Jim Carmichel’s Classic Deer Rifles

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

This story, “Classic Deer Rifles,” first appeared in the September 1997 issue of Outdoor Life.

What is classic? Mainly it’s a description we apply to just about anything we happen to like. Which is why “classic” is one of the most overused and misapplied words in the English language and also why your idea of a classic may not be the same as mine — especially when it comes to guns.

Even Webster‘s has trouble deciding what a classic is and goes to considerable length about classics in art, music and literature but says nothing about classic guns. Three of Webster‘s descriptions, however, come close to my notion of the classic deer rifle: “of the highest quality,” “having order, balance and restraint” and “meriting the highest respect.”

Read Next: 10 Classic Hunting Rifles Every Hunter Should Own

Webster‘s also says a classic may be “recognized because of great frequency,” but here I disagree. In fact, the best way to grasp the concept of a truly classic deer rifle is perhaps by understanding why some old favorites aren’t classic. This will surprise you, and please feel free to disagree, but to my mind the Model 94 Winchester lever rifle is not a classic. The fact that over 5 million of them have been sold explains why. It offered utility and reliability to thousands and then millions of hunters and woodsmen, just as the Model T Ford brought horseless transportation to the masses — but not comfort or elegance or even flair. Like the Tin Lizzie, the old M-941s an all-American favorite — but not a classic. So what is?

Consider the Model 64 lever rifle. When introduced back in 193 3, the slick-working M-64 was advertised as the “Deer Rifle” (the M-94 had been promoted as an all-purpose tool), because the marketing people at Winchester realized that a new kind of deer hunter and new styles of deer hunting were emerging. Hunting was evolving from a food-gathering necessity into a contemplative sport, and a hunter could come home from the hill empty-handed yet fulfilled. Time spent in the company of a good rifle was its own reward.

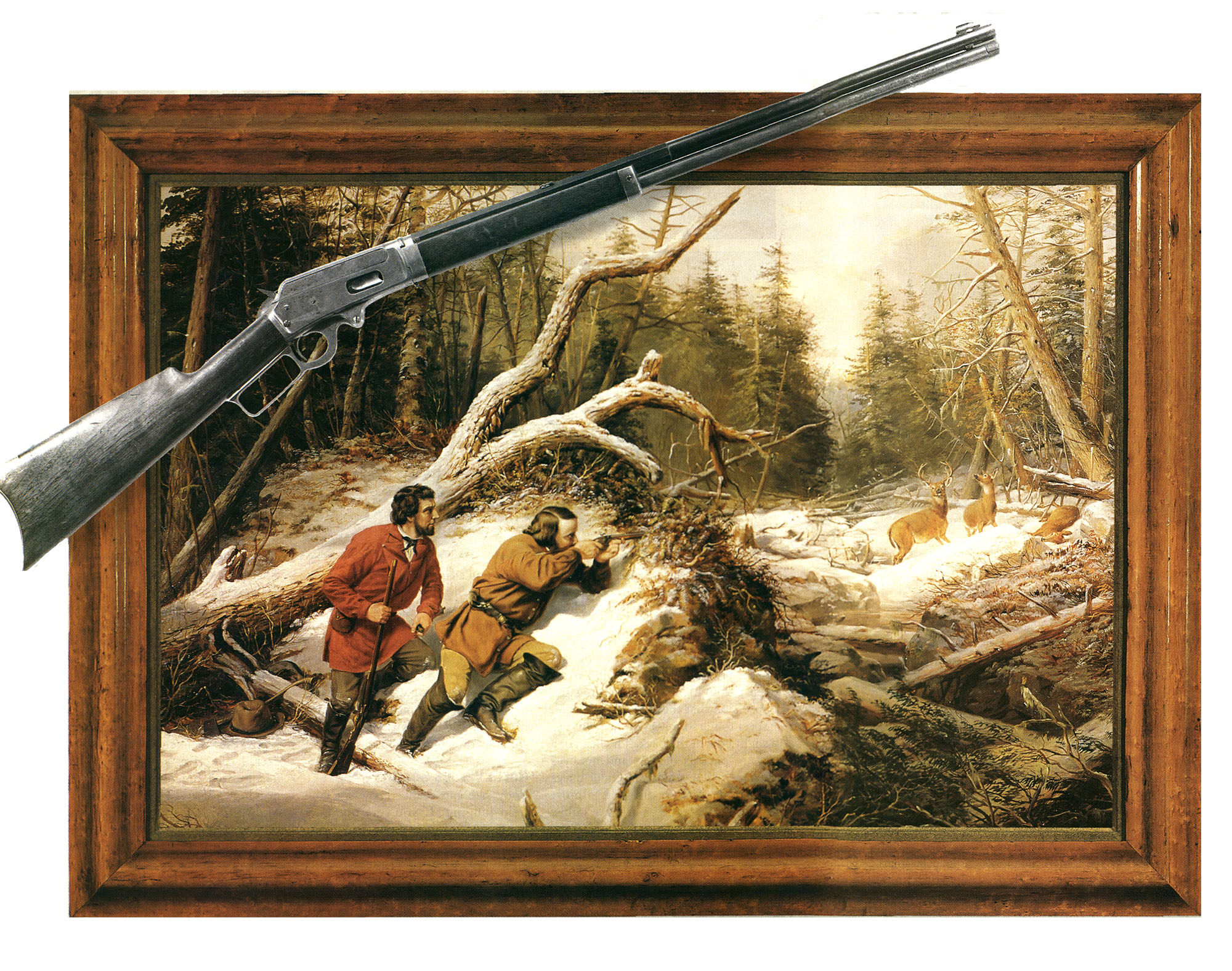

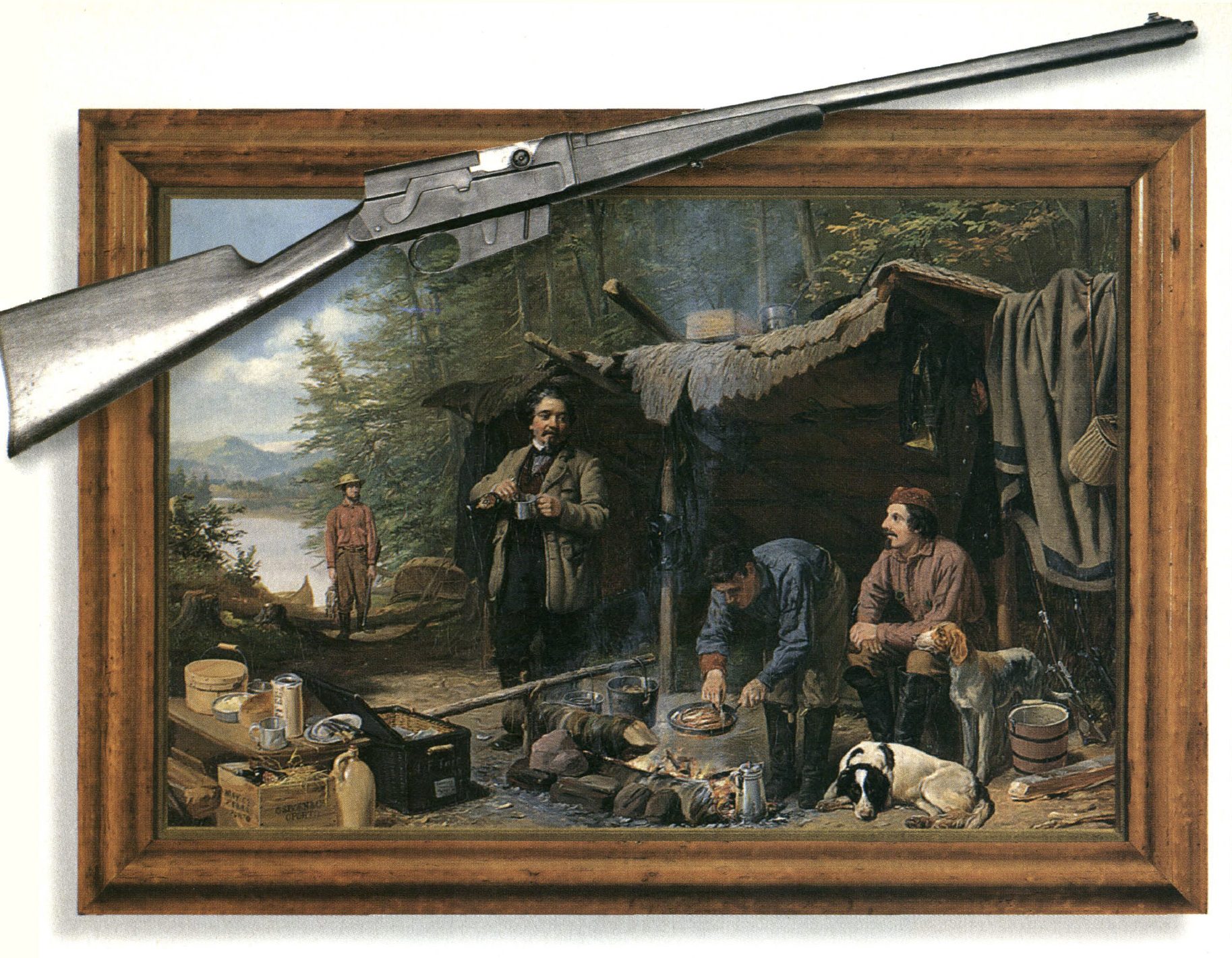

“Still Hunting on the First Snow, A Second Shot,” by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, courtesy The Adirondack Museum / Outdoor Life

Many gun experts will try to tell you that the Model 64 is nothing but an M-94 with longer barrels (20- or 24-inch) and a pistol-grip stock. In truth, most action parts of the M-64 and M-94 are interchangeable, but the real differences are more than cosmetic. The action of the M-64 was hand-smoothed so that the operation was slicker than the M-94 and the trigger was made crisper and lighter. Winchester even targeted the Model 64 for different brands of ammo. These features explain why the Model 64 sold for $46.95 back when the Model· 94 was priced at only $30. If you wanted a checkered stock it cost almost another $10 bucks, which was serious money in Depression times.

Most M-64s are in the hands of collectors these days (only about 67,000 were ever made). And if you run across one it will probably be in pretty good shape, because the type of hunter who bought a 64 tended to appreciate good quality and took good care of his equipment. When you work the lever of the 64 you’d better understand the meaning of “classic” — when the action opens you can almost smell the campfire smoke from a time and place long ago and far away. A time and place that exists only in our longings and, perhaps, is better to long for than to have.

Classic deer rifles are like fine antique fly rods (or wood-shafted golf clubs) that are classics not just because they are old and were made by patient craftsmen, but because they evoke an era when streams were uncrowded and flies were cast by Gentlemen, not logo-stamped yuppies racing frantically from craze to craze crying, “Been there, done that.”

I’d never seen a rifle like it before but its lean, stylish profile imprinted itself so indelibly on my memory that, years later, when I opened my first-ever copy of a Shooter’s Bible, I recognized it instantly.

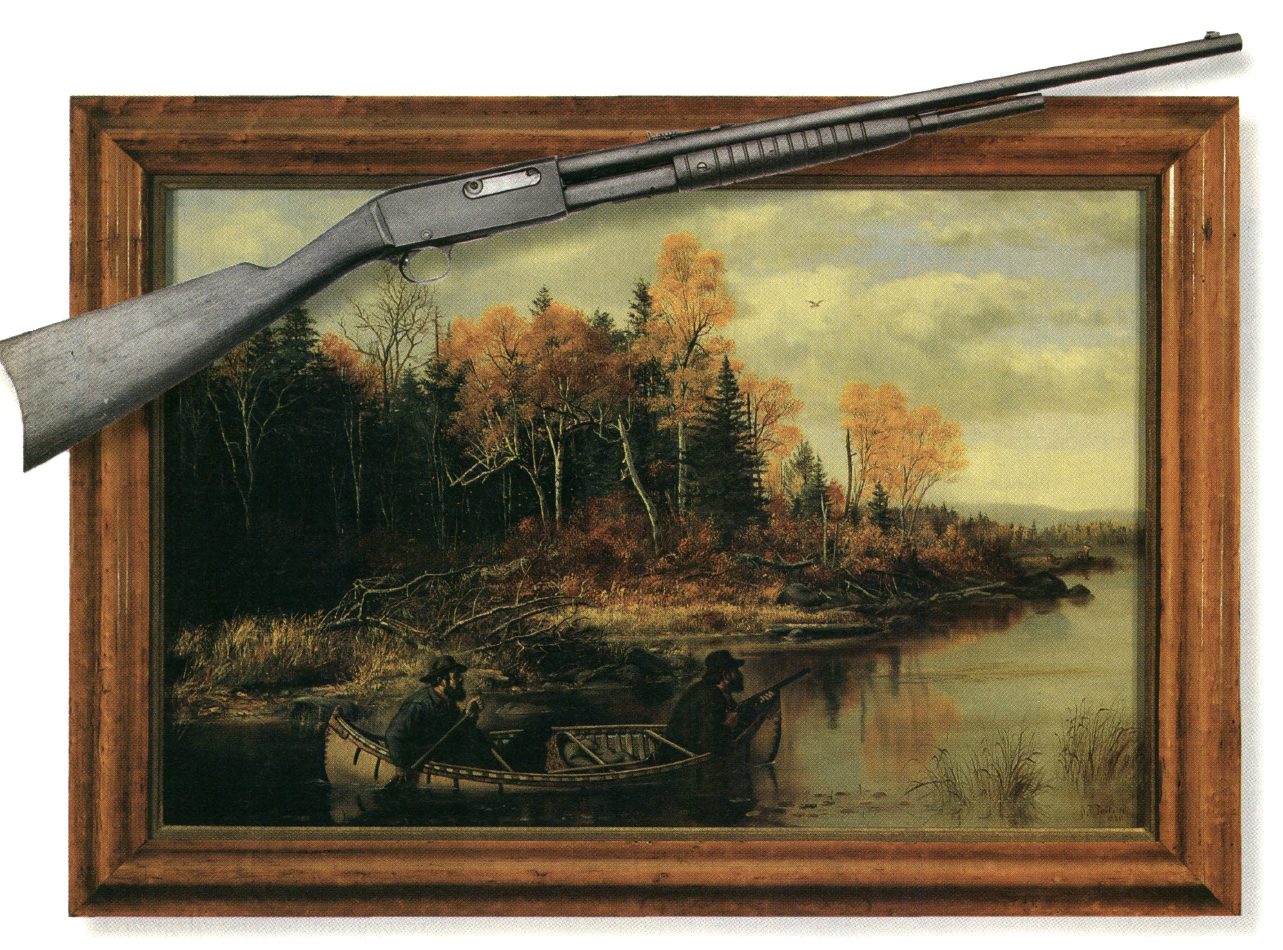

Webster’s also defines a classic as a “form or system felt to be authentic, authoritative or time-tested in comparison with later or more radical forms deriving from it.” Take a look at Remington’s Model 14 (1912-1935) and M-141 (1936-1950) pump-action rifles, and its M-8 (1906-1936) and M-81 (1936-1950) autoloaders and you’ll see almost perfect examples of Webster‘s description. All were forerunners of today’s popular autoloading and pump-action deer rifles and were also classics of form and workmanship. The M-141 had simple but elegant line’s that, like a Coco Chanel suit, remain unequaled by modern designs.

The Models 8 and 81 lack the trim lines of Remington’s pump rifle and, in fact, were — and are — sometimes mistaken for an autoloading shotgun because of the distinctive humpbacked receiver profile (yes, it was designed by John Browning) and shotgun-size barrel that is actually a barrel within a plump tube. Despite its rather unrifle-like profile, the Model 8-and its successor, the M-81-was a reliable performer and the first really successful autoloader in the deer camp.

Until 1950, when Remington made a major changeover in its manufacturing techniques and philosophies, its sporting arms were characterized by often complex designs and an extraordinary amount of hand-fitting. The trigger mechanisms of the pump and autoloading series, for example, were almost as complex as a Swiss watch, yet so perfectly fitted that they seldom failed. The rust-bluing technique used by Remington in those days was slow and expensive (requiring a number of days), but one of the most beautiful and durable ever applied to gunmetal. This is why we often see Remingtons from that era with their metal still glowing with a rich, new-looking blue.

Initially, the pumps and autoloaders both came in .30, .32 and .35 Remington calibers and, like the rifles, these cartridges are deer-hunting classics even though only the . 3 5 Remington is still manufactured. All three had rimless cases so they would function smoothly without their rims snagging on each other, and the .30 and .32 Remingtons can be called rimless versions of the .30/30 and .32 WCF because their ballistics are virtually identical.

Classic deer rifles have an attitude that is hard to define, yet unmistakable, like a work of art you know is great even when you don’t know the artist, or four unforgettable notes from a classical symphony so perfectly timed and balanced that they seem to have sprung from nature itself.

When I was a small boy it was the custom in rural communities for families to go visiting on Sunday afternoons. I dreaded those occasions because I was expected to sit motionless for hours while clad in an itchy wool suit and endure excruciatingly dull grown-up conversation. One exception, however, was our visits to a kind old Gentleman who always let me hold a Krag rifle that he said was issued to him during the Spanish-American war. His name and face are long forgotten, but sharply engraved in my memory is a framed photograph that hung in his parlor.

The picture, which probably dated from the 1920s, was of a deer camp with a canvas tent and a meat pole from which hung four nicely antlered bucks. Posing with the deer were four hunters, three of whom wore somber expressions, drooping mustaches, canvas coats over the vests and neckties that hunters customarily wore in those days, and flare-legged hunting pants tucked into high-laced boots. The fourth hunter in the picture was outfitted in a bulky turtleneck sweater and a stub-billed cap pulled low over his eyes. My imagination insisted that he was a seafaring man, the captain of a sailing ship probably. But the most arresting part of his bold presence was the majestically elegant rifle he held before him like a crusader’s broadsword. That rifle had attitude!

I’d never seen a rifle like it before and had no idea what make or model it could be, but its lean, stylish profile imprinted itself so indelibly on my memory that two or three years later, when I opened my first-ever copy of a Shooter’s Bible, I recognized it instantly. It was a Savage Model 99!

The Savage 99 in the picture was unmistakably the “F” model, with a straight-grip stock and rapier-like barrel. I’ll bet it was also chambered for the .250 Savage, which, like the Model 99, is also a deer-hunting classic. Even without its thoroughbred grace and style, the Model 99 Savage would still be a classic deer rifle by dint of mechanical innovations that make it one of the all-time classics of American firearms design.

Marlin, always seeking ways to escape Winchester’s big shadow, often did so by taking the high road, and nowhere was this more evident than with its Model 93 lever rifle. Designed by legendary marksman and firearms inventor L.L. Hepburn, the Model 93 came in carbine and rifle versions, but to my mind it’s the longer-barreled “rifle” version that is the deer-hunting classic. Though, in fact, the optional barrel lengths of the M-93 (up to 3 2 inches) were sometimes too much of a good thing.

With its lever and external hammer, the Marlin could be mistaken for a Winchester, but if you look close you’ll see how different they really are. Unlike most of Winchester’s lever rifles, which opened and ejected at the top of the receiver, the Marlin had a solid top and ejected through a side port. With the action closed, the Marlin’s receiver was beautifully smooth and virtually dustproof, a credit to Hepburn’s mechanical genius and sense of aesthetics.

The Marlin M-93 had a special appeal for deer hunters who had refined tastes and wanted rifles with better fit and finish than ordinary hunting fare. Apparently they were able and willing to pay for it because an unusually high percentage of 93s were ordered with engraving, telescopic sights (yes, even then), fancy checkered wood and pistol- grip stocks with the grip ending in a distinctive “S” curve. All of which explain why Marlin 93s are so eagerly sought by collectors, especially the Take-Down versions with long barrels that are half-round and half-octagonal.

The Model 93 was offered in .32/40 and .38/5 5 calibers, which were popular target and hunting cartridges of that low-velocity era, and the faster-stepping .25/36 Marlin, .30/30 WCF and .32 Special. Some Take-Down rifles were even ordered with extra barrels in different calibers, a rarity that causes Marlin collectors to get rather giddy.

So are there any latter-day American classic deer rifles? There are probably plenty of nominations for Winchester’s Model 70 bolt rifle as it was made before 1964. The real classics, however, were the M-70s made before WWII. Compare the feel and finish of the prewar rifles, especially the wonderful bluing that was done back then, and you’ll see what I mean. Some purists may also claim that only the rare “carbine” -length Model 7 Os should be considered classic deer rifles, especially those in classic deer calibers such as .35 Remington. I don’t disagree, but I’ll add Remington’s Models 30A and 30R bolt rifles to the list.

Read Next: The Best Hunting Rifles of 2024, Tested and Reviewed

Chances are you’ve never seen or even heard of some of the deer rifles listed here and wonder how they can be considered classics if they are so scarce and seldom seen. One reason they aren’t found even on dealer’s used-gun racks is because they are much sought after and many of them are tucked away in private collections or on display at places like the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyo. After all, scarcity is a hallmark of any classic and, as with great art, there’s never enough to go around.

Classic Firearm Museums

- The Adirondack Museum, Blue Mountain Lake, NY

- Buffalo Bill Historical Center of the West (Cody Firearms Museum), Cody, WY

- NRA Museum, Fairfax, VA

This story, “Classic Deer Rifles,” first appeared in the September 1997 issue of Outdoor Life.

The post Jim Carmichel’s Classic Deer Rifles appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/guns/classic-deer-rifles/