Breach or Die: It’s Time to Free the Lower Snake River and Save Idaho’s Wild Salmon

On a hillside above the Salmon River, Kyle Smith, his setter, and I stood there and panted. Still catching our breath from the climb, we looked down to see a fish break the water’s surface. The big Chinook rolled in a deep pool, a fine place to rest during her long trip home from the Pacific. Swimming more than 500 miles up the Columbia and Snake Rivers before taking a left up the Salmon, this fish dodged predators, avoided gillnets, and fought through walls of concrete to carry the next generation upstream.

We were pulled away from the scene when Sadie got birdy, and we followed her down a steep slope through broken basalt and cheatgrass. The dog went on point, a covey flushed downhill, and Smith dropped a chukar out of the sky.

Back at the water’s edge, we traded shotguns for fishing rods and hopped into drift boats. The guides rowed down to where the fish had rolled and we tossed out our plugs, using the boats to pull them back and forth across the pool. Minutes later, Smith hooked a fish. He landed the 12-pound hen in the shallows, her silvery sides reflecting a tinge of maroon in the sunlight.

It was the heaviest fish we caught during our week-long float down the Salmon, but her value couldn’t be measured in poundage alone. She’s a symbol of what we’ve lost and everything we stand to regain. Because although this river still holds some of its namesake fish, its once prolific runs of wild salmon and steelhead are on life support.

Historically, out of the roughly 10 to 16 million fish that would return to the Columbia River Basin each year, over 2 million would swim up the Snake and its tributaries to spawn. This included sockeye salmon, coho (or silver) salmon, Chinook (or king) salmon, and steelhead (a rainbow trout that migrates to the ocean and back).

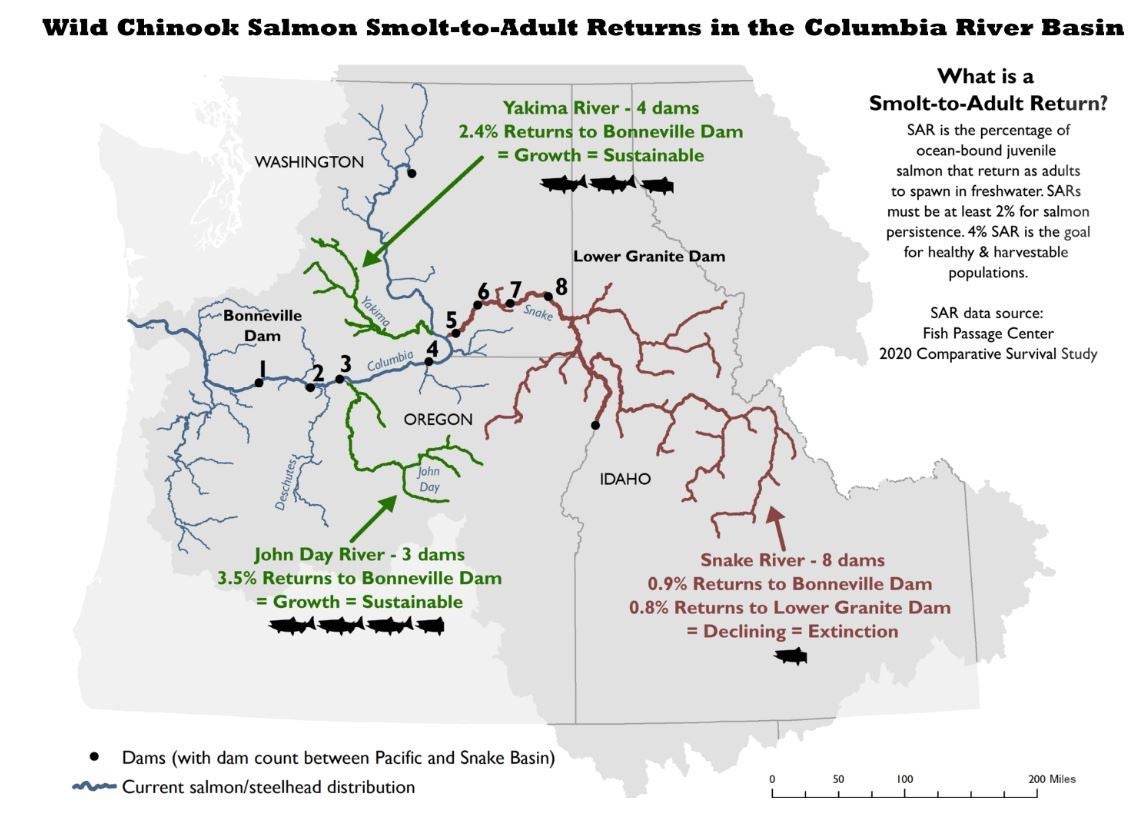

Today, these fish are returning at less than two percent of their historical abundance as their ancestral migration route is choked by four aging dams that are getting harder and harder to justify. Every one of the anadromous fish stocks native to the watershed is now endangered or threatened, while some runs have collapsed altogether.

These hardy sea-goers are suffering on a global scale, but the fish that return to the Snake River Basin are in a unique position to be recovered. All they need is their river back.

Down in the Canyon

On a starry night in late September, after going one for two on steelhead that day, we sat around a campfire near the mouth of Billy Creek. Our group might have seemed an odd cast of characters anywhere else. But on this particular beach, it was only natural for a trial lawyer, a photographer, a country and Western drummer, a writer, a city councilman, a campaign organizer, a young river guide, and a 72-year-old ski bum to share camp. Our cups full and our bellies stretched, we wiggled our toes in the sugar sand while bull elk bugled on the ridge tops.

Across the fire from me sat Roy Akins, the veteran guide who led our crew down the river his life revolves around. He read aloud from a book of poems written by an old fisherman.

…Lookin’ back on it feels like so long now,

I did good for havin’ no plan.

Well I’ve got it made and I’ll never trade

The life of a Riverman…

A sportsman with a ponytail and a mystical side, Akins was cut from the same cloth as the legendary boatmen who pioneered these runs in wooden dories. He names all his favorite lures and has a keen eye for agates, which he carries around in his pockets. The creases on his face are from squinting into the sun and sleeping in the rain, but the deepest lines seem carved by laughter.

Over the course of our float down the Salmon, Akins shared most everything he knew about the river’s past and the pains of its present. Every stretch held a story. Early in our journey, we anchored our boats at Big Rock Creek, which has what’s arguably the longest tale.

Now the site of Cooper’s Ferry, this side canyon was home to an ancient village of the Nez Perce, who call themselves the Nimiipuu, or “the people.” It’s now considered the oldest human-inhabited site in the Americas, and the most recent archaeological dig determined people have lived on this stretch of the Salmon for at least 16,000 years.

The culture that flourished here was built around the first foods that sustained it. Chief among these were the salmon, which gave themselves to the people as they returned to the river each year to spawn and die. In completing their lifecycle, these fat, oily fish fed not only humans, but every other being in the river corridor, too.

“The Nez Perce Tribe, Nimiipuu,” says Nez Perce tribal chairman Shannon Wheeler, “has a cultural and spiritual connection to the land, water and nàcox—the salmon.”

The Case for Breaching the Snake River Dams

The Columbia River system was once the most productive salmon and steelhead fishery in the world. This included not only the Big River, but also the hundreds of tributary streams that form a giant basin encompassing most of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, along with parts of British Columbia, Nevada, Wyoming, and Montana. The mightiest of these tributaries, in terms of the volume of water and salmon it carried, was the Snake.

The Snake River’s spring and summer Chinook run, for example, used to number around 1 million wild fish annually. This year, fisheries managers are estimating a return of around 7,500. And if their most dire predictions come true, these fish could wink out within the next 20 years.

Human intervention is mostly to blame. First, we caught, killed, and canned too many. Commercial fishing boomed on the Columbia River during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when salmon harvests peaked at around 42 million pounds per year. By the time the first federal dam was built in 1938, engineers and government officials had convinced themselves that with enough human engineering, we could have salmon and steelhead without rivers.

The more than 470 dams that were built on the Columbia, Snake, and their tributaries have cut off access to more than half of the spawning habitat that once existed there. The upper third of the Columbia is now devoid of migratory fish, and a wild salmon hasn’t been seen in Nevada waters since the 1930s.

The best remaining habitat is found on the high-elevation, cold-water streams like the Salmon that pour into the Snake. As we look toward a warmer future, fisheries biologists see these free-flowing rivers as the last stronghold for anadromous fish in the lower 48.

Standing between the Pacific Ocean and this salmon Shangri-lah are eight large dams controlled by the federal government—four of which were built on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington during the 1960s and 70s. And the declines in fish returns we’ve seen over the last half century have proven that eight dams are just four too many.

“The negative impacts of [federal] dams and their reservoirs on salmon survival are clear and unequivocal,” wrote 68 leading fisheries scientists in 2021. “The survival problems of various ESA-listed salmon and steelhead species in the Columbia Basin cannot be solved without removing four dams on the Lower Snake River. These four dams must be removed to not only avoid extinction, but also to restore abundant salmon runs.”

A report issued by NOAA Fisheries last year echoes these conclusions. The authors refer to dam breaching as the “centerpiece action” in restoring Snake River fish stocks, and they call “for bold and immediate action.”

Removing the dams won’t solve all their problems, as the myriad factors plaguing Pacific salmonids extend beyond their home rivers. Poor ocean conditions are also impacting fish populations, and one researcher contends that until we can fully diagnose problems in the Pacific, breaching the Snake River dams should be a secondary concern.

“It’s a problem of poor marine survival. The problems caused by the dams are small compared to the very large declines in ocean survival that nobody knows how to address,” says CEO of Kintama Research David Welch. “The question now is: If you take the dams out, is the productivity of those populations going to go up the way proponents want? And my answer is: I don’t believe so.”

Many experts struggle with Welch’s conclusions, pointing out that his 2020 study on coast-wide declines was funded by the same behemoth utility company that benefits the most from the Lower Four Dams. (Welch acknowledges this and stands by his findings, which he says were not influenced by his funding.) Other scientists don’t doubt that ocean conditions are having serious effects on fish, but they also believe that the best way to keep populations viable is by pulling the levers under our control.

Freeing the Lower Snake would benefit more than just the fish: It would expose the roughly 14,000 acres of big-game and bird habitat that’s now underwater—most of which would be public land. It would also restore around 140 river miles, uncovering whitewater rapids and cultural sites, and effectively re-opening one of the West’s most accessible float trips.

A Moral Dilemma in Dam Breaching

As the calls for dam breaching have turned to shouts, the campaign has been championed by a growing army of anglers, hunters, river runners, tribes, and conservation groups.

“Those of us who hunt and fish, we consider ourselves to be resilient and resourceful,” says Liz Hamilton, executive director of the Northwest Sportfishing Industry Association. “And I don’t think anything says ‘resilience’ like a creature that goes out 600 to 900 miles to the ocean, finds its way back, and then gives itself up for the next generation to succeed. It’s a moral issue, for those of us who live the hunting and fishing life, to allow an [Idaho] steelhead or a spring Chinook to go extinct.”

This dilemma is also a political one. The Lower Four Snake River Dams are federally owned and operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which means that breaching them would require an act of Congress. And since the dams provide several benefits to our modern, energy-hungry society, the notion of dam-busting pits fish and river advocates against the dam’s supporters.

These include the farmers who ship their wheat in barges down the Snake, and the growers who irrigate with water pulled from the reservoirs. But the loudest (and wealthiest) voice representing the pro-dam crowd is the Bonneville Power Administration, which purchases the hydroelectric power that’s generated by the four dams. This accounts for roughly 1,000 megawatts in a normal year, or roughly 4 percent of all the electricity generated in the Pacific Northwest.

As the executive director for Northwest River Partners, Kurt Miller advocates for the region’s community-owned utilities, which get most of their electricity from hydroelectric dams. He says the electricity generated by the Lower Four Snake River Dams helps stabilize the power grid, and points to research that warns against sacrificing any of our renewable energy sources.

“If you’re really serious about achieving a decarbonized grid, then you need to keep your hydropower resources,” Miller says. “And decarbonization laws have made it so that the Lower Four Snake River Dams are essential to meeting those goals.”

The pro-breaching crowd says otherwise—and that concerns around grid reliability have typically been blown out of proportion by those who profit or otherwise benefit from the dams. They also point out that the proposal for breaching would replace every benefit provided by the structures before they’re removed.

For irrigators, this would mean renovating their systems so they could reach a free-flowing Snake. Meanwhile, the grain growers who’ve benefited from subsidized barging in recent decades would rely on trains and trucks to ship their harvests, just as their neighbors do elsewhere in the inland Northwest. Replacing the dams’ electricity with other renewable sources will take effort, but we’re already well on our way. Batteries are getting more affordable, and investor-owned utilities in the region are planning to bring 10,000 megawatts worth of wind and solar projects into the grid by 2030, according to a report from the Northwest Energy Coalition.

“The fact is that we can replace every single social and economic benefit provided by the Lower Four Snake River Dams,” says Trout Unlimited CEO Chris Wood. “We can replace the power, we can replace the water, we can replace the transportation, we can replace all those benefits. Except the fish need a river. They just need a river.”

Itching to Catch a Steelhead

After studying the long, glassy run below our first night’s camp, a few of us just had to swing flies through it. We grabbed two-handed rods and followed each other down the inside bend, working the run from top to bottom with nary a tug. As we shed our waders back at the tents, Akins, a devoted plug puller, told us we’d be able to fish the run “properly” before we left the following day.

“Besides, fish laugh at flies,” he added with a smile.

In the morning, Akins’ right-hand guide Ben Brault rowed us through the meat of the tailout. As he pulled on the oars to keep the plugs working, I watched the rod tips twitch and bounce and fought my own internal battle between hopefulness and fishless despair. Then it happened.

I heard the reel’s clicker scream before I saw the rod go down, and I fought the urge to set the hook as I reeled tight to the fish. Way out in front of the boat, the steelhead jumped twice as it took off running for the rapid below. Brault hauled on the oars while I pulled sideways on the rod, and we turned the fish back upriver.

When we eventually brought it to the net, I saw the fish was slightly colored up from the time it had already spent in fresh water. It wasn’t one of the giant B-run steelies that Idaho rivers are famous for, and it had a clipped adipose fin, which told us it was a hatchery fish and not a wild one.

But it was still a steelhead—the first I’d caught in years and Brault’s first of the season. As I held the fish and looked into its wandering eye, I felt I’d been given a rare and remarkable gift.

Covenants, Treaties, and Broken Promises

The government officials who green-lit the construction of four dams along the lower Snake were keenly aware of the connection that indigenous peoples had with Pacific salmon. They also suspected the dams might impact the agreement they made with the tribes more than a century prior.

This agreement, known as the Treaty of 1855, required the Nez Perce and other sovereign nations to cede millions of acres to the U.S. government under the sole condition that they would retain the rights to hunt and fish in “their usual and accustomed places.” Those rights were severely eroded, however, when the government’s dams went in, burying some of their favorite fishing holes underneath 40 feet of water.

“Preserving and restoring the salmon population is a high priority for our people, to ensure the survival of not only our culture, but our identity and way of life,” chairman Wheeler says. “It is our ancient covenant to the salmon that gave up so much for us.”

It’s now been 48 years since we severed Idaho’s connection to the Pacific by completing the last of the Lower Four Snake River Dams. As we’ve watched these fish disappear, we’ve paid a fortune to compensate for the dams’ interference.

Tribes and government agencies have built hatcheries to compensate for the loss of wild fish, but these facilities have largely failed to meet their goals. The dam’s operators have also tried replacing the river’s current with buckets, trucks, pipes, and barges. After going through countless lawsuits and spending $17 billion in taxpayer dollars, these mitigation efforts haven’t been enough to stem population declines.

That’s because the dams harm migratory fish in several ways. Fish ladders help the adults jump the hurdles, but they aren’t 100 percent effective, and the big, spinning turbines occasionally turn some juveniles into mincemeat. They’ve also decimated stocks of less glamorous native fish like Pacific lamprey and white sturgeon, which are unable to pass through the fish ladders.

But it’s not just the dams that kill fish. The real killers are the slackwater reservoirs backed up behind them.

Sea-going salmonids are most vulnerable when they make their downriver trip to the ocean—known as the outmigration. In the pre-dam era, their springtime journey from the Idaho border to the Columbia River estuary would take about two to four days, according to Jay Hesse, a researcher and fisheries manager for the Nez Perce Tribe who’s spent the last five years studying the relationship between dams and salmon. It now takes juvenile fish between 10 and 30 days to make the trip, he says.

“Now, out of that stretch that’s 465 miles long, 324 miles of it are impounded reservoirs, so it’s no longer a free-flowing river,” Hesse explains. “Think about it this way. If you’re starting a road trip and you think it’s going to be a three-day trip, but it takes you 30, you’re not gonna have enough gas in the tank to make it.”

The 324-mile slog has become even more perilous as the sluggish reservoirs have warmed. This brings an influx of warm-water species like smallmouth bass and walleye to the lakes, where they form chow lines and feast on smolts. Terns, cormorants, and other birds take advantage as well, dive-bombing the fish from above.

The Sockeye Swim

Akins knows all about this hellish journey. After all, he’s one of the only people who’s experienced it firsthand.

Born one year after the last of the Lower Four Dams went in, Akins never got to see a free-flowing Snake. What he did witness during his formative years were the huge declines in fish numbers across his home state. These crashes peaked during the early 1990s and were embodied by the tale of Lonesome Larry, the only sockeye that returned to Redfish Lake in 1992.

At that time, most people blamed everything but the dams for flagging salmon runs. They pointed to poor habitat in headwater streams and commercial boats along the coast. Others, like Akins, couldn’t see how the dams weren’t having an effect.

“Us guys who love the river, we wanted to try and help spread the word because we felt that there was a smokescreen,” Akins says. “We truly believed there was more to the story, and it didn’t take much research to figure out that the Lower Four Dams were killing a huge percentage of our outmigrating smolts every year.”

To prove their point, Akins and three friends decided to imitate the outmigration by swimming all the way from the Salmon River headwaters through Lower Granite, the uppermost of the four dams. On July 1, 1995, the men started their 580-mile relay swim from Redfish Lake Creek to Lewiston. It would take them 31 days to complete.

“When we started, life was pretty easy on the Salmon River. We made incredible mileage, up to 28 miles a day. We had to swim in some of the really nasty rapids, but other than that it was easy traveling. At times we just floated on our backs and rode the current,” Akins recalls. “But when we hit that dead water above Lower Granite, boy, everything changed. We had to freestyle swim with the wind in our face, with the waves hitting our biceps every time we threw our arms forward.

“It was the stench that stuck with us the most, from all the toxins backed up behind the reservoir,” he says. “It smelled like death.”

Along the way, the swimmers and their support crew would stop in towns to hand out pamphlets. But the wet, bearded men were seen as “radical environmentalists,” and Akins remembers being waked by power boats as they struggled through the lake.

By the time they reached Lower Granite, however, they’d been joined by the Nez Perce, who ran alongside in dugout canoes and jetboats, cheering them on. Somehow, the swimmers convinced the Corps of Engineers to let them pass through the dam’s lock as long as they stayed with the tribe’s boats.

“The Corps guys said, ‘All right, you can stay in the water, but you have to be holding onto a boat with both hands.’ Which was great advice, because it about ripped our britches off when they dropped that lock,” Akins laughs. “But being with the tribe as they sang their prayers for the fish and beat on those drums. It gave us the sensation that the whole damn thing might come crumbling down while we were going through it.”

Turning the Slow Wheels of Congress

In the years since Akins’ epic swim, the campaign to breach the dams has moved along in fits and starts. There’s still a stigma of radical environmentalism that’s tied to dam-busting. And since the dams are located in rural, deeply red voting districts, it’s traditionally been a political non-starter.

That all changed in 2021, when a conservative senator from eastern Idaho announced his support for dam breaching. Sen. Mike Simpson (R-ID) was one of the last politicians anybody expected to back the idea, and his announcement jump-started a conversation.

“My staff and I approached this challenge with the idea that there must be a way to restore Idaho’s salmon and keep the Lower Four Snake River Dams,” Simpson says in a video explaining his Columbia Basin Initiative. “But in the end, we realized there is no viable path that can allow us to keep the dams in place.”

His $33 billion plan would give farmers, bargers, ports, the Bonneville Power Administration, and local communities the resources to make the transition while ending decades of ongoing litigation.

Washington Governor Jay Inslee and Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) followed with their own recommendation, which says “the status quo is not a responsible option.” Even more recently, the Biden Administration has thrown its weight behind the issue, acknowledging what river advocates have said all along: that federal dams on the lower Snake have “severely depleted fish populations” and undermined the core promises guaranteed in the Treaty of 1855.

To understand the benefits of dam breaching, consider Washington’s Elwha River. When the river’s two dams were removed in 2011, it was the biggest project of its kind in U.S. history. In the 12 years since, wild salmon and steelhead have returned there in higher numbers (and more quickly) than most people expected. This year, the Klallam Tribe held its first salmon season on the river in more than 100 years.

Proof That Dam Breaching Works

“We know the fish will come back,” Wood says. “Steelhead were functionally extinct [in the Elwha] for 106 years. And a couple years ago, we had a couple of our scientists go up and snorkel the stream. They found 600 spawning pairs of steelhead. So, the rainbow trout in the headwaters, they recovered their anadromy. They remembered.”

Director of government affairs for the Wild Salmon Center Jess Helsley says there’s no reason to believe that breaching the Snake River dams wouldn’t have similar effects.

Read Next: How a Dam Malfunction on the Madison River Nearly Wrecked a Blue-Ribbon Fishery

“These fish are proving to us time and time again that if we just simply give them the opportunity to go back to their home waters, they’re going to do it,” she says. “It harkens back to the tenacity of these fish. They’re displaying the same sort of drive and leadership that we need to see in the members of Congress right now.”

The other politicians representing the people and resources of the Northwest have mostly avoided taking a stance on the issue, however. Wood says “their silence has been deafening.”

Perhaps this is because they’ve never experienced the Salmon River in the fall, when the hills are alive with game and fish are rolling in the current.

On the final leg of our trip, as we approached the confluence with the Snake, we passed through a stretch called Blue Canyon. One of the deepest and most spectacular of all the river’s canyons, it was also the site of the only concrete wall that’s ever plugged the Salmon.

Sunbeam Dam was built by a mining company in 1910 to power the mine and a nearby mill. The company went broke within a year, but the derelict dam stayed and blocked all fish passage for the next 20 years or so. This blockage was cleared in 1933, when the dam was blown up at night by parties unknown. Although the story behind Sunbeam remains one of Idaho’s greater mysteries, most believe the dam-busters were local fishermen.

As we passed through the old Sunbeam site and Akins pointed to the chunks of rebar on the canyon walls, I listened to the echo of water running freely over rock. It sounded just like a river should.

The post Breach or Die: It’s Time to Free the Lower Snake River and Save Idaho’s Wild Salmon appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/conservation/free-the-lower-snake-save-idahos-wild-salmon/