I Was Trapped on a Cliff, Staring Down a Charging Grizzly

This story, “The Lookout Grizzly,” appeared in the October 1971 issue of Outdoor Life.

My first head-on encounter with a bear in the Canadian North was more amusing than dangerous. At least it was amusing to my companion Arthur Brindle, an engineer for a Vancouver mining company who was posted at Telegraph Creek, British Columbia. Telegraph Creek was the end of Stikine River travel, and in 1923 I had a job there with the Hudson’s Bay Company.

I was a cheechako, or greenhorn, but Arthur had learned of my desire to explore the deep wilderness. He invited me to join him on a backpack trip to Dease Lake for the purpose of exploring mineral formations that he had observed on previous excursions into the Cassiar mining district.

It was August when we started over the packhorse trail to Dease Lake, each loaded down with a 60-pound backpack. For the first few miles the trail seemed to be all uphill. Then we entered the coolness of spruce forests and, coming over the brow of a hill, reached the seven-mile lookout. The steep walls of the Stikine canyon dropped sharply below us, revealing a boiling, twisting, narrow river. The view explained why all river travel stopped at Telegraph Creek and why the hay ranch we saw the next morning was our last sight of any form of civilization until we stood on the same spot again in late fall.

The second night we made camp at Caribou Camp, about halfway to Dease Lake. While Arthur got the campfire going I went to the creek to fill water pails. Near the creek I noticed many large raspberry bushes loaded with fruit, so I went back to get a pailful for supper.

Related: The Best Bear Defense Handguns

I had the pail half full and was picking upward on a particularly large bush when, as my head came above the top of the bush, the head of a large black bear came up the other side, not three feet from me. For a stunned five seconds we stared straight into each other’s eyes.

Arthur says he saw the whole thing from the campfire. He doesn’t know which of us was the more surprised, or scared, the black bear or me, but we both dropped immediately and took off at unprecedented speed in opposite directions, me for camp and the bear for the tall timber.

All that day at unexpected moments Arthur burst out laughing as he recalled the sight. Humorous for him, I can understand, but hair-raising for me. Still, it was nothing compared with my second encounter — this time with a grizzly bear — in the fall of that same year, 1923.

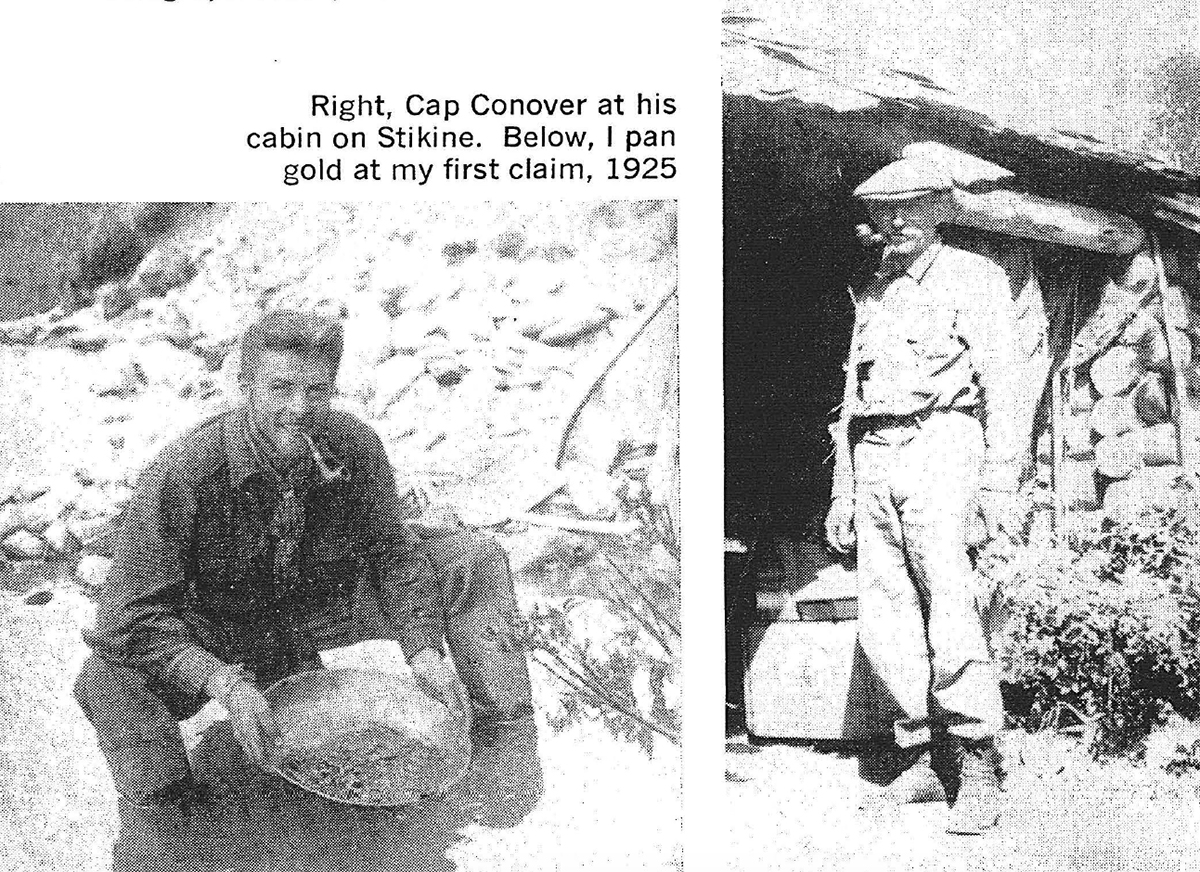

That was the year I came out of England as a 23-year-old greenhorn to strike out on my own in the Canadian North. I was born in Surrey County, near the village of Albury, the seventh son of a British government mining engineer, himself a seventh son. World War I claimed my brothers. I had joined up while underage and served two years. Upon my release I took a cram course in mining under a private tutor. I had read the books of Jack London and the poems of Robert W. Service, and I knew where I wanted to go.

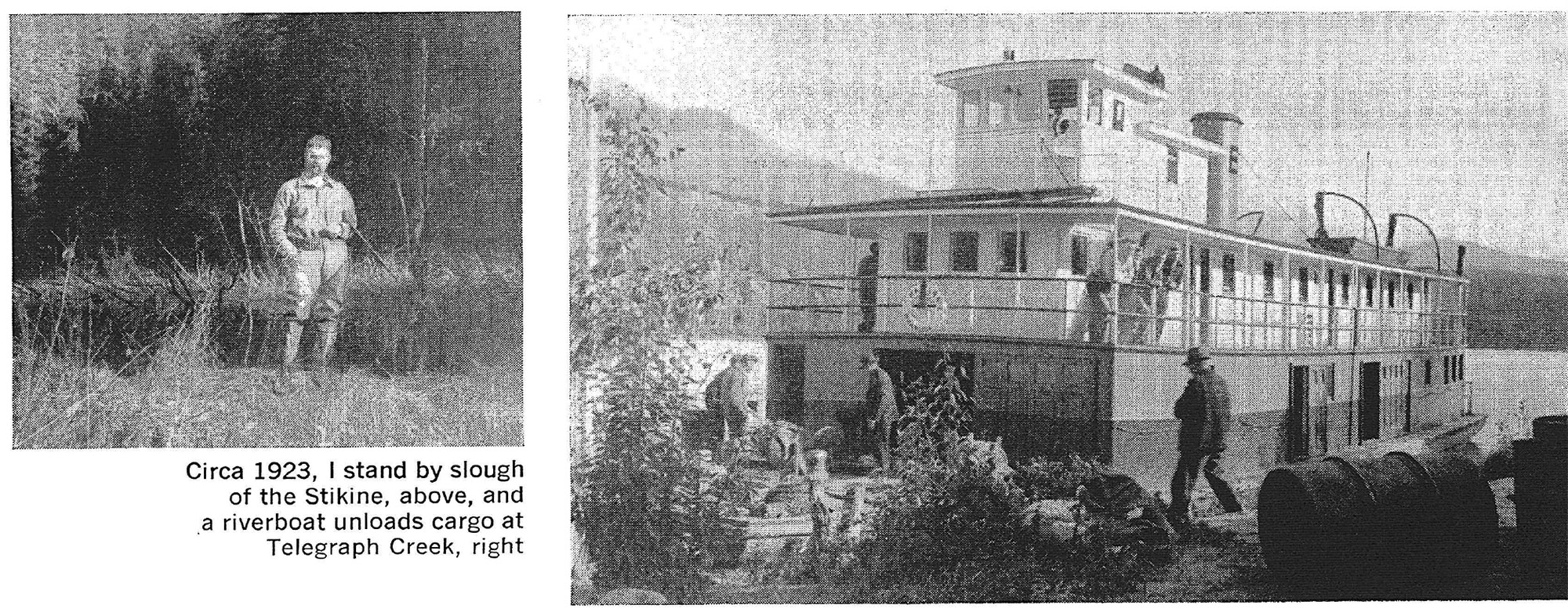

That’s why in the spring of 1923 I was aboard the Canadian Pacific steamship Alice as she left Vancouver and plodded up the coast of British Columbia via the Inside Passage, bound for the town of Wrangell in southeastern Alaska.

Wrangell Island lies at the mouth of the Stikine River, and the town is the point of departure for the river service to Telegraph Creek, 165 miles upstream. In those days the rivers were the roads of the North, and the weekly boats, powered by twin diesels, made the trip in three days. The return downriver took only 10 hours.

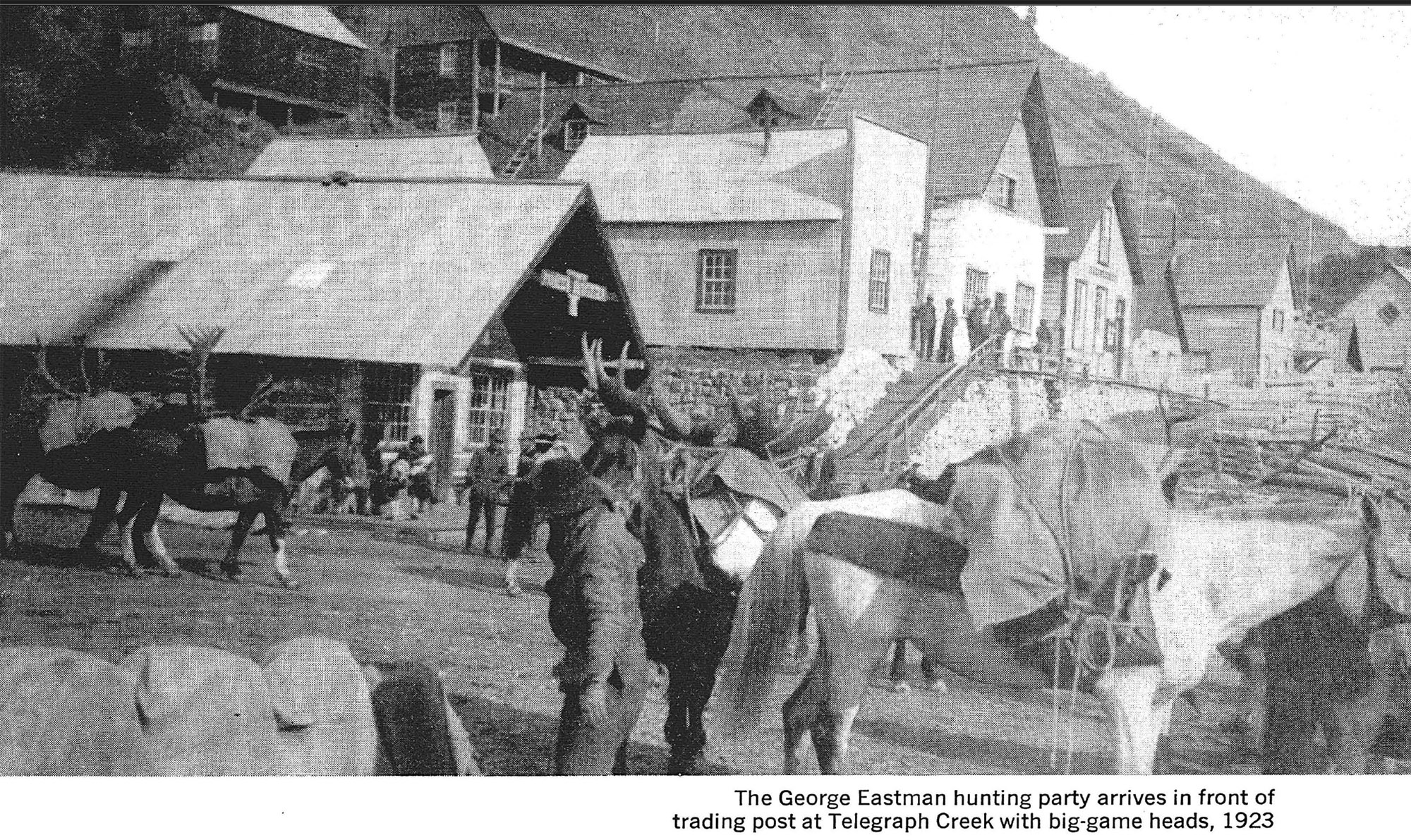

Many were the interesting events on that trip, but most important for this story was my meeting with Captain Conover, an old-time trapper who came aboard at the mouth of the Clearwater River and rode with us to The George Eastman hunting party arrives in front of trading post at Telegraph Creek with big-game heads, 1923 Telegraph Creek. The town got its name many years earlier when the Western Union telegraph line crossed the Stikine at that point. It comprised some 200 Indians and 20 white residents, and it was the jumping-off place for prospectors searching for riches in the great Cassiar mining district and for hunters seeking trophies of moose, woodland caribou, goat, Stone sheep, and black and grizzly bear. Packhorse trails led off in every direction.

At that time trophy hunting was strictly a sport for the very wealthy. Outfitters booked hunts for 30 or 40 days and sent the hunters out with a full staff of Indian guides, cooks, and wranglers. At a later date I was to visit one evening at the camp of George Eastman, the Kodak king, and his party. They traveled comfortably and leisurely, often camping for several days in one place. Eastman welcomed us and told us how he would be delighted to hear any news of a silver discovery if we made one. I learned later that even at that time his business was one of the largest consumers of silver in the world.

But to get back to my first introduction to Telegraph Creek, I reported to Mr. John Boyd, the factor (or chief trader), and I was launched on a five-year apprenticeship, or more exactly, a most eventful 40 years of exploring the uttermost corners of the continent’s northern wilderness.

The foretaste was my prospecting adventure with Arthur Brindle that I touched upon at the outset. Shortly after our return to Telegraph Creek in the fall we set out again, this time downriver some 40 miles, a trip quickly covered by boat. On the fourth day, when we had finished the task, we were visited by Captain Conover, who invited me to join him on a duck hunt. It would be three days before the Stikine riverboat stopped at the Clearwater to take us back to Telegraph Creek, so I gladly accepted.

Cap Conover was an old-timer, having come from Wisconsin 20 years before to settle into a life of trapping on the river. He spoke of his trapline as if it were a fur farm. He was familiar with every pair of animals on his line and knew their habits as most people know their children. He trapped just so many, always leaving the breeders behind, so that he harvested fur as a farmer harvests wheat.

He was a small man, standing perhaps five feet seven, but was tanned and gnarled like a walnut, his slender frame moving with the typical grace of the mountain dweller. We followed the trail along the riverbank to where he had tied his canoe and then paddled across to his cabin.

Huge V’s of high-flying geese honked as they winged southward over our heads, while the raw wind of late September scattered leaves of gold and yellow and red over the moss-covered ground around us. We pulled the latchstring and entered the little cabin, where we collected the things needed for the day’s hunt. Then, packing our 12 gauge shotguns and a lunch into the canoe, we paddled across the heavy-flowing river into the entrance of Big Slough.

The slough left the river five miles upstream, cutting a wide arc around the willow flats and then joining the river again opposite Old Cap’s cabin. The outer side of the slough made a cutbank against slides of tumbled lava, which in turn gave way to sheer walls rising as high as 500 feet above the valley floor. The lava had spewed out from a distant volcano, leaving a large, almost flat area from the foot of the mountains to the river. Over this flat, small lakes and swampy areas had formed through the ages, leaving the higher ridges between the lakes covered with timber. It made ideal feeding grounds for the thousands of ducks that came over on their southbound migration.

Our paddles dipped in unison as we slid easily upstream against the slack current of the slough. The beauty of fall in this Far North country seemed to concentrate its glories in this quiet back slough. The brilliant reds and gold of the willows and poplars and the bright yellows and pale greens of frostbitten underbrush stood out against the backdrop of the mountain slopes, which were clad in the darker green of spruce and pine and topped with a fall of snow from the last few nights. The keen scent of the fall breeze with its hint of snow now swept down the valley and stung our faces.

Two miles upstream Old Cap pointed to a high point of lava jutting out almost over the water.

“That’s my lookout,” he informed me. “From up there I can see over all of these flats and pick out a moose feeding a mile away. Makes it easier to haul out the meat from down here instead of packing it all over those hills.”

We tied up at a big cottonwood tree a little farther upstream, where a trail came to the water’s edge. Shouldering our light packsacks that contained our lunches, we climbed up the winding steep trail, shotguns in hand, for almost a mile before coming out onto the hummocky flats above. Little creeks meandered from lake to lake and through patches of lush grassy meadows and swamps, while the trail followed the higher ground covered with spruce. Moose trails crisscrossed everywhere, the tracks showing where cows and their calves had been feeding on the buds and smaller shoots of the heavy willow growth and where in places they had walked out into the lakes and all but submerged, leaving only their heads out of water, to get away from mosquitoes and flies during the summer.

“Hey, Cap,” I called out at a bend in the trail, “look at these bear tracks. They sure look awful fresh to me.” Old Cap took a casual glance at the big sign on the trail, reading it quickly but, from his long experience, noticing every detail.

“Yes,” he admitted, “it’s fresh all right. Maybe we scared him as we came along. Mostly, though, these grizzlies won’t bother anyone this time of year. They’ve been fattening up on salmon runs these last two months, and they’re fat and lazy by now.”

I thought about his comments for a few minutes but nevertheless decided that I’d feel a lot easier if I had my big .30/06 rifle along.

This was the end of my first summer in the Far Northland, remember. Except for the few months just past I was about as green as a young man could be. I had always carried a heavy rifle with me, more for safety than for hunting. I lived almost exclusively on small game-rabbits and grouse and ducks and I could get such game with a .22; or else I caught the fish that were plentiful in every creek.

My thoughts were brought quickly back to the trail and Old Cap as we came to the edge of a small lake and a dozen mallards got up with much squawking and flapping of wings. We moved cautiously then to the far end of the lake, where tall grasses ran to the water’s edge and we were able to crouch behind a half-sunken windfall. The grass protected us from sight from all angles except directly overhead.

We didn’t have to wait long. I think it was the same flock that had got up when we first arrived. Anyway they circled low overhead and then with noisy splashes settled at the far end of the lake. We waited for them to feed closer. Less than 10 minutes later a larger flock showed over the trees. Circling high over our heads they came, their beautiful wings glistening in the midmorning sunshine. Then, after banking as neatly as a flight of fighter planes, the flock of 20 mallards splashed down just out of range of our shotguns.

As the second flock began feeding, still another flight came in, flying low right over our heads, their legs lowered for landing. As I moved my gun in readiness the leader must have spotted us. The ducks changed course too late and rose right into the path of the flying shot. Several of them smacked into the lake almost at our feet. The two other flocks got up fast and took off across the lake, well out of range.

We hiked from one lake to another, getting a bagful of fine birds. Then we took time out for lunch on a moss-covered bank in the warm afternoon sun.

“We’ll go back after lunch,” Old Cap suggested, “by way of my lookout. Maybe we can spot a moose out on the slough flats and plan how to get him tomorrow.”

Our packsacks bulging with ducks, we threaded our way through the timber, the soft deep moss springy underfoot. The fall colors lit the trail with glory.

The wind settled down for the evening as we emerged from the trees onto the lookout. The smooth lava surface jutted out from the timber for about 100 yards, making a point like a huge V. From the point of the V the lava was broken away, leaving a sheer wall that dropped 200 feet to a tumbled broken slide, which continued down to the edge of the slough. Both sides of the V had these same precipitous walls, so the only way to the lookout point, or back from it, was through the base-line of timber and across the 100 yards of bare lava to the edge of the precipice.

We sat on the edge of the rock at the point of the V, our legs dangling over the precipice, and searched the flats far below, looking for moose. The last rays of the setting sun lit the distant Saw Tooth Mountains away to the west, while a quietness settled like a huge soft blanket spread over the wilderness.

I had shipped a bootful of water at the last lake while retrieving a duck. I took the boot off, and as I emptied it over the precipice a queer feeling of uneasiness came over me. Some subtle sense of danger slowly developed, making a cold shiver creep up my spine. It was like the shock a man feels when he’s out alone and hears the drawn-out howl of a timber wolf. As I pulled on my boot I felt, rather than saw, Old Cap reach for his gun beside him. Somehow we were standing, although I don’t remember getting to my feet. I remember that my shotgun was empty, that the last two shells I had borrowed from Old Cap were gone.

Together, without a word, we turned toward the timber. I glanced at Old Cap and saw his jaw muscles twitch a little as he held his 12 gauge loosely in front of him. I looked past him to the edge of the timber.

Facing us, blocking our only possible exit, was a massive grizzly sow. Beside her, two five-month-old cubs stood watching us. One of them trotted out toward us in a playful gallop, like a child’s puppy chasing a ball. With a grunt the old she-bear rolled out after it and cuffed it with a huge paw, sending it spinning through the air. For a moment she just stood there, eyeing us, making me wish for that heavy rifle again. Then she turned and chased her cubs back into the woods.

With relief I grabbed Old Cap’s arm and headed for the side of the timber and the trail to our canoe, away from the bear before she might change her mind. It was a mistake. Before we had gone 10 paces a roar shattered the stillness. With a gasp I turned and saw the huge sow start toward us on the run, her mane bristling over the huge hump above her shoulders, her enormous head hung low and swinging from side to side. She seemed to roll, rather than run, across the open space between us. The silver hide rumpled and stretched over the massive body. She looked as big as a mountain in that half-light.

We backed almost to the edge of the precipice. There was nowhere to run, no tree to climb, and it was impossible to climb down the sheer wall behind us. I looked at Old Cap. His face was set. His firm jaw stuck out a little as he watched the oncoming half-ton of fury.

Halfway across the open space she stopped and reared up on her hind legs, raising her front legs toward us as if gauging our size. The long curving claws of white ivory glistened their deadly threat. The lighter marking on her chest between the upraised front legs showed where her heart lay beneath that silvery coat. God, how I wished for a rifle at that moment!

With a bellow the sow came down on all fours and started the final charge. I know I shuddered. Old Cap did not move. He just stood there, his gun held lightly in front of him, both barrels loaded and cocked, waiting for that red-eyed monster to sweep us into eternity.

Those moments seemed like a thousand years. I could see the mean beady eyes, the huge slavering jaws. This could not be truly happening; this must be some hallucination! On she came — 100 feet, 50 feet, 30 … would Old Cap never fire? I stood frozen to the ground. Slowly the old man raised his gun. Deliberately he took aim and waited. With all the vast knowledge of experience he waited with a terrible patience and nerve.

The bear was almost on top of us when, with a deafening roar, the shot from both barrels smacked into that enormous shaggy head. Cap and I both jumped aside. The huge beast tried to slew around as the shot, striking like a ball, blinded both eyes. But the impetus she had gained in her mad charge carried her past us, and in a flash she was over the precipice. I heard an agonizing death bellow, followed by the slide of rocks as she struck the broken basalt 200 feet below.

Read next, also by Anton Money: A Bull-Moose Brawl and Meat-Packing Sled Dogs: A Mountain Man’s Last Hunt Before Winter.

Without a word we headed for the trees and came down the steep trail toward the canoe. We clambered over the broken lava and came to where the grizzly lay, stretched out over the jagged chunks of dark rock. The whole top of her skull was gone, and blood was streaked along her back. The massive muscles of her front legs hugged a boulder the size of a man.

A hoot owl sounded off in the nearby trees as we threaded our way back to the canoe. Praise beyond words for Old Cap’s nerve choked in my throat.

The post I Was Trapped on a Cliff, Staring Down a Charging Grizzly appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/survival/lookout-grizzly-charges-alaska-hunters/