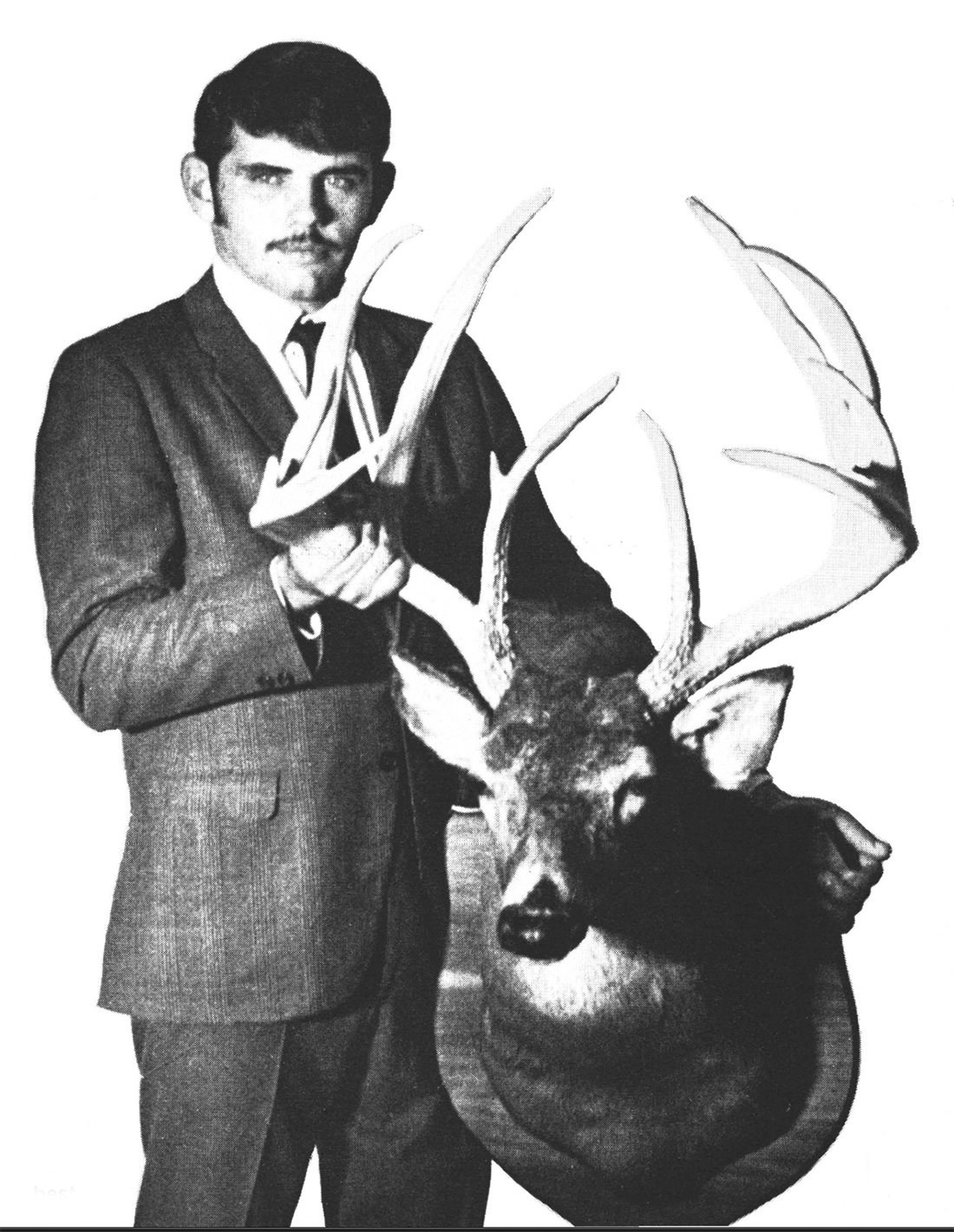

How I Still-Hunted the Second Biggest Buck Ever Tagged in Missouri

This story, “A Phantom of Record,” appeared in the November 1971 issue of Outdoor Life. The Brunk buck remains the No. 2 biggest typical ever killed in Missouri, according to Boone & Crockett, and the 25th largest of all-time. It was taken in Clark County, Missouri, on Nov. 22, 1969.

Three does exploded from the brush-covered draw as if they’d had a running start. They bolted across an opening and then melted into a small patch of timber 200 yards ahead. I heard those whitetails almost as well as I saw them. It was bitter cold, and the farm country in northeastern Missouri was coated with heavy frost that crackled as the deer raced away.

Dawn was a half-hour gone on that November morning in 1968. I wasn’t interested in the does, but I wondered why they ran into a small thicket when bigger woodlands were close by. Walking was so noisy that a quiet stalk was impossible. When I got within 150 yards of the thicket, the three deer hightailed out across an open beanfield and headed for a larger woods a quarter-mile to my right. I was watching them run when a sudden crashing of brush erupted where they had just been. I whirled around, but a buck was already jetting full speed along the route the three does had taken.

As soon as I spotted him I choked up. There was no doubt that I was looking for the second time at the Phantom. He was enormous, but it was his rack that took my breath away. The antlers were huge, and the tines were almost white. They looked ghostly against frost-covered hills.

I almost stumbled as I shouldered my Springfield single-shot 20-gauge shotgun. I took a careful lead on the streaking buck and fired. The slug exploded a shower of frost low and behind the deer. I broke the action, fumble-fingered another shell into the gun, held a little higher, moved the barrel farther ahead of the target, and squeezed the trigger again. A second cloud of frost erupted off the ground, just under the buck’s belly. Then he ran over a knoll in the beanfield and momentarily disappeared.

When the buck came into view again he was still in the open but too far away for another try with the shotgun. My breath went out with a helpless gasp as I watched him run across the field and disappear into the timber.

For minutes I fought despair. Then my mood changed to anger. I got about as mad as a 16-year-old boy can get. I wasn’t mad at myself; I was mad at my dad. If he hadn’t insisted that I hunt deer with a shotgun, I might have killed that buck.

“Sure,” I told myself, “if I’d had a rifle, I could have kept shooting.”

I ran all the way home, stampeded into the house, and blurted out my story to my folks. Without being disrespectful I made it clear that shotgun slugs are useless for shooting at long-range bucks.

“Somehow,” I emphasized, “I’m going to have a new rifle come next deer season.”

I’m 19 now, and I attend Northeast Missouri State College, where I’m majoring in animal science. I plan to get a bachelor’s degree and then go on to some university and get a master’s degree in wildlife management.

My folks own 245 acres of fine farmland four miles north of Revere, Missouri. Dad rents an additional 45 acres. Our hog herd consists of registered Hampshires, and we grow a lot of corn to feed them. We raise up to 1,000 head of fat hogs each year.

The terrain around our farm is ideal deer country. Oak, hickory, and other hardwoods make up most of the woodlands, and we also have a lot of cedar. In places the underbrush is so thick that you can hardly fight your way through it.

Our timber areas aren’t vast like the forests of some states in the North. Most of them vary from less than an acre up to about 100 acres. The trees border pastures and fields of corn and beans. The woodlands are hilly, with numerous ditches and draws that run into croplands.

Our whitetails don’t have any wintering problem. They have unlimited food, and the thick woodlands off er perfect cover. The high mineral content of our soil produces big-racked bucks, especially north of the Missouri River.

Back in 1936 Missouri’s statewide deer population was estimated at 2,000 whitetails spread over 28 counties. Thirty years later, in 1966, hunters harvested 28,423 deer in Missouri. This dramatic increase is the direct result of fine game management by our state conservation department. Some of our northern counties have shown amazing herd growth. Our farm is in Clark County, where the deer kill jumped from 56 in 1960 to 239 in 1968. Biologists say Missouri’s whitetail herd is still growing.

I was lucky that my deer-hunting career was getting under way at the same time the herd became well established. But even before then I was an avid hunter. Dad has been a hunter and trapper all of his life. I used to follow him on small-game hunts until my ninth Christmas. That’s when he gave me the 20 gauge and I branched out on my own.

There was no doubt that I was looking for the second time at the Phantom. He was enormous, but it was his rack that took my breath away. The antlers were huge, and the tines were almost white. They looked ghostly against frost-covered hills.

During the next few years I supplied the makings of many quail, rabbit, waterfowl, and pheasant dinners. When game seasons weren’t open I went after varmints. But Dad wouldn’t give me permission to hunt deer till I turned 14 in 1966.

I couldn’t wait for the fall firearms season, so I bought a fiberglass bow that had a 50-pound pull. I bowhunted without success from the first of October till the gun season opened. I was after deer just about every minute I wasn’t in school, doing chores, sleeping, or eating. I found many feeding grounds. bedding areas, and well-traveled runways. I saw plenty of deer, but I wasn’t skilled enough to get within bow range of them.

On the first day of the firearms season I hunted with Dad, but neither of us got a shot. The next day Dad had to work, so I was on my own. I hunted all morning without seeing a deer, then walked home for lunch. I helped with chores until midafternoon and then headed out to stillhunt some nearby timber.

An hour or so later I jumped a big buck that was bedded under some cedars. The deer lined straight away across a small clearing. He was about 30 yards out when I aimed at his neck and fired. The 20 gauge slug went true, and the buck pitched face-down as if he’d been clubbed. He was dead when he hit the ground. I didn’t realize what a fine trophy I’d taken until Dad and I got the buck home. The field-dressed carcass weighed 215 pounds, and the 12-point rack was massive.

“Jeff,” Dad said, “your first buck is probably the biggest you’ll ever shoot. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bigger deer. You’re a lucky hunter.”

At the time, I figured Dad was right. That was before the Phantom came into my life. In Missouri it’s legal to take one deer with a gun and another with archery gear, so I was able to keep hunting till the end of December. I scored on a button buck, but most of the time I was developing my hunting methods.

I soon found out that when deer are moving — early and late in the day — it’s best to take a stand. If they’re traveling to feeding and bedding areas, they’ll walk within easy range if you’re in the right place. I learned to pick spots where two runways meet or cross. In such places you double your chances of seeing deer.

It surprised me, though, to discover that I saw more deer while I was stillhunting. While I was first learning stillhunting techniques I’d just get glimpses of white flags flashing through the timber. But as time went on I learned how to get closer to the animals.

I believe that a deer hunter is almost bound to find action if he has an intimate knowledge of his hunting area. If you know where a herd feeds, travels, and beds down, half of your stillhunting problems are solved. Then you can concentrate on sneaking into known deer areas over totally familiar terrain, taking precise advantage of wind conditions and known cover. A skilled stillhunter sees plenty of deer because he knows where the animals will be at all times of the day, not just in early morning and late afternoon. This principle doesn’t hold true in vast forests, but it works great in the scattered timber of farm country.

My secret to success with this system is being in the woods so much that I practically live with the deer as they move about. During the off season after I scored on the 12-pointer, I was afield enough to discover some astonishing facts. I learned to recognize individual bucks, and I could come close to predicting what time of day they would move through a specific area. I knew how many deer were in certain timber stands and what travel routes they used when hungry, tired, or spooked.

Only one thing stumped me during those scouting sessions. Several times I found an enormous set of deer tracks. The imprints were very widely spread and oddly flared. Often I checked tracks of big bucks that I had jumped, yet I never matched any fresh tracks with the huge mysterious imprints.

The puzzle was solved two days before the 1967 gun deer season opened. I was finishing a day of quail hunting with three friends. It was dusk when we came out of some timber and headed for a road. Suddenly we spotted three deer standing near the edge of a field 300 yards away. At first I thought I was looking at a doe and two fawns. Then I realized that I was staring at two adult does and a giant buck.

The more I studied the buck the more I wondered if my eyes were deceiving me. His antlers were almost white, and for a moment I thought I might be looking at dead tree limbs. Then he moved slightly, and the tremendously long white tines of his rack came into clear focus.

I hardly had time to note that the buck was far larger than any I’d ever seen. He just seemed to evaporate. But I caught one glimpse of him while he was running, and that sight will be burned on my mind forever. He looked more like an elk than a deer. He ran with a majestic gait. His head was high, and it didn’t seem to move at all.

I rushed across the field and looked at the enormous tracks. They were the same widely spread and unusually flared imprints that I’d seen before. A queasy feeling came over me when I realized how cunning that whitetail must be. It was hard to believe that I had never spotted him during my months of dedicated scouting. That’s when I named him the Phantom.

The huge buck eluded me during that fall’s gun and bow seasons. But I followed his tracks several times, and they helped me determine his home area. There wasn’t much doubt that he stayed in an area of a few square miles just east of our farm.

I didn’t say much to anybody about that buck during the hunting seasons, but later I decided to find out if any of the neighbors knew about him. I drew blanks with everybody.

“You sure you saw a buck that big?” asked one farmer. “And you claim his antlers are almost white? Seems like such a buck couldn’t help but be noticed in farm country.”

When the summer of 1968 came along I spent days following the Phantom’s tracks. They told me quite a story. I discovered that he never traveled on specific trails and that he never came out into feeding areas on routes used by other deer. He seemed to wander aimlessly through his territory, and I decided that I’d never get him by taking stands along trails. My only chance would be stillhunting.

That fall I missed a chance at the Phantom in the incident I described at the beginning of this story. My message to Dad about the problems of hunting deer with shotguns rubbed off, and he let me use his Model 94 Winchester .30 /30 several days when he had to work. One morning while stillhunting I jumped a nice 10-pointer and anchored him with a shoulder shot. For the rest of the year I switched to bowhunting, but I never saw the Phantom again.

When I graduated from high school the next spring my folks presented me with a new Browning semiautomatic Grade II .30/06 rifle. I fitted it with a l½X to 4½X Weaver scope with Dual X crosshairs. I wanted a low-power scope since its wide field of view would be excellent for the snap-shooting chances that occur in stillhunting.

“You sure you saw a buck that big?” asked one farmer. “And you claim his antlers are almost white? Seems like such a buck couldn’t help but be noticed in farm country.”

When the November 15 to 23 gun season opened, Dad and I were joined by my Uncle Larry Brunk, who is a dentist from Burlington, Iowa, and my cousin Greg, a college student from Burlington. Dad dropped a six-pointer the first morning. Late the next day Greg and I spotted a deer running through a cornfield east of the farm. The animal stopped near the edge of some trees 75 yards away, but in the fading dusk we couldn’t tell if it was a buck or a doe. Then the deer moved its head slightly and we could see a rack. Greg’s rifle roared, and the seven-pointer went down with a broken spine.

That fall I was attending junior college in Keokuk, Iowa, about 20 miles from our farm. I was living at home, but I didn’t have much time to hunt except on weekends. My Uncle Larry came up on the Wednesday after opening day and killed a large 10-pointer. Now I was the only one in the foursome who hadn’t scored.

The next Saturday I stillhunted from dawn to dark and jumped two does for my efforts. I went to bed early that night because Sunday would be my last full day of hunting during the gun season. I had a new plan.

I’d discovered that the Phantom had a habit of bedding down in tiny timber patches on ridges close to big woodlands, especially after rifles began banging. I suppose he chose these spots so that he could see in all directions and, when trouble developed, could drop down into the big adjacent woodlands. I planned to stillhunt every likely piece of small brush in his area.

Dawn came on chilly with a slight overcast and a light breeze. I began to follow my schedule of stillhunting ridges. My plan was to walk silently to likely spots, stop and look, and then move on.

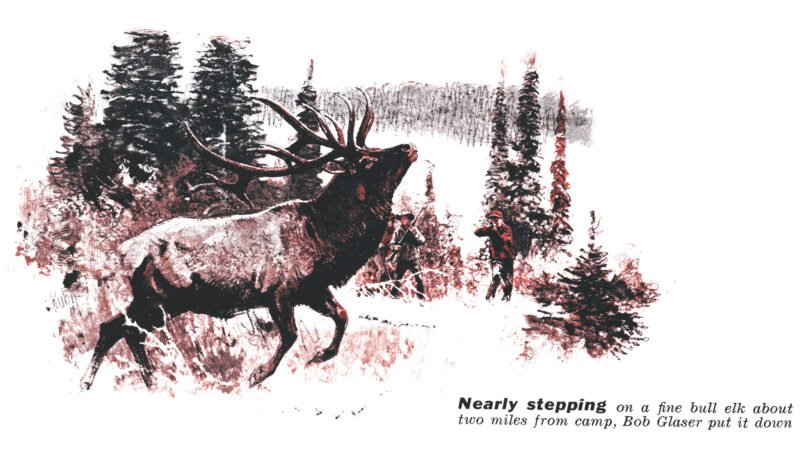

About midmorning I walked down a ridge, crossed a creek, and started up a hill leading to another ridge covered with scattered clumps of cedar and scrub oak. I was moving slowly, and the grass allowed silent travel. As I look back on the situation, I’m sure the Phantom never suspected I was on that hill. I’m convinced he simply decided to move on his own.

I was halfway up the hill when I noted a slight movement in a cedar clump 100 yards above me. Then a huge white set of antlers appeared above the cedars. I didn’t see any other part of the deer; just that ghostly white rack seemingly hung from the sky.

In seconds the antlers moved as if they were floating in air. The buck was walking very slowly. I lined my scope on an opening in the cedars and waited. I was suddenly afraid that the Phantom would hear my heart banging against my ribs.

Then his body was clear of the trees. The enormous brown shape offered a perfect broadside target. The crosshairs settled on his shoulder, and my rifle roared.

I was positive the buck would collapse; I knew the 180-grain slug had gone true to its mark. Instead, he bolted as if he hadn’t been scratched. He wheeled toward some thick oaks and ran like lightning. I recovered fast enough to get in one snap shot before he disappeared into the timber.

It was deathly quiet now, as if the whole episode had never happened. I ran to the spot where the buck had been standing, but I could find no trace of hair or blood.

I followed the familiar wide-splayed tracks till I came to the paved highway lead’ng north out of Revere. When I crossed the road I got another shock : I couldn’t find his trail. It dawned on me that the smart old whitetail had run the pavement to hide his hoofprints. The thought almost made me sick. I still hadn’t found any blood or hair. The buck apparently was alert and not hurting at all. For a moment I wondered if I could possibly have missed the standing, wide-open target.

“No way,” I told myself. “That deer has to be hit.”

I reasoned that if he was wounded he would run the road downhill, then turn off into a brushy draw leading to big timber. Several of these draws cut across a beanfield. I checked the largest one first. I found no sign of the buck, so I walked to the next draw. I didn’t get very far into it when a sudden crashing of brush erupted 50 yards ahead of me. I couldn’t spot the Phantom, but from to run across the beanfield. I smashed frantically ahead, hoping that I could get a shot at him in the open. I was too late, but I kept on running till I was across the field and into another draw.

Minutes later I jumped the buck again, not more than 40 feet ahead of me. I got a good view of that white rack and huge body, but the thick brush swallowed him so fast I didn’t have time to shoot. When I picked up his tracks I was elated. I found a few drops of blood where he’d been standing.

My only choice was to stay on his trail. About two hours later I jumped him out of a creekbottom while I was walking down a hill. He busted out at full speed 100 yards away but relatively in the clear. I thought I had him, but he didn’t react at all to my three shots.

I got a good view of that white rack and huge body, but the thick brush swallowed him so fast I didn’t have time to shoot.

About 15 minutes later I spotted the huge deer slinking through thick brush 200 yards ahead. I barely had time for one snap shot. I kept stalking on and soon spotted him 75 yards away in some cedars. He was moving slowly, and for the first time I realized that he must be badly wounded. I followed him in my scope until he moved into a tiny clearing. Then I carefully squeezed the trigger. When my rifle roared, the Phantom crashed to the ground.

I ran up to the dead deer and stared at the white antlers. The 13-point rack was even bigger than I had pictured it. As I field-dressed the buck I discovered that one bullet had pretty well shattered a shoulder blade, and other slugs had disintegrated one lung and the tip of his heart.

It took me 20 minutes to run home, but it took three hours for Dad, Uncle Larry, Greg, and me to drag the monster buck out to a road. We loaded him in our pickup truck and then drove to a conservation-department deer-checking station. Later we hung him in a locker plant that has an eight-foot-high ceiling. We hauled him up by his hind legs with pulleys until his back hoofs touched the ceiling. His head and rack were still on the floor.

After I got the Phantom’s mounted I took it to Jerry Barton, our Clark County game warden. Jerry was so sure I’d taken a new state-record whitetail that he got in touch with Dean Murphy, superintendent of game management for the Missouri Department of Conservation. In the summer of 1970 I received a letter from Dean.

“If Jerry’s figures are correct you may have more than a new state-record whitetail,” Dean wrote. “I’m an official scorer for the Boone and Crockett Club, and I’d sure like to measure those antlers. I’ll check them when I get up in your area.”

On September 16 Dean measured the antlers and came up with a preliminary score of 197 2/8. That’s 13 6/8 better than the score of the former Missouri-record typical whitetail, taken by Marvin Lentz of Sumner.

My biggest surprise was yet to come. On May 5, 1971, the Phantom won the Boone and Crockett Club’s award as the highest-scoring typical whitetail killed in North America during the club’s 14th big-game competition, covering the years 1968 through 1970. My trophy’s final official score was 199 4/8, just 7 1/8 less than the score of the world-record typical whitetail and good for the No. 4 spot in the club’s overall records.

The news left me flabbergasted. I never dreamed it was possible for a Missouri farm boy to kill such a trophy just a few miles from home.

The post How I Still-Hunted the Second Biggest Buck Ever Tagged in Missouri appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/giant-missouri-typical-buck/