Carmichel in the Middle East: Risking Our Lives to Hunt Iranian Ibex

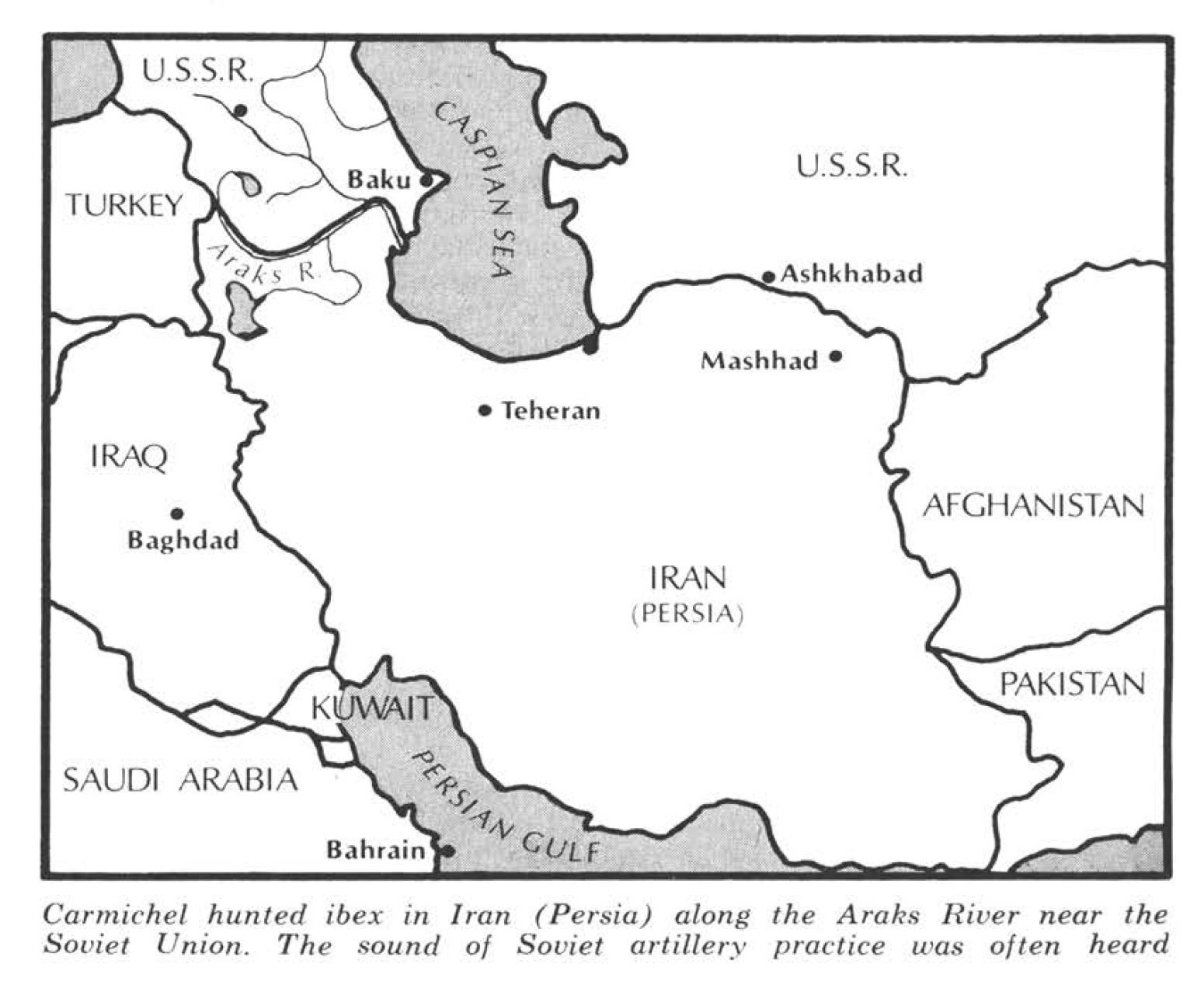

This story, “Hunting at Russia’s Doorstep: Horns That Make Your Heart Skip,” appeared in the April 1975 issue of Outdoor Life. Farsi is the predominant language spoken in Iran.

“As soon as we get back to camp I’m going to check the scope on that rifle,” I said to Hooshang. He nodded wearily.

Except for my terse remark, our lunch of thin labosh bread, tart white cheese, which the Iranians call paneer, and cups of scalding tea was eaten in silence. The usually garrulous Iranian shepherds who served us as guides and porters remained silent and gazed into the distance. I got the distinct impression that not speaking or looking my way was the result of politeness. I might, they thought, take their words or gaze as a reproach for having muffed a hard-earned shot half an hour before.

I did not apologize to them for missing. Missing, like hitting, is a part of hunting. Apologies and explanations are not required or expected. And yet I was miserable over that miss. While I sipped my tea Iranian fashion, with a lump of sugar held behind my teeth, I remembered how I had busted a gut trying to take a fine trophy, only to miss at the last moment.

The hunt had started out in fine style and with great promise. Fred Huntington, the Oroville, California, manufacturer of RCBS reloading equipment, and I had left Los Angeles on the last day of the year and rang in 1974 somewhere over the North Atlantic in the cozy comfort of a Pan American jet. We toasted the New Year, each other, and our plans for a good hunt in Iran.

Fred has hunted in many parts of the world, including several African safaris, but like me he had never hunted in Iran before. Some months earlier we had been struck by the notion that we ought to have a try at Iran’s game, so we booked a hunt with Iran Safaris Ltd. through Klineburger Brothers, Seattle. We planned to hunt red sheep in the Royal Preserve near Teheran, the beautiful Urial sheep in northeastern Iran, and the elusive little Armenian sheep as well as fabled ibex near the Turkish and Russian borders of northwestern Iran.

With 1974 barely a week old I found myself sitting on a mountain so close to the Soviet Union that a loose stone would have splashed down into the Araks River, which forms part of the border between Iran and Russia. In the distance there was intermittent thundering that I later learned was Soviet artillery practice. It was the first day of the hunt.

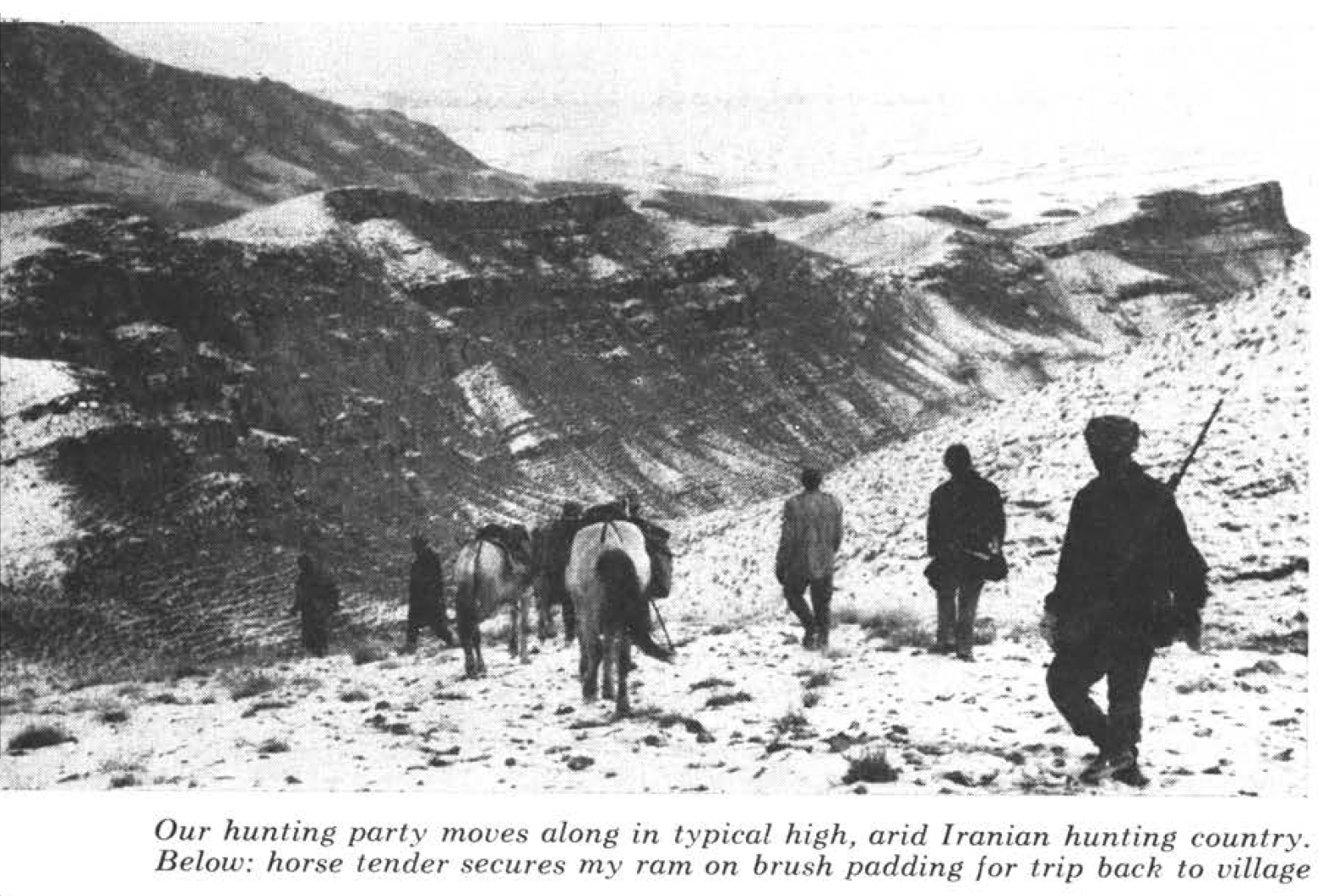

That morning Fred, his guide Manouchehr Abdallahian, and the rest of Fred’s hunting party had gone in pursuit of Armenian sheep. My guide Hooshang Bakhtiar and I tried for ibex. Besides Hooshang and myself, six other men were in my party: a government game warden, a husky young fellow in his mid-teens, a grizzled veteran of the mountains whose age lay somewhere between 45 and 75, and three horse tenders. The ages of the older men were hard to determine. The harsh life of the northern mountains may make young men look old.

Just before setting foot on the ledge, I took a picture of the narrow path and the steep drop so there would be a record of where I met my end.

The warden was a tall hawk-faced chap who sported a savage-looking moustache. He took great pride in his khaki uniform and the social status it proclaimed. Like many Iranians, he was a devoted cigarette smoker and always had a long ivory cigarette holder clamped between his teeth.

The old man was my gun bearer, I guessed, but since I almost always carried my rifle myself, he designated himself as my guardian and did a good job of it. Whenever I felt myself slipping backward on a steep, snow-covered slope or got caught among loose rocks, he was always there to help. He encouraged me with Turkish phrases and a warm smile, his six or eight remaining teeth lending character to his craggy grin.

The teen-ager was the son of another game warden. He carried my cameras, the lunch, and an armload of fire-blackened tea kettles. Weighted down as he was, and clad only in low-top shoes and a thin jacket, he galloped through the snowdrifts like a caribou, his face glowing and his black eyes snapping with enthusiasm. That lad is a born hunter, and he will be a fine guide.

I never understood just what the three other men were supposed to do. We had rented thin, railbacked horses from them, and perhaps they came along to see that we didn’t mistreat the horses. Maybe they merely wanted to watch an American hunt ibex.

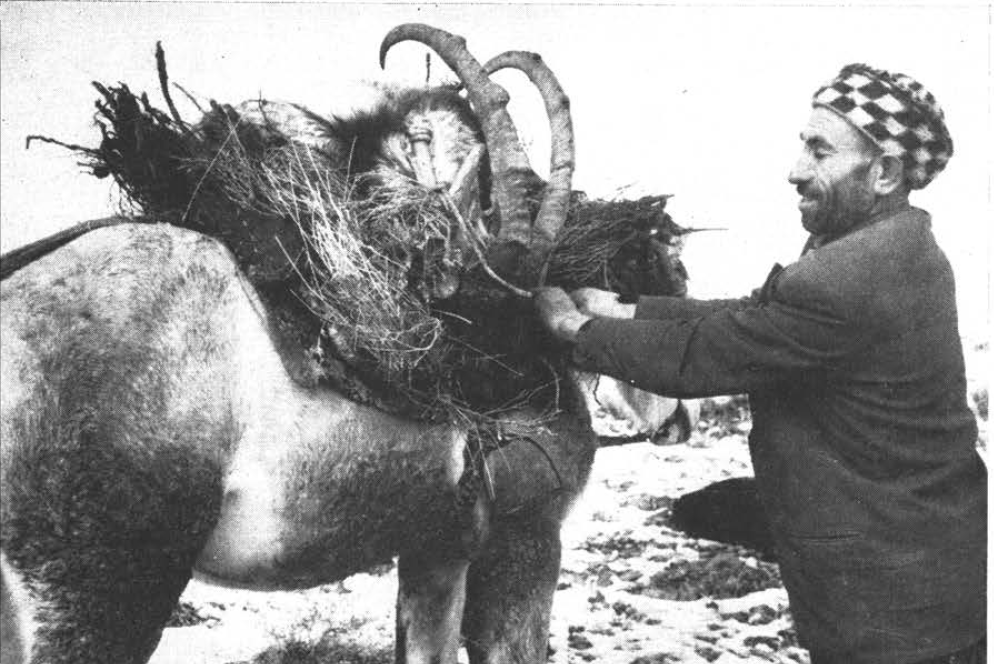

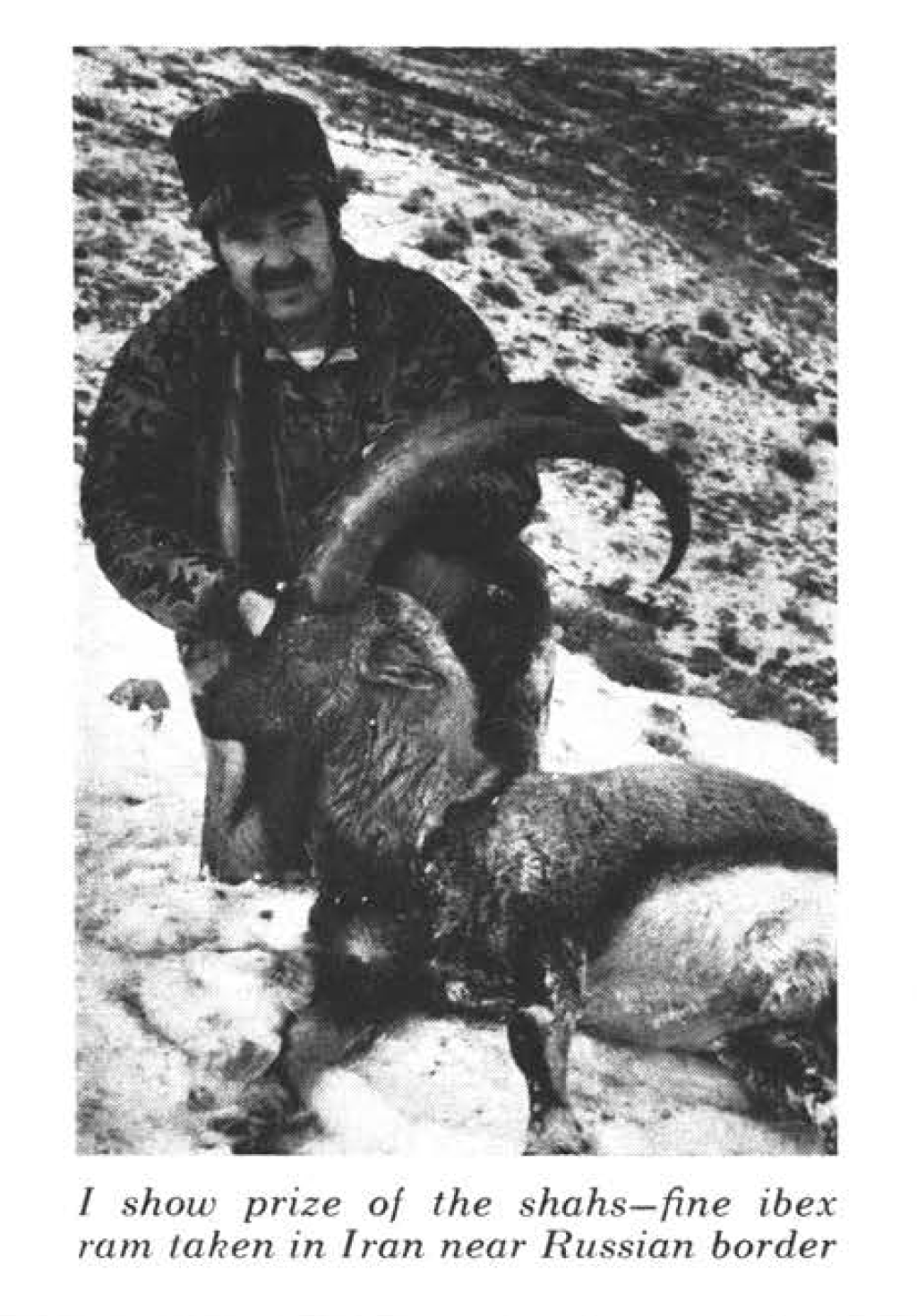

After leaving the mud-walled village where we were headquartered, we had skirted a range of almost vertical cliffs where the mountain-dwelling ibex makes his home. The ibex is a goatlike creature that weighs about 200 pounds and wears a rather nondescript coat of coarse, grizzled hair. All in all, he is not especially impressive — until you see a ram with good horns. Then your heart skips a beat. All out of proportion to his body size, the male ibex’s horns sweep up and back and end in a down-curving curl that becomes more pronounced as they grow longer.

Gold effigies of the ibex have been found in the ancient groves of Persian kings. If the real animal did not exist in modern times, these statuettes would inevitably be mistaken for representations of a mythological beast. The horns are unbelievable.

Within two hours after an early-morning start, we spotted a small band of ibex peering down at us from a ledge high in the cliffs. The climb looked impossible, but the Iranians were not impressed by the steepness or the height of the cliffs. After circling a quarter of the way around the mountain, we launched an assault straight up a steep slope. The grade was about 45° in the easy places; 60° was closer to the average. I know because I could often stand erect and extend my arms straight before me to touch the hillside.

The mountain was flat on top. After we circled around to the place where the ibex had been spotted earlier, we arrived just in time to see them scamper up a steep, rock-strewn draw. The animals hightailed to a higher elevation on the rim. That seemed something of a blessing because the undulating plateau would allow a less-exhausting and safer stalk than would have been possible on the cliffs.

The plateau was about a mile and a quarter wide, and the southern rim tilted up a few hundred feet higher than the northern rim. Predictably the ibex had headed for the highest part. Hooshang judged that they would drop off the rim and then circle back around the mountain. Wanting to save me a hard climb, he advised me to go with the warden to the lower rim and watch for the ibex to come around. Just to make sure we didn’t lose them, Hooshang would climb to the high southern rim and keep an eye out while the game warden, the old man, and I went in the opposite direction.

When we reached the low rim, the warden peeked over the edge and then quickly dropped to his knees behind a low bush. He motioned for me to get down too. After crawling up to where he was hidden, I saw a grassy bench about 100 feet below our position. It was some 200 yards wide and sloped gently downward before it dropped off.

On the outer edge of the bench was another herd of ibex — at least 25. Some were grazing among the rocks; others were lying down and grinding their cuds in contentment. The closer ones were about 300 yards out, a fairly long shot at so small a target.

I had sighted my rifle in for just that kind of shooting. The rifle was a Model 70 Winchester with a custom stock and barrel. It was chambered for the .280 Remington cartridge, and I had sighted it in to be dead on at 300 yards. My load was 57 grains of No. 4350 powder behind a 140-grain Nosier bullet. Fred Huntington had also brought a .280 rifle and was using an identical load. We figured that was a smart move in case either of us ran short of ammunition. Back at the village we had test-fired our rifles, and I was quite sure mine was still correctly sighted.

I therefore figured that I could put a bullet into an ibex’s powerplant without too much difficulty, even at fairly long range. There was a problem, though. Which ibex? Three or four rams carried horns noticeably larger than those of the others, but without Hooshang to advise me I couldn’t tell if they were of trophy quality.

The game warden spoke no English, but he evidently had strong ideas on the matter and began gesturing and beckoning me to shoot. He squeezed an imaginary trigger time after time and didn’t seem to care which ram I shot.

Hoping for some guidance, I looked over my shoulder at the old mountaineer to see if he had any ideas. To make my predicament plain to him I pointed at a few of the better rams and offered him my binoculars to show that I wanted him to look the herd over for a really good trophy. He simply gave me his gap-toothed smile, politely waved the glasses away, and then gazed off into space. He didn’t want to offend the game warden, but he seemed to be silently indicating that none of the animals was good enough to shoot. That was all I needed. I put my rifle aside to indicate that I would not shoot.

The game warden harangued me for a while in Iranian and then switched to Turkish. Finally he seemed to decide that anyone who couldn’t understand either language must be an imbecile, and he went off waving his hands and grinding his cigarette holder between his teeth.

About 45 minutes later our party regrouped on a low saddle beyond the grassy bench where we’d been watching the ibex. Hooshang said that the small band that he had been trailing included a ram with very good horns but that the ram was very wary and would be difficult to stalk. The herd, he advised, had gone onto the next mountain. All we could do for the time being was stay fairly close until they calmed down enough for a serious stalk.

Two hours later we were on top of the next mountain. The herd had bedded down on a sharply angling shelf below us. The ibex were 600 to 800 yards away, but there was a rock outcropping midway between us and the herd. That outcropping afforded excellent cover from which to shoot. I told Hooshang that if he could get me there, I could handle things. Getting there, however, would mean crossing about 400 yards of open ground. If we headed straight down toward the outcropping, the rams would surely spot us and vanish.

The game warden saved the day. To him the terrain was as familiar as the mouthpiece of his cigarette holder. When Hooshang told him that I wanted to shoot from the outcropping, he grinned and motioned us to follow him. The rocks, he told Hooshang, were part of a backbone that ran around to the back side of the mountain. We would drop down the backside, Hooshang translated, and circle around to where the backbone began. Then we would follow along behind the outcropping until I found a good place to shoot. It sounded too easy. It was.

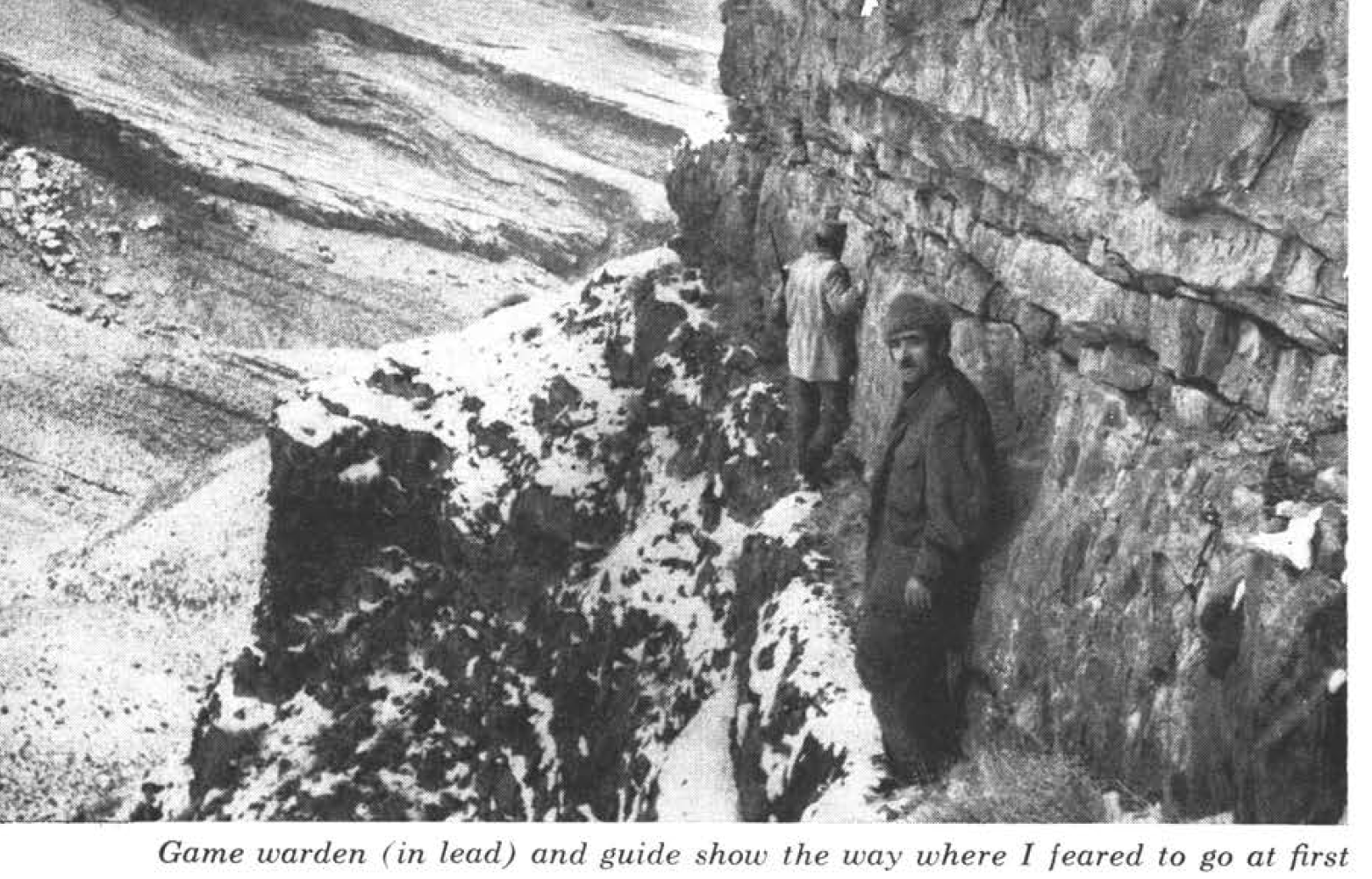

About halfway down the other side of the mountain, the steep slope gave way to a precipice. It was impassable except for a tilted, snow-covered ledge that snaked down the sheer wall.

The game warden strolled out along the ledge as casually as a man walking in his own garden, and Hooshang was about to do likewise when I told him to wait a moment. I wanted to discuss an alternate route.

With a sweep of his hand toward the chasm, Hooshang told me that the only other way was to go down to the gorge below us and then reclimb the mountain. That would take hours, he said, and the route along the ledge would take only minutes. To him the ledge was the only way, and the game warden thought my apprehension was a big joke. He grinned merrily, cocked his cigarette holder at a rakish angle, and, to show how unconcerned he was, offered to carry my rifle. I accepted.

Just before setting foot on the ledge, I took a picture of the narrow path and the steep drop so there would be a record of where I met my end.

As it turned out, it wasn’t as bad as I had feared. Just as the warden had promised, we quickly reached the long outcropping that curved around the mountain toward the ibex. I soon found a low shelflike rock to use as a shooting bench and placed my thick woolly cap on it in lieu of a sandbag. Then I settled the crosshairs of my 6X Leupold scope high on the chest of the biggest ibex. He was quartering toward me, dropping his head now and then to snatch a mouthful of whatever it is ibex eat in those barren areas. After each bite he nervously jerked erect to look for danger. Most of his buddies were blackish-brown except for their grayish undersides. The old fellow was gray farther up on his sides than the others and had a grayish patch running up his chest onto his throat.

His horns were noticeably thicker at the base than those of the other rams, and the outer tips tucked back under in a more-complete curl.

His horns were noticeably thicker at the base than those of the other rams, and the outer tips tucked back under in a more-complete curl. Hooshang whispered that the horns weren’t of record quality but that they were very good. That was all the advice I needed. My rifle rest was so solid that the crosshairs were virtually motionless when I pressed the trigger.

I was so certain the shot had been good that I ejected the cast with careless slowness while I scanned the ground for the prostrate form. The ibex wasn’t there.

“Shoot again! Shoot again — they’re running!” yelled Hooshang.

Had I missed? I couldn’t believe it. Completely bewildered and thoroughly rattled, I slammed the bolt home and swung the crosshairs ahead of a running ram, but I didn’t fire. I didn’t want to shoot at another ibex while there was any chance the first one had been hit, or was I seeing the first one through my scope again?

“Too bad — they are all gone,” Hooshang said.

“That first shot looked good,” I told him. “Are you sure he wasn’t hit?”

“No, he ran away very fast. You did not hit,” Hooshang answered. “It is getting late now. We will eat and start back to the village. Tomorrow we will try again.”

The old man, the boy, and the horse handlers were silent. It had been a long cold morning of difficult hiking and climbing. We had made a great stalk, and I had missed the shot. There was nothing more to say.

After the tea things had been gathered up we started down the hill in single file. I brought up the rear. We followed the route the ibex had taken, and just as the game warden dropped over the down-slope edge of the bench he let out a shout and ran downhill. At first I didn’t understand, but then the others were charging downhill and laughing and shouting. Hooshang slapped me on the back and said: “Come see. Come see.”

The big ibex lay on his side just below the brow of the hill. He was stone dead, a bullet hole through his heart. We had lunched not more than 100 yards from where he had fallen.

“That was a very good shot,” Hooshang told me with an enormous grin. “We are all very proud of you.”

Read Next: Carmichel in Australia: Charged by a Backwater Buffalo

The old man smiled, the boy whooped with unrestrained delight, and the warden, cigarette holder at a jaunty angle, ordered the others to load the ibex onto a horse. In his mind he was already savoring a broiled steak from my ram.

The sun was dipping low, and a cold wind began to sweep down out of Russia as we made our way off the mountain, but I felt very warm and very happy. I looked forward to telling Fred Huntington about my adventure. But he had been adventuring too. That’s another story.

The post Carmichel in the Middle East: Risking Our Lives to Hunt Iranian Ibex appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/carmichel-ibex-iran/