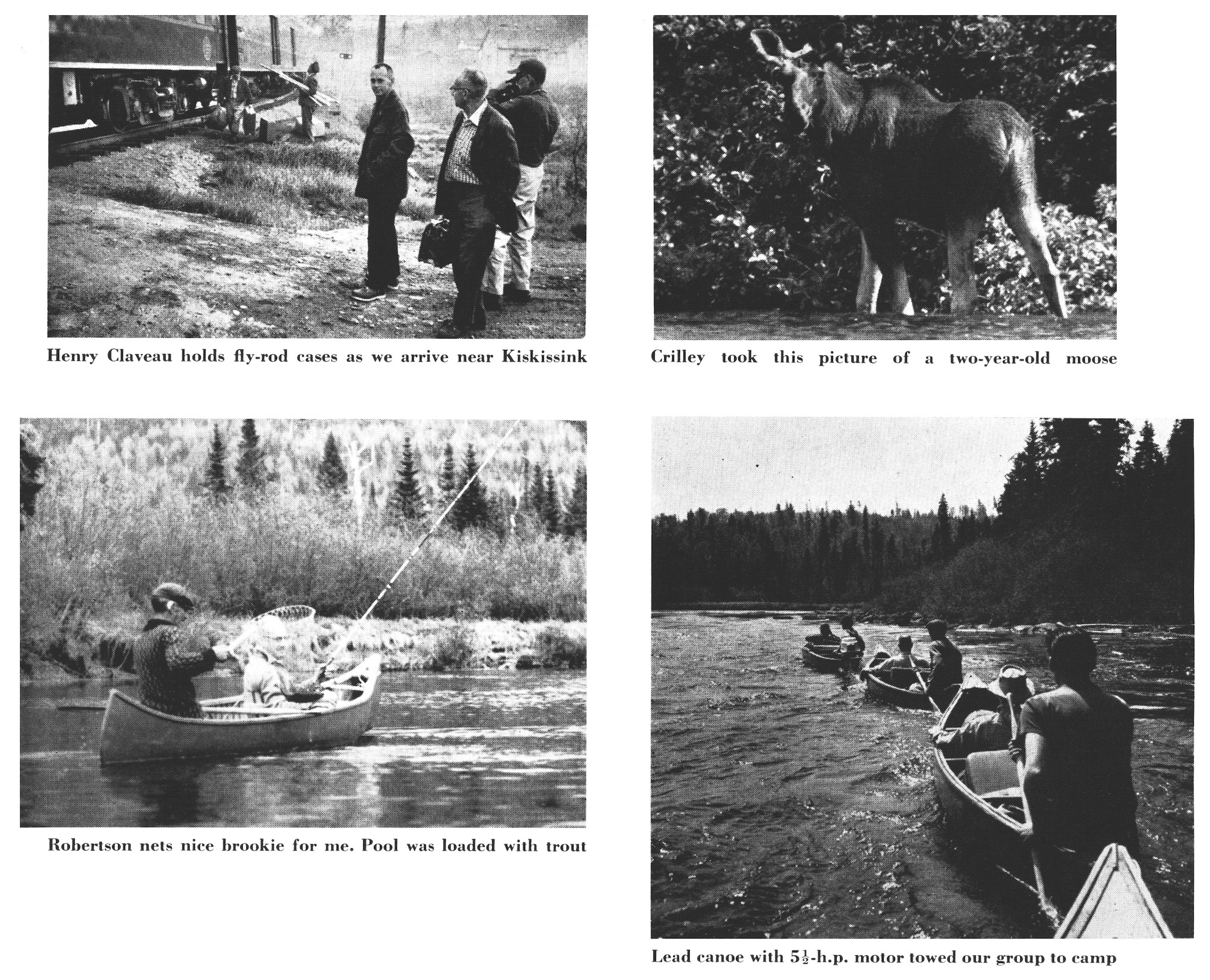

It’s a 135-mile ride from Montreal to Kiskissink, a small village about 12 miles west of the Laurentide Park boundary. We’d bought round-trip tickets, $10.35 a man, and boarded the train at 9:30 p.m. Eight hours later, the train ground to a stop and we were there.

Crilley, festooned with camera bag and an enormous 400 mm. lens that I call the bazooka, was the first to get off. Waiting impatiently behind him on the car steps, I heard him shout in his dreadful French: “Halloo, Monsieur Claveau ! Comment ça va ?”

“Very well, thank you,” replied Henry Claveau, park inspector, in perfectly good English.

“Et les peches, les poissons, les trouts?” Crilley persisted.

“Oh, the fishing’s very good, very good,” Henry replied.

It was then that Bazzano, Wells, and I began to lose some of our skepticism. Too many times questions like that had been parried with something like, “Well, they were hitting last week, but But the water’s low ( or high), and it’s pretty slow.”If the inspector admitted the fishing was good, maybe we’d come to the right place at the right time.

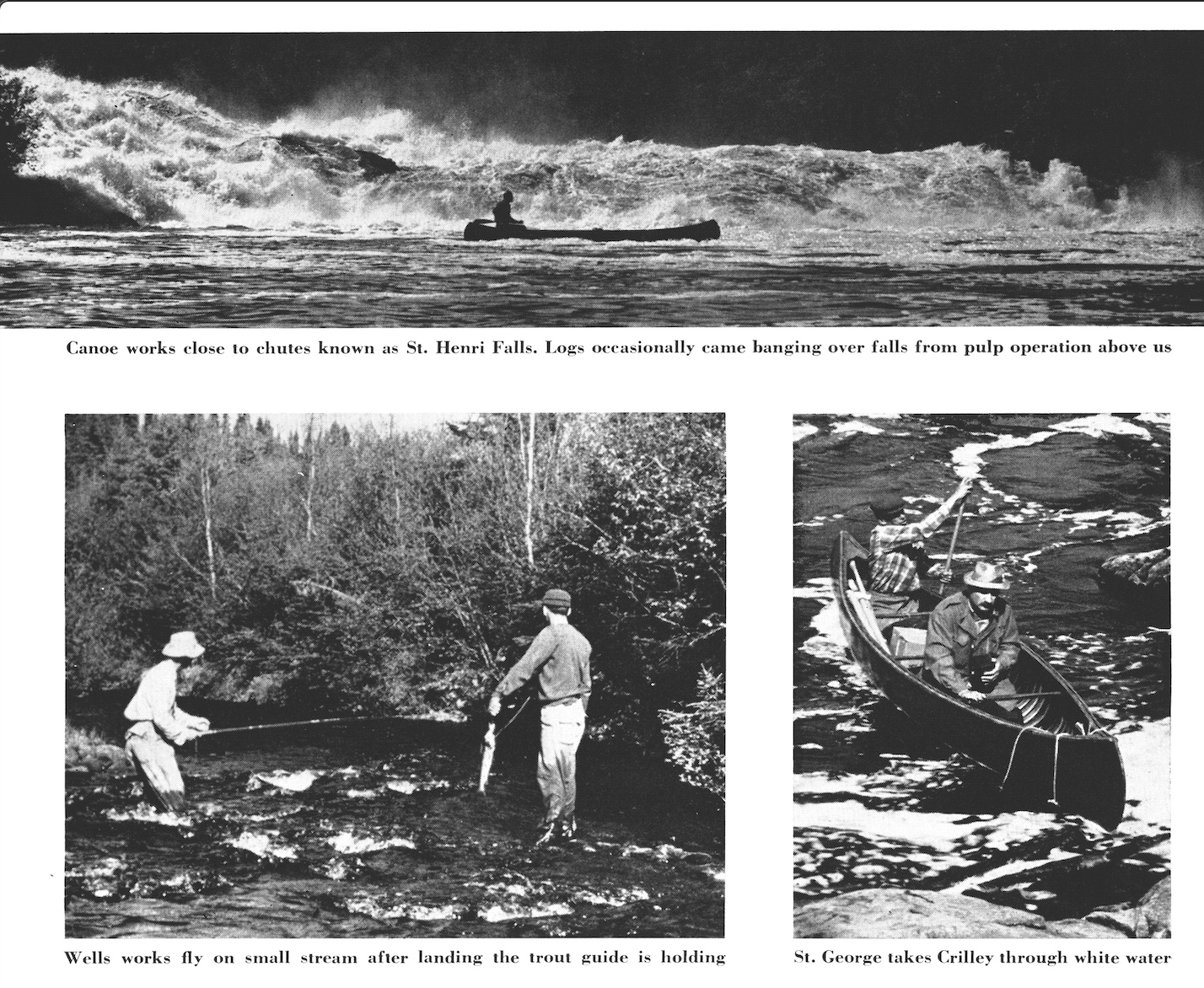

We had a good breakfast at Henry’s, then piled into his station wagon and bumped 28 miles down a lumber road to the landing across from the chutes known as St. Henri’s Falls. Across a mile or more of water, the chutes was a white gash against dark-green forest. Our four guides — St. George, Robertson, and their two sons — were at the landing, and soon we were a fourcanoe flotilla, powered by a 5½-horsepower motor, headed for the chutes.

The lakes in this area are wide places, sometimes a mile or more, in the Metabetchouan River. There is enough current in the lakes to float logs, and there was pulping activity somewhere above us. Logs occasionally came banging over the falls, but they seemed to offer no problem as we sped up the first lake after portaging around the chutes.

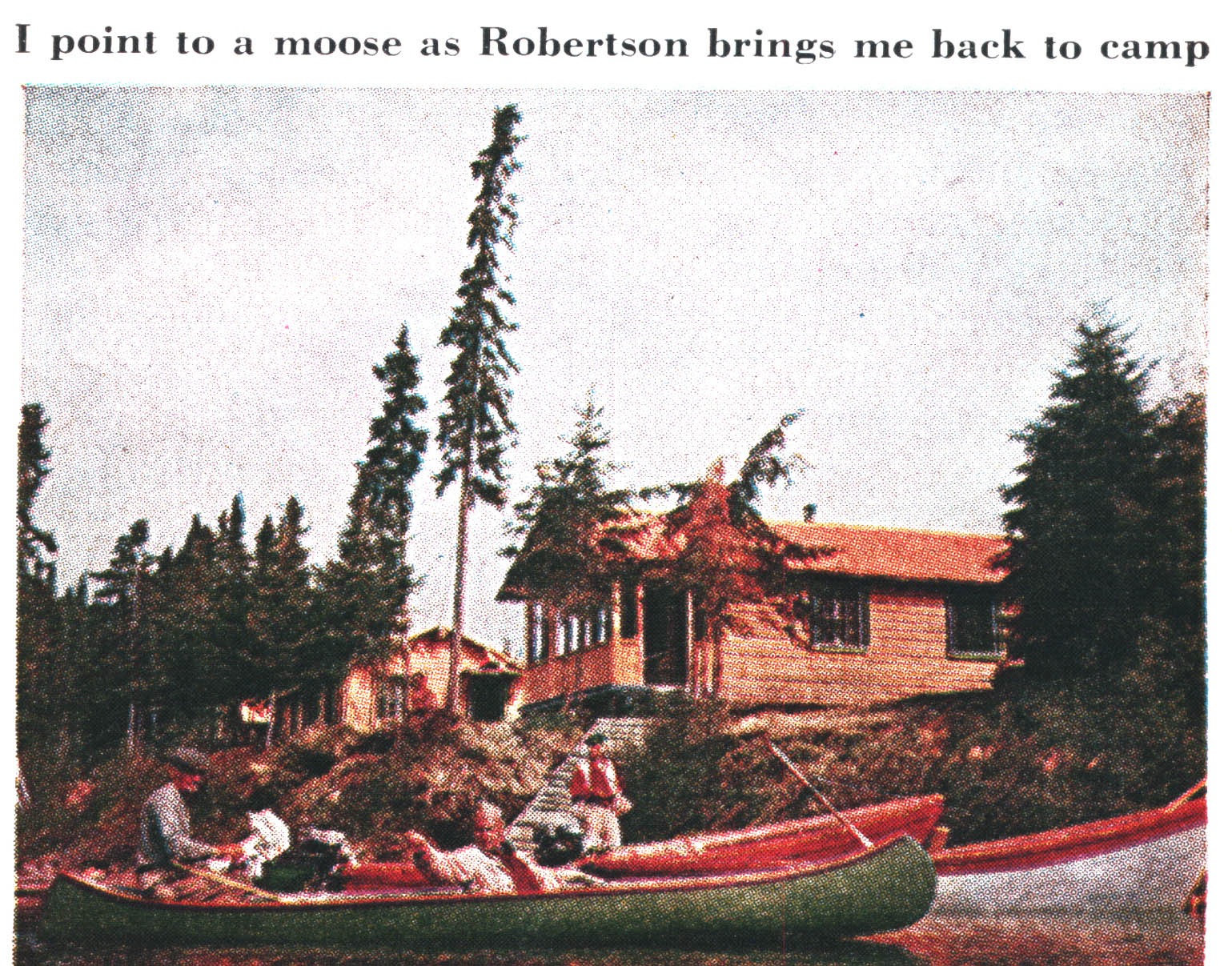

We had two more portages before we hit open water that would bring us to our camp. Just as we rounded a point I saw, perhaps two miles up the lake, a group of log buildings ideally situated on a low bluff. In bad French, I asked St. George if the cabins were our camp. My French is no better than Crilley’s, but I had to use what there was of it, since St. George spoke virtually no English.

“Ah, oui. Yes,” he replied, but I thought he sounded worried. I soon saw why. There was a brisk wind blowing from the north, and the river flows south. The wind had more effect than the current on the many logs in the lake and had backed them into a huge jam clear across the whole lake. It was a barrier several hundred yards wide, and it looked impenetrable. The freight canoe that was towing us plowed right on toward the logs, hit the first line, slowed, penetrated several canoe lengths, and stopped. Bazzano, in the bow of the freight canoe, and his guide pushed at the logs with their paddles, trying to open a pasage. They couldn’t. There was a shouted conference be tween the guides. Then, with some difficulty, we backed out of the jam, and paddled over to shore. The ground was swamp; it wouldn’t be possible to portage around the barrier. The other shore looked worse.

Only a mile uplake lay our camp, but here we were bogged down by logs. It was past noon. Precious minutes ticked away, and we burned with trout fever.

Then we heard an outboard whining from the direction of camp. Out of the distance emerged an odd-looking craft, a sort of high-bowed dory, sheathed in metal. It plowed into the log jam, slowed, almost stopped. Two strong lumbermen with spiked poles pushed and tugged at the logs, slowly opening a passage. When they finally broke through, our flotilla reformed with three of us transferring to the dory. I later learned that arrangements had been made with the lumber company for just such a contingency. Our plight had been spotted from camp and help was coming.

We inched through the jam and finally broke into open water. We were soon in our cabin, setting up our fly rods. The cabin had two bedrooms, each with two bunks. There was a well furnished living room with a stove and a sink with cold running water. The kitchen-dining-room cabin was 10 yards away, and there was an ice house as well as a guide’s cabin.

As we worked on our tackle, Crilley looked out of the door. “See what I mean?” he said, pointing across the lake. “You thought I was kidding about this place. Just look over on that meadow.”

A large moose was feeding at the water’s edge, perhaps a third of a mile away. I turned to Crilley, who was fussing with a reel.

“Aren’t you going to shoot him with the bazooka” I asked.

“No,” said Crilley. “Too far. There’ll be other chances, much closer. Besides, that’s just the newspaper moose.”

Bazzano, Wells, and I had a sudden new respect for Crilley. He had promised us we would see moose and that we would tire of catching trout. A moose had obligingly shown up. How about the trout?

After lunch, Crilley and Bazzano decided to take a nap, but Wells and I sought out our guides and pushed off. And now we were up a tiny creek working out line over a little hole. Wells’s streamer hit the water near the far end of the pool. He let it sink, then began a twitching retrieve. Meantime, I had put down my fly near the head of the pool so it would drift with the current.

Suddenly, Wells’s rod was vibrating, and I took my eye off my Ginger Vari ant to watch him play the fish. That was a mistake. I heard a splash and glanced at my fly just in time to see a foot of red-finned beauty suspended for an instant over the fly. I struck wildly … and missed. Wells boated his fish, a half-pounder. I dried my fly with a couple of false casts and put it down about the center of the pool. It lay there for a second, motionless. Then the current got it, and the fly began its drift. Again the water erupted, and again there was a trout in the air, curved over my fly. This time I did it right and was fast to my first Laurentide trout.

In the next two hours, we found that if Crilley had been guilty of any thing it was understatement, not exaggeration. Neither Wells nor I had ever had such fishing. I spent as much time drying out that Variant as I did fishing it.

Wells stayed with his streamer. Within half an hour, we had brought to boat so many trout that we lost count.

Suddenly, there was a layoff. We couldn’t coax a strike, and I figured we’d caught all the trout in the pool, and that those we’d released weren’t having any more this afternoon.

“Pas de sec,” said St. George, or something like it, which I translated to mean fish it wet. This was an easy change, since my poor fly was so troutchewed it would float only a few seconds anyway. Wells changed to a Jock Scott Mallard. Soon the trout began to hit again, and for another hour and a half we stayed right in that same spot. I don’t believe there were more than a couple of five-minute intervals when one of us didn’t have on a fish. Several times we had them on simultaneously.

These were the most active brook trout I’ve ever caught. They behaved more like rainbows than brookies. Often, they would leap several lengths out of the water over the dry fly, taking it on the down curve. When we fished wet flies they socked them with a vicious whump that immediately set our rod tips dancing. They didn’t just thrash at the surface or bore into the depths, but walked across the water exactly like rainbows.

They weren’t large fish; our biggest that afternoon was a little under a pound. But they were short and thick for their weight — prime, wild fish.

I have modest gourmet pretensions, and fish rank high on my list of good things to eat. And of all fish, the small, wild brook trout is, for me, tops on the table. We kept a couple of dozen for dinner and breakfast but figured we must have boated about 70.

When we got back to camp, we found that Crilley and Bazzano had gone fishing. Wells wanted to try out a new line and walked down to the water to lay out a few casts. I was sitting on the porch dressing the line I had used that afternoon.

Suddenly, I noticed movement at the edge of a small meadow a few hundred yards downlake. The movement resolved into a large moose ambling toward the water. When he got there, he waded out flank-deep, drank, then stood staring across at the opposite shore, perhaps three quarters of a mile away. For several minutes he stood there, then walked on out until he was swimming.

At this moment, our two guides and the lumbermen who had rescued us from the log jam came bursting out of the guides’ cabin and rushed to the bateau. They started to shove the boat out. I yelled to Wells to climb aboard, that he would have an interesting experience. He did. They spun the motor and were away. I got my binoculars and watched from shore.

They caught up with the moose well before he made the opposite shore, turned him around with the boat, then threw a rope over his head. Wells, a kind-hearted man, reached out and stroked the beast’s neck. They finally released the bull, since he seemed to be tiring. I watched him swim to shore, wade out, and then look backward at the boat before ambling into the forest. When the bateau returned, Wells had an expression on his face as though he’d seen a vision. “I touched a moose,” he said. “I actually touched a real live moose!”

When Crilley and Bazzano came in, they reported slower fishing than Wells and I had enjoyed, but they had some good ones for the larder and had released many. Furthermore, they had seen and photographed a moose, but when Wells told them his story we decided that the two photographers should not again go off together. They’d missed the picture of the trip.

We had it comparatively slow next morning, out on the big water, and discovered a northwoods disease which we identified as canoe-bottom. When incurred from other causes, the same disease is sometimes called a toothache in the rear end.

We had a trout lunch at a park shelter, since it looked like rain. But during lunch it cleared, and Crilley and ‘I decided to hike over a ridge to a chutes on a nearby river. This was a beautiful and dramatic place but somewhat frustrating. We caught plenty of halfpounders, and one or two that went a pound. But the pool below the falls was teeming with big ones, two to three-pounders. What they were feeding on, we’ll never know. For nearly four hours we threw everything at them. They would often jump clear out of the water but never strike.

Both Bazzano and Wells, however, hit the jackpot that afternoon, fishing a variety of water from the big lake to a small brook. They had another good string for the larder, but nothing over a pound.

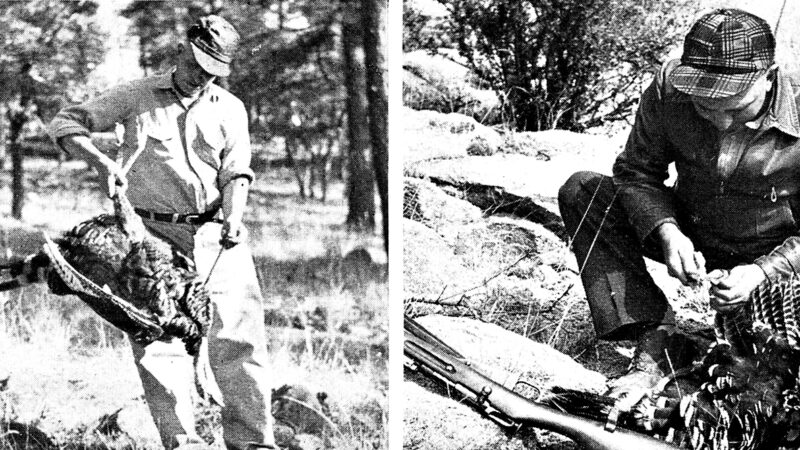

Next morning, our last, climaxed the trip. Crilley wanted pictures of the brook where Wells and I had had it so good the first afternoon. So all eight of us went there, and Wells, Bazzano, and I performed for Crilley’s cameras.

It had been good before, but now it was fantastic. There must have been literally hundreds of trout in that little pool. Suckers were spawning upstream, and the trout kept coming into the pool in schools to feed on the drifting spawn. Crilley couldn’t stand it, and, after taking some pictures, grabbed his rod and joined us. Finally, we’d had enough. Reluctant to give in to Crilley’s boast that we would get tired pulling them in, we gave our rods to the guides.

Our train was to leave Kiskissink at 11: 30 that night. After lunch, we began the trip back to St. Henri’s Falls, where we could try for some big ones in the pool below them before crossing over to the landing for the truck trip out to Kiskissink. We shot one series of rapids that we had portaged on the way up and saw two moose at the end of the last portage. Crilley shot one with the bazooka, while Bazzano shot Crilley shooting the moose.

At the falls, Crilley teased a huge trout into striking at an ancient weighted stream er with a hook he had sharpened so many times that it was woefully short. Wells also rolled a whale, but Bazzano and I caught nothing better than a few half-pounders, which we released. Though we caught none of the giant trout that are in those waters (five pounders are not rare, and six-pounders have been recorded), we had a nearly perfect experience in old-time trout fishing in a variety of waters. We were in there three days, saw seven moose, and caught about 500 trout. It was the kind of fishing our grandfathers had known in the 19th century, and we pray that our own grandsons may know something of it in the 21st. Our trip had cost us $160.35 a man, which included such items as a $5.25 nonresident three-day license, $18 a day camp rental, $12 a day for our guides, and a very expensive dinner in Montreal on our drive up.

But there are cracks beginning to appear in this picture of which we were briefly a part. For example, regulations were changed this year to permit spinning tackle. In past years, only fly fishing was permitted. Consequently, we had taken only fly-fishing tackle with us. This relaxation in the rules will probably do no harm. in itself, because normal fishing could hardly put a dent in the trout population of those beautiful waters. In fact, it would have taken us a least a week to visit all the hotspots assigned to our camp. And here, by the way, is an interesting point: when you rent a camp, your party rents not only accommodations but a huge territory to which you have exclusive rights during your stay.

What does worry me about this tackle change is that it is symptomatic of other and worse pressures. On the train going out, I met a member of the Ministry of Fish and Game on his way to a conference in Montreal. He had a de pressing tale to tell of agitation to abolish all special fishing regulations within the park, to permit airplanes, construct more access roads, and to set up more camps.

Read Next: The Best Trout Lures, Tested

One cannot blame the province for wanting to realize a good income from its forest and water resources. But let the province ponder a few other things too, which, in the long run, may well result in greater economic returns. I’ve pointed out that the four of us spent about $160 apiece on this brief trip, al most all of it within the province. We had such a wonderful time that we shall certainly be repeating this trip in years to come. So will our sons and grandsons if the province adheres to the wise regulations now in force. We pray that it does.

The post My Buddies and I Caught 500 Wild Trout in 3 Days on an Old-Fashioned Canoe Trip appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/fishing/trout-fishing-trip-canada/