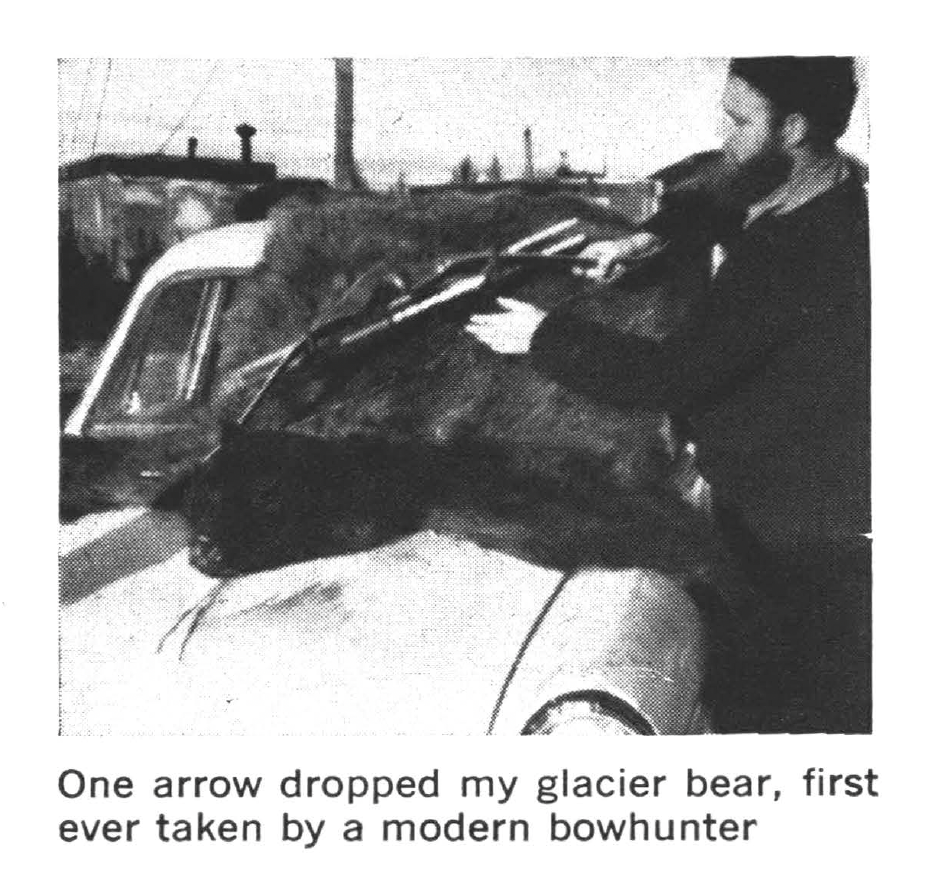

I Tagged the First Glacier Bear Ever Taken by a Modern Bowhunter

This story, “My Bear Was Blue,” appeared in the June 1973 issue of Outdoor Life.

I was taking one step at a time, and very slowly at that, stopping after each to look and listen. Somewhere below me in the thick brush that lined both sides of the trail was a bear, a rare and beautiful trophy that I wanted more than any other animal I had hunted.

I moved a cautious step, paused-and heard something heavy walking through the thick cover on my left. Then I saw the brush move and knew exactly where he was.

The thickets were chest-high, and all I could see were the tops swaying as he came on. He was only a few yards away, and I was standing in plain sight on the trail. I didn’t dare move, not even to bring my bow up to shooting position. I think I held my breath.

The footfalls and rustling came abreast of me and moved toward the trail. Then, no more than 40 feet away, he stopped just inside the cover, and I knew he was listening and looking, just as I was. If I hadn’t held my breath before, I certainly held it now.

Nothing happened. I didn’t know whether he had seen me, scented me, or was just being cautious. Would he keep coming, or wheel and pound off at a run, or simply vanish in that elusive way that spooked bears can? A light wind was blowing. Save for its low sound, the woods were silent.

Then I heard a muffled sound of movement, and the bear poked a coal-black head — at least it looked coal-black — into sight a scant dozen yards from me. My heart skipped a couple of beats and then started to hammer hard enough that I half suspected he would hear it.

The hunt had begun four days before. This was the third week in September 1972, and silver salmon were running in the Situk River about eight miles east of Yakutat, Alaska, where I live. I was helping Bill Fraker, a commercial fisherman, with his salmon fishing. We took a good catch and cruised toward the mouth of the Situk where a cannery truck was waiting to buy the fish.

Read Next: The Best Compound Bows, Tested and Reviewed

Bill had a party of friends who were sportfishing for silvers. They were staying at a cabin about a mile upriver from the Situk’s mouth, and when our work was finished we hiked up to have lunch with them.

They were taking some beautiful salmon, they said. But they were also having trouble with a bear that was getting into their fish during the day while they were away from the cabin. They were still telling us about the bear when we heard a racket outside, and then the clatter of their trash can being knocked over.

We ran for the door. I was the last one out, and I glimpsed what looked like a dusty black bear lamming into the brush. “That’s a glacier bear!” Fraker yelled. I didn’t know much about glacier bears, but I knew enough to be sure that I wanted a crack at this one.

They are a silver-blue phase of the black and are found only along a stretch of coast in southeastern Alaska. The books say their range extends from Mount St. Elias to the region of Glacier Bay, but the guides I know tell me that these bears are rarely encountered southeast of Mount Fairweather.

Some authorities rate their oddly colored pelt the most beautiful of any of the black-bear family, including the cinnamon and the milk-white Kermode. Glacier bears are decidedly rare, and on the average fewer than two are killed each year. If I took this one, he would be my third bear. I didn’t know then that there was no record of any of his kind ever having been killed with a bow.

I’m 25 years old and have bowhunted since my early teens. I was born and grew up at Ogden, Utah. I began hunting with a gun, then joined a Boy Scout troop that was hooked on archery. The troop hunted rabbits together, and shortly after I acquired my first bow I turned to bigger game. When I started after the glacier bear, I had killed six deer, an elk, and two black bears with a bow.

I was discharged from the Air Force in December 1969, and I put in the next year prospecting at Cape Yakataga, about 100 miles west of Yakutat. I’m not married, and I’m free to hunt and fish as much as I like, which is a great deal. I have a small gold-mining operation about 80 miles north of Yakutat. When I’m not at the mine or hunting, I work at construction. It’s a way of life I like.

I killed my first black bear while I was at Yakataga, taking four arrows to do it. He was a nice one, and ever since then I have considered bears among the most exciting North American trophy animals.

That first hunt was lively even if it didn’t last long. Pop Eggebroten, a good friend who lived near me, saw a hefty black walk across the road near his place one early-spring day in 1970. He knew of my interest in bowhunting, and he came after me in a hurry.

“I’ve just seen a bear I think you can get,” he said.

That was all the invitation I needed. We trailed the bear through thick stuff, got near him, and I worked in close enough for a shot.

My first arrow sliced into his right shoulder, but the heavy bone of the shoulder blade stopped it. The cedar shaft broke on impact, so quickly that it appeared to bounce off.

The bear lit out, and I sent another arrow on the way fast. It hit low in the right front leg, hard enough to break the bone, but it didn’t seem to slow him a bit.

The next arrow glanced off a small tree and missed clean. Then I put one where I wanted it, square in the lungs. The bear ran a short distance, collapsed, and was dead in two or three minutes.

“I’m sort of glad he didn’t turn on us when he felt that first arrow,” Pop said with a grin.

We had no gun, and it hadn’t occurred to us that neither was carrying even a knife.

“Next time I go after a bear with one of you bowhunters, I’ll have something along for backup,” Pop added. “You can kill ’em, all right, but you don’t do very well at knocking ’em down.”

The next bear I took, later that year, I did a better job on. I was hiking back to my cabin and surprised him raiding it. I put my first arrow into his heart, and he died almost in his tracks. I was sorry Pop wasn’t there to see it.

I didn’t mention it, but I was thankful that no one had had a gun. I’d have a chance to take the bear with a bow.

When we boiled out of the fishing cabin that day and Bill Fraker shouted that the bear vanishing in the brush was a glacier, I was inclined to doubt him. I had never seen a bear of that color phase, but this one had looked like an ordinary black bear to me. I said as much.

“He was a little dusty,” I told Bill, “but are you sure he’s a glacier bear?”

“You bet I’m sure. He was in shadow. Catch him out in the sun, and you’ll find he’s a silver-blue all the way from his head back.”

We had no more than started back to our boat when Fraker was proven right. We rounded a bend in the trail, and our bear was standing on the river bank about 100 yards downstream. I couldn’t mistake his odd gray-blue color in the full light. I made up my mind that I was going to gather him in.

Bill had the same idea.

“That’s a trophy worth going after,” he told me.

I didn’t mention it, but I was thankful that no one had had a gun. I’d have a chance to take the bear with a bow.

Fraker’s friends were leaving the cabin later that day, but he and I talked it over and agreed that the bear would likely hang around for a few days, since he had found food there. He’d be hoping to find the garbage can refilled or a fresh cache of salmon.

I could see that Fraker wanted the bear as much as I did. But he made me a very fair offer. His son Bob was also a bowhunter.

“Tell you what I’ll do,” he said. “I’ll give you first chance at him if Bob can hunt with you. Whichever one of you kills him, you can share the honor of taking a glacier bear on a bowhunt. So far as I know, it’s never been done.”

I accepted on the spot. Having thought things over, I was sure Bill was right. From all I had heard, if Bob or I connected, the bear would be the first of his kind ever taken by a modern bowhunter. It was an exciting prospect.

It was agreed that Bill would back us up with his rifle. If Bob or I had a chance and muffed it, or if it seemed likely the bear was going to get away, Bill would take a hand.

The three of us were back on the Situk the first thing the following morning, and we hunted hard all day. But we could find no sign of the bear. Bob had a moose hunt planned, and that night he decided to give up on the bear and go after moose.

His dad and I went back to the Situk and put in another hard day looking for some hint that our bear was still hanging around the cabin. We didn’t find so much as a fresh track, and the next morning Bill announced that he too was quitting the hunt. I felt he had decided that there was no longer a chance of taking the bear.

But I wanted to make one more try. I went back alone that morning but had no luck. I left the cabin about noon and headed for the beach. On the way I stopped for a last look at the bear’s four-day-old tracks along the river bank. It was a farewell gesture-I had resigned myself to the fact that we had drawn a blank.

As I studied the old tracks, I wondered where their maker had gone. For some reason, I raised my head and glanced downstream, and my heart skipped. About 350 yards away a bear was walking slowly upstream toward me. When the sun touched him, I could see that his pelt was an unmistakable silver-blue.

I was in plain sight, and I stayed rooted in my tracks. The bear was feeding on salmonberries. I watched him for more than half an hour. It took him that long to move 150 yards in my direction. All that time I didn’t dare make a move.

When the sun touched him, I could see that his pelt was an unmistakable silver-blue.

Finally, 200 yards from me, he turned and disappeared in the brush and timber. I dodged into the brush too, hoping to head him off.

I moved carefully, a step or two at a time, stopping to listen. I came out on a bear trail that I had found earlier and turned onto it, working my way downstream toward the place I had seen him last. It was easier to move quietly on the well-used trail, but still I knew better than to hurry.

I figured I must be getting pretty close to him when I came to a place where I could hide within good bow range of the trail. If he had made up his mind to follow it back to the cabin, as I suspected, I wouldn’t have long to wait.

I waited more than an hour and I saw or heard nothing except a beautiful bald eagle that perched in a dead cottonwood, watching for salmon in the rapids, and a pint-size red squirrel that made me jump almost out of my boots when he exploded into furious activity 10 paces behind me. For an animal of his size, that squirrel was incredibly noisy. He stirred up more commotion than I had expected from the bear.

That was as long an hour as any I can remember. I gave up finally. Wherever my quarry had gone, it was evident that he did not intend to walk past me on the bear trail. I figured he had probably turned back downstream, so I moved off in that direction, still walking cautiously. I had very little hope of making contact with him now, but I couldn’t afford to overlook the basic rules of bowhunting.

I hadn’t taken a dozen slow steps when I heard him coming. I stopped and waited, my pulse racing, while he walked abreast of me, turned toward the trail, and poked his head cautiously out of the brush.

I thought he was a different bear, for all I could see of him looked jet black. But then he moved a bit, and I made out the telltale bluish color at the base of his skull.

For an eternal two or three minutes we didn’t move a muscle. I was sure he hadn’t made me out, but I was equally sure that if I tried to bring my bow up, the movement would catch his eye. And anyway, so long as I could see only his head, I had no intention of risking a shot.

My two earlier bears had taught me that with such a big, tough animal, there is only one place to put an arrow for a quick and certain kill. Aim for the rib cage, trying for the lungs and heart. Until this blue bear showed me the right part of his anatomy, I’d wait.

Finally he swung his head and looked straight at me, and it seemed impossible that he could fail to discern the man shape in the trail some 35 feet away. But he showed no hint of alarm, and looked the other way. I raised my bow a few inches, moving in slow motion.

We repeated that performance half a dozen times, as he looked toward me and then away. At last I was ready for the draw.

I drew the bowstring back to my jaw while he was looking away, but still he wouldn’t step clear of the brush. My bow was a 52-inch Kodiak Magnum, made by the Bear Archery Company, pulling 48 pounds. It’s hard to hold a bow of that power at full draw for more than 10 or 12 seconds, and my arms started to shake. But I was waiting for what I knew would be the chance of a lifetime, and I wouldn’t risk a shot until I could send my arrow where I wanted it to go.

The wait lasted hardly more than a minute, but it seemed a quarter-hour. At last the bear looked down the trail at me once more and then stepped clear of the brush, standing almost broadside, angling a little away from me — exactly the target I wanted. The bowstring slipped smoothly off my fingers, and the razorhead flew as if it knew where it was going.

It knifed in about two inches behind the right shoulder, sinking almost to the feathers. I learned later that it split one rib, cut a two-inch gash across the top of the heart, and went all the way through both lungs. I had made a perfect bowshot.

The bear made no sound. He whipped his head around, bit angrily at the arrow, and then for the first time he appeared to see me. He leaped sideways into the brush. When I saw blood gushing from his mouth I knew he was as good as dead. I did not shoot again.

He made two or three jumps, as if trying to got away from what had hurt him, and then I heard him collapse in thick brush. After a brief thrashing, everything was quiet. I realized then that my knees were shaking so hard they could barely hold me up.

I heard voices moving along the trail from downstream, and Johnny Nelson and his wife, local Natives, came into sight. They were picking highbush cranberries. If they’d arrived a minute or two earlier they would have cost me my chance at the bear. I still shudder when I think of that close turn of fate.

I was waiting for what I knew would be the chance of a lifetime, and I wouldn’t risk a shot until I could send my arrow where I wanted it to go.

Johnny and his wife walked up to me, and I blurted out my big news.

“I just killed a bear,” I said. Johnny all but dropped his berry pail.

“With that?” he said, pointing to my bow.

“With this,” I assured him. His next question was logical enough. It was also urgent.

“You sure it’s dead?” he asked. “He has to be dead. He isn’t making a sound. You can’t even hear him breathe.”

The two waited while I walked carefully into the brush. The bear was lying stone-dead just 40 feet off the trail, the most-beautiful animal I had ever seen.

A male, he squared six feet three inches. At first I believed he would rate top place in the glacier-bear category in the Pope and Young Club’s record list, since he would be the first one of that kind recorded as killed with a bow.

But I learned that Pope and Young, like the Boone and Crockett Club, does not have a separate category for glacier bears. Instead, the blue bear and even the white Kermode are lumped in with other color phases of the black bear for purposes of record-keeping. So there seems no chance that my bear will be No. 1 on any official list.

The skull has not yet been measured. But he was a big bear, and those who have seen it say he will undoubtedly end up somewhere among Pope and Young record black bears. Whatever happens, he was all the bear a bowhunter could ask for.

Read Next: Fred Bear in Alaska: Bowhunting a World-Record Brown Bear

He is to be mounted whole, and I have arranged to loan the mount to the Fred Bear Archery Museum at Grayling, Michigan. It is to be on display there for 10 years and then will be returned to me.

I expect to bowhunt the rest of my life, but I doubt I’ll ever take another trophy to match that magnificent blue pelt.

The post I Tagged the First Glacier Bear Ever Taken by a Modern Bowhunter appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/blue-color-phase-black-bear/