An Inside Look at the Wildlife Lab That Ages 10,000 Animals Every Month

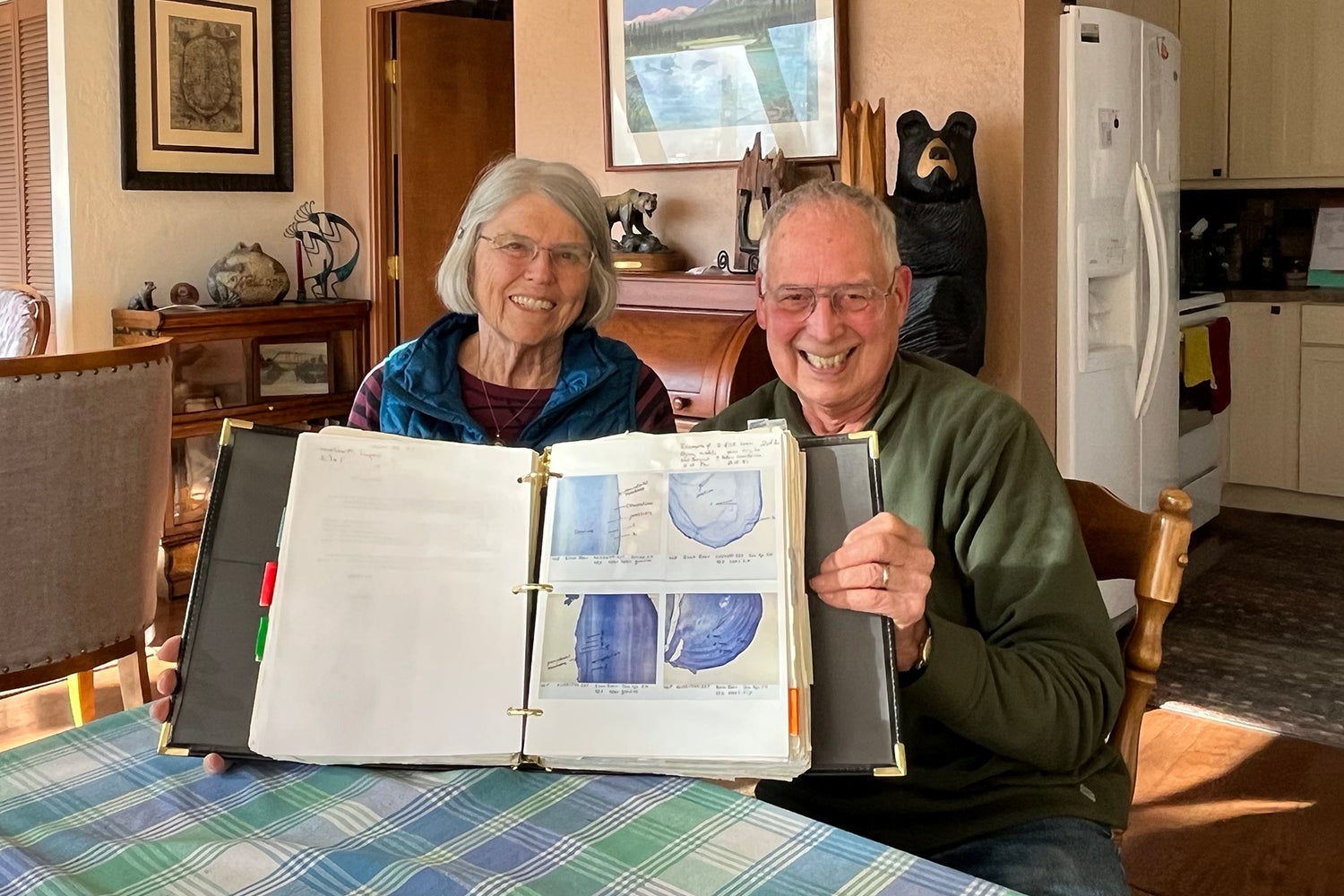

BEFORE MATSON’S LABORATORY was a standalone building on the outskirts of Bozeman with its own mailing address and parking lot, it was a run-down trailer parked next to Gary and Judy Matson’s house in Milltown, Montana. It had no bathroom, no heating or air conditioning, and no room for more than one person to work at a time. So when Gary finished setting decalcified black bear and bobcat teeth in delicate blocks of paraffin wax, he delivered them—bungee-corded to the back of his bicycle—to his lab interns for processing.

A lot about Matson’s Laboratory has changed since its trailer days, which started in 1969. First, the Matsons paid a guy named Rusty to haul the trailer away, watching the old beater eject pieces and parts as it bounced down the road. In 2014, they sold the lab to its current owners, who moved the business to Manhattan, Montana. But the express purpose of the lab—using a cross-section of a specially-prepared tooth root to determine a mammal’s age—hasn’t changed one iota. Except now, more state game agencies and biologists from around the world rely on their work than ever before.

The age data that Matson’s Laboratory collects from specimens (mostly teeth, but also the occasional reptile femur, amphibian toe, and narwhal tusk) provides wildlife biologists and managers with crucial insight into herd health, reproductive success, and potential roadblocks to meeting population goals for game species. For this reason, contracts with state and federal agencies have kept the lights on at the independently funded lab since the trailer days.

But over the years, more and more hunters have begun sending teeth from the bears, deer, elk, pronghorn, and other mammals they’ve harvested to the lab. In fact, Matson’s has received more hunter-harvested tooth submissions in 2023 than ever before, signaling either a growing awareness of the lab’s services or a growing curiosity among hunters—or both.

Cementum Annuli Analysis at Matson’s

In the lobby of Matson’s Lab, a mountain goat mount hangs over the front desk; in the corner, glass display cases house multiple skulls, some missing a top or bottom incisor. It’s clear this is a place where hunting and science overlap.

Lab owner Carolyn Nistler and manager A.J. Stephens oversee a team of eight other lab technicians. The 10-person staff processes between 10,000 and 12,000 teeth a month. There are certain proprietary processes the staff uses to manage such a high volume of submissions; those techniques are not pictured below, since Matson’s competes with other independent labs that do similar work.

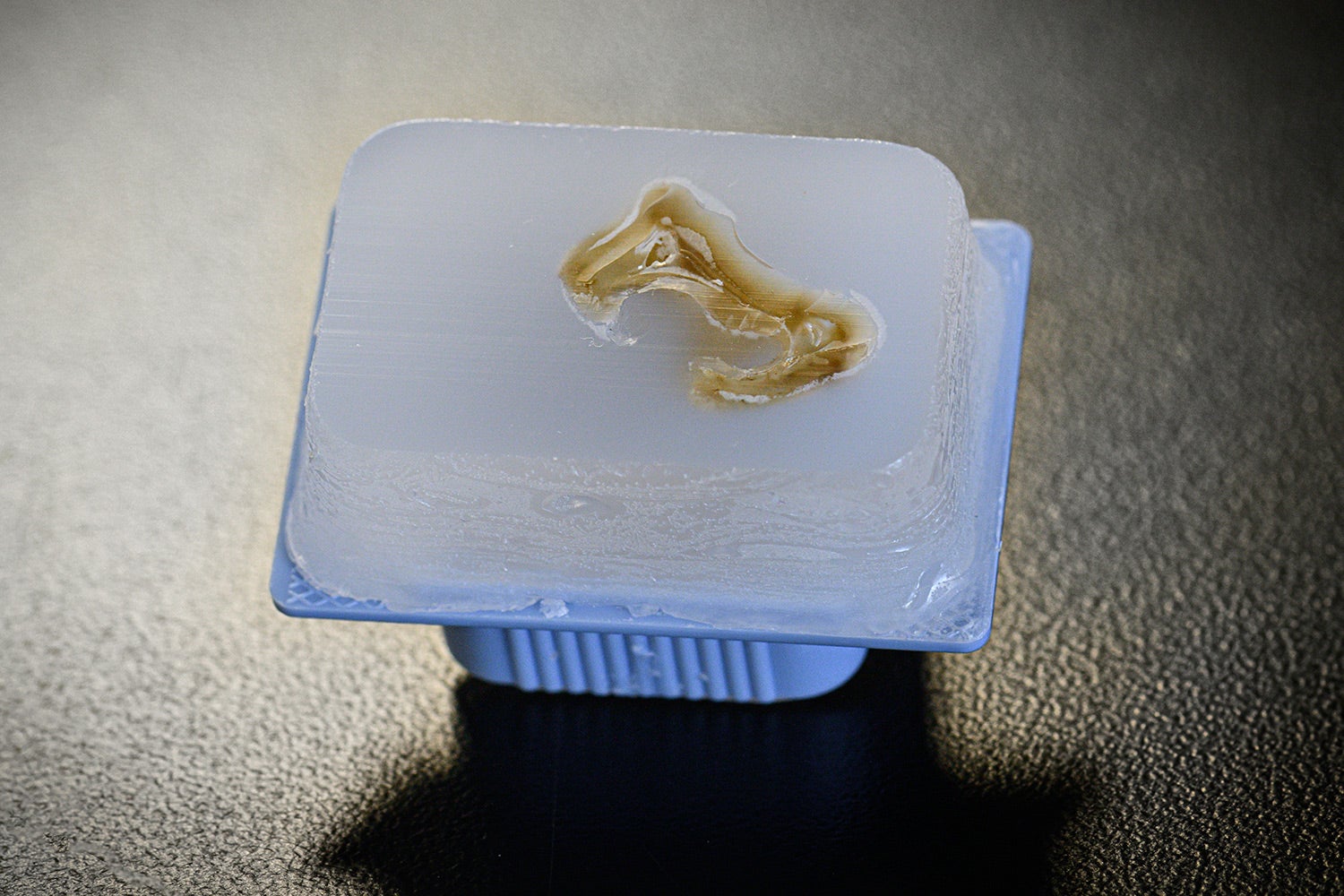

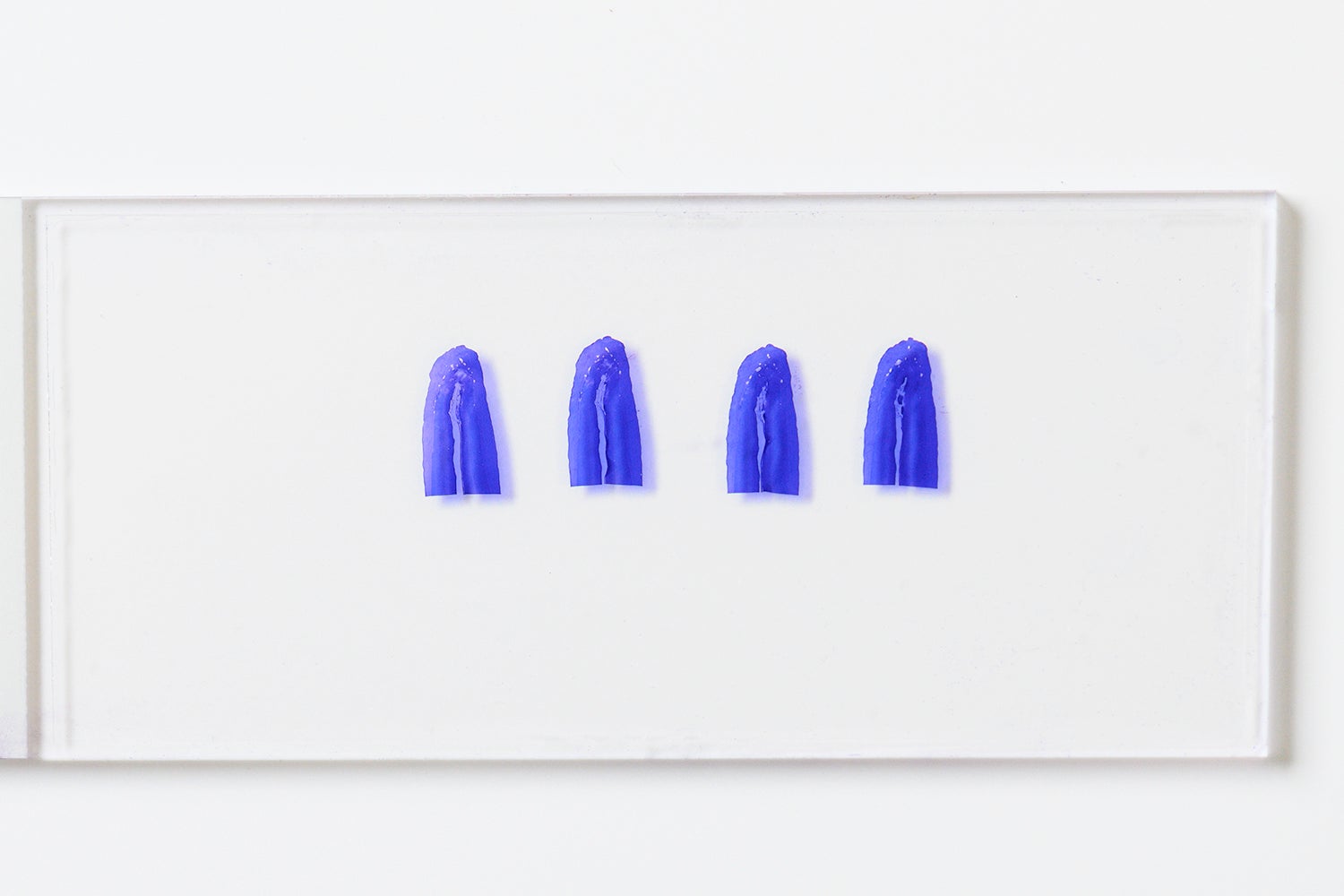

When one of the lab’s slides goes under a microscope, the ager zooms in on the long vertical edge of the tooth root. As animals age, the roots of their teeth gain a new layer of cementum, or calcified tissue, for every year they’re alive—not unlike rings on a tree.

As those layers stack up, they communicate more than just age. Tooth roots from black bear sows show the one-year-on, one-year-off pattern of their breeding cycle, Gary explains. In the years sows are pregnant, their teeth will grow a thick cementum layer from gaining so much weight. In the years that a sow births and nurses, the cementum layer is thin and scant, since the sow gives up so much energy and nourishment to support her cubs.

Cementum annuli analysis reveals signs of disease, malnutrition, and meager years in most animals. As an animal ages, the cementum layers become thinner, a sign that their bodily systems are slowing down. All this information is valuable to wildlife managers, according to Gary.

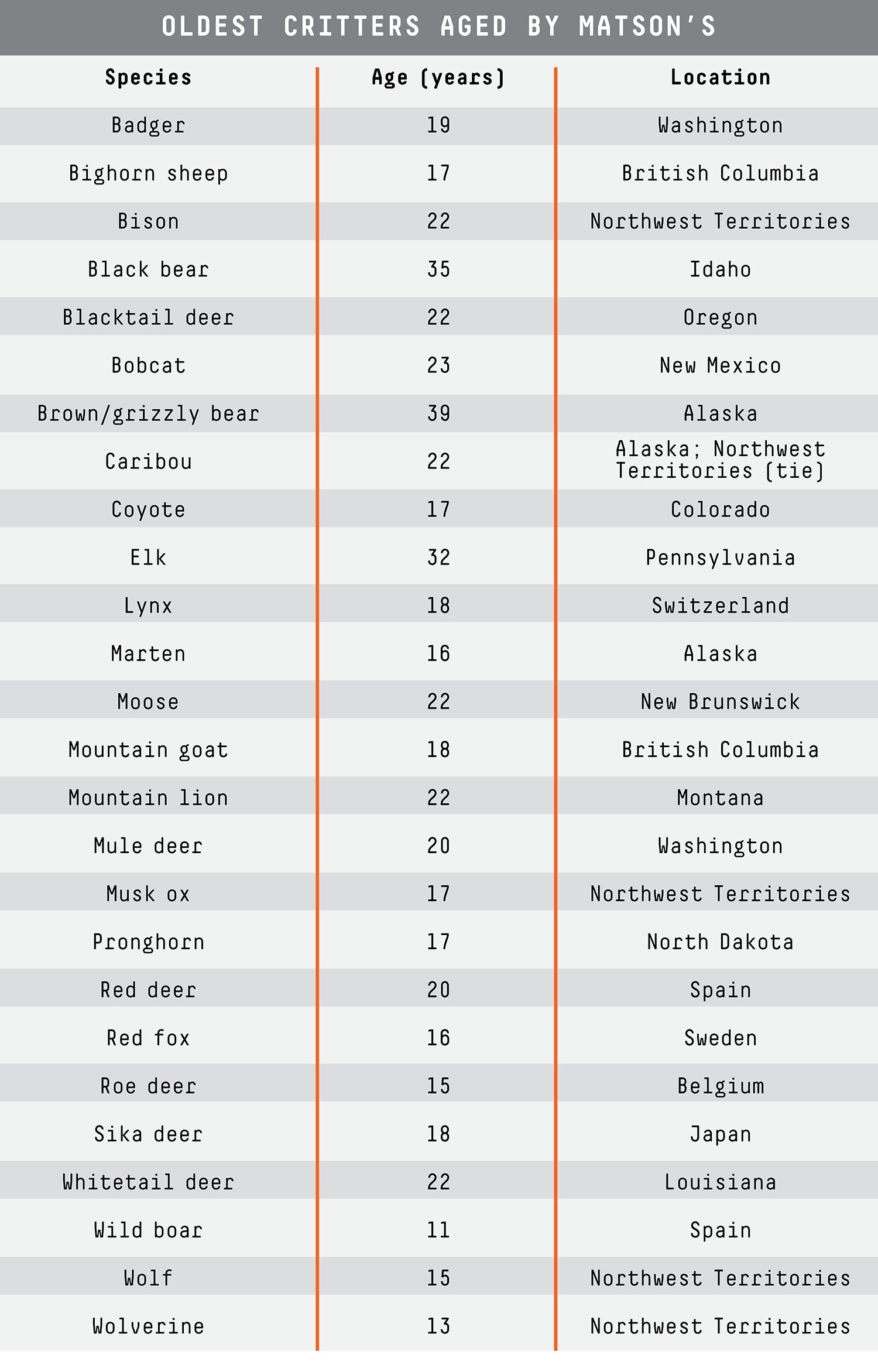

“The aging technique has stayed relevant,” Gary says. “Nobody has figured out a better, cheaper way to age animals. The lab is set up to handle hundreds of teeth every day. Agencies from all over, mostly the U.S. and Canada but also Europe and Japan, have monitored their populations using that age data.”

Lots of hunters have strategies for aging their favorite species, from judging body characteristics on the hoof to the outward appearance of a dead animal’s teeth. But that expertise takes time to build. Meanwhile, Matson’s boasts an extremely high level of accuracy in its cementum annuli analysis work. Lab techs at Matson’s have proven their technique is at least 85 percent accurate at correctly aging whitetail deer; more than 90 percent accurate at aging elk, mule deer, and black bears; and 96 percent accurate at aging moose (based on the percent of known-age teeth that analysts correctly in multiple blind tests.) Matson’s has successfully used the cementum aging process on every mammal species in North America, and their insight is helping satisfy the curiosity of hunters and the needs of wildlife managers all over the country.

How to Age a Tooth

Defeating Anti-Hunters with Tooth Aging

It took five years for the Matsons’ success to build. At first, they wanted to make microscope slides for college biology students. But that business turned out to be what Gary describes as a complete and utter failure. So they pivoted.

“The leader of the University of Montana Wildlife Research Unit … launched this method of aging grizzly bears,” Gary says. “They would go to Yellowstone National Park and immobilize a bear, pull a tooth, section it, and count the rings in the tooth to determine the bear’s age. One of my friends, a student working in the research unit, said we should try it. So we did some initial work and mimeographed a bunch of [advertising] postcards and sent them around to different wildlife agencies. Sure enough, orders started to trickle in.”

The Matsons’ first big order came from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The antihunting organization Defenders of Wildlife had accused CDFW of allowing bobcat overharvest; CDFW wanted proof that DOW’s allegations were inaccurate.

“Age structure is an indicator of how healthy the population is. So they used our lab to get evidence that the bobcats in California weren’t being overharvested,” Matson says. “That was the first time that we actually made a living from analyzing teeth. They sent us thousands of bobcat teeth. I had no idea there were so many people harvesting bobcats over there. So that made us not prosperous, but less unprosperous, and it just kind of built from that point.”

It soon became clear to the Matsons that wildlife agencies would always need help from the lab. As long as the agencies had enough funding, wildlife managers would reliably seek age data year after year to update species reports, set harvest quotas, and maintain an accurate view of overall species health. Gary points to black bear management in Pennsylvania as a key example.

“Every year, the [Pennsylvania Wildlife Commission] would send us 2,000 to 3,000 black bear teeth,” Gary says. “That made a stable economic platform for the lab to operate under, because all the other agencies did the same thing. So we didn’t deliberately set out to contribute to wildlife management. But the fact that it turned out that way was something that we felt very satisfied about.”

A New Surge in Clients

Nowadays, receiving tens of thousands of teeth every month from a global clientele is routine to Matson’s employees. What has taken the lab by surprise is the increased interest from hunters.

“I think our agency submissions are largely unchanged, but definitely among hunters the interest has gone up,” Nistler says. “Hunters want to know the ages of their animals, either out of sheer curiosity or because they want a hand in managing the resource on the lands that they hunt, whether it’s their own private land or a ranch or public land. I think it’s really cool.”

Stephens says the biggest year-over-year increase in hunter interest has been between last hunting season and this year’s.

“Every Monday, the mail lady needs to take two trips to get all the packages in,” he says. “We’re seeing more and more conservation-minded hunters who have an interest in that aspect of the animal, rather than just what it scored. They want to know its life history.”

Gary didn’t exactly love serving hunters in the early days. It’s not that he’s against hunting on principle, he says. It’s just that clients who sent in one or two teeth at a time paid much less than the bigger clients. Hunters couldn’t keep the lights on in the lab the way wildlife agencies from California, Pennsylvania, and overseas could.

Now Matson’s Lab now charges hunters a flat $75 for up to four tooth submissions, with an additional $5 fee for a digital certificate or $10 for a paper copy. Since hunters pay the same price to age one tooth as they would for four teeth, it’s easy to split the fee with a few buddies. After the fourth, each additional tooth costs $15; bulk pricing becomes available at 31 teeth. Depending on the species and the size of the tooth you send to Matson’s, you might also get the crown of the tooth back for a skull or mount. For example, elk and moose incisors and bobcat canines are big enough to preserve, while deer incisors and bear premolars are so small that the whole tooth is destroyed in the aging process.

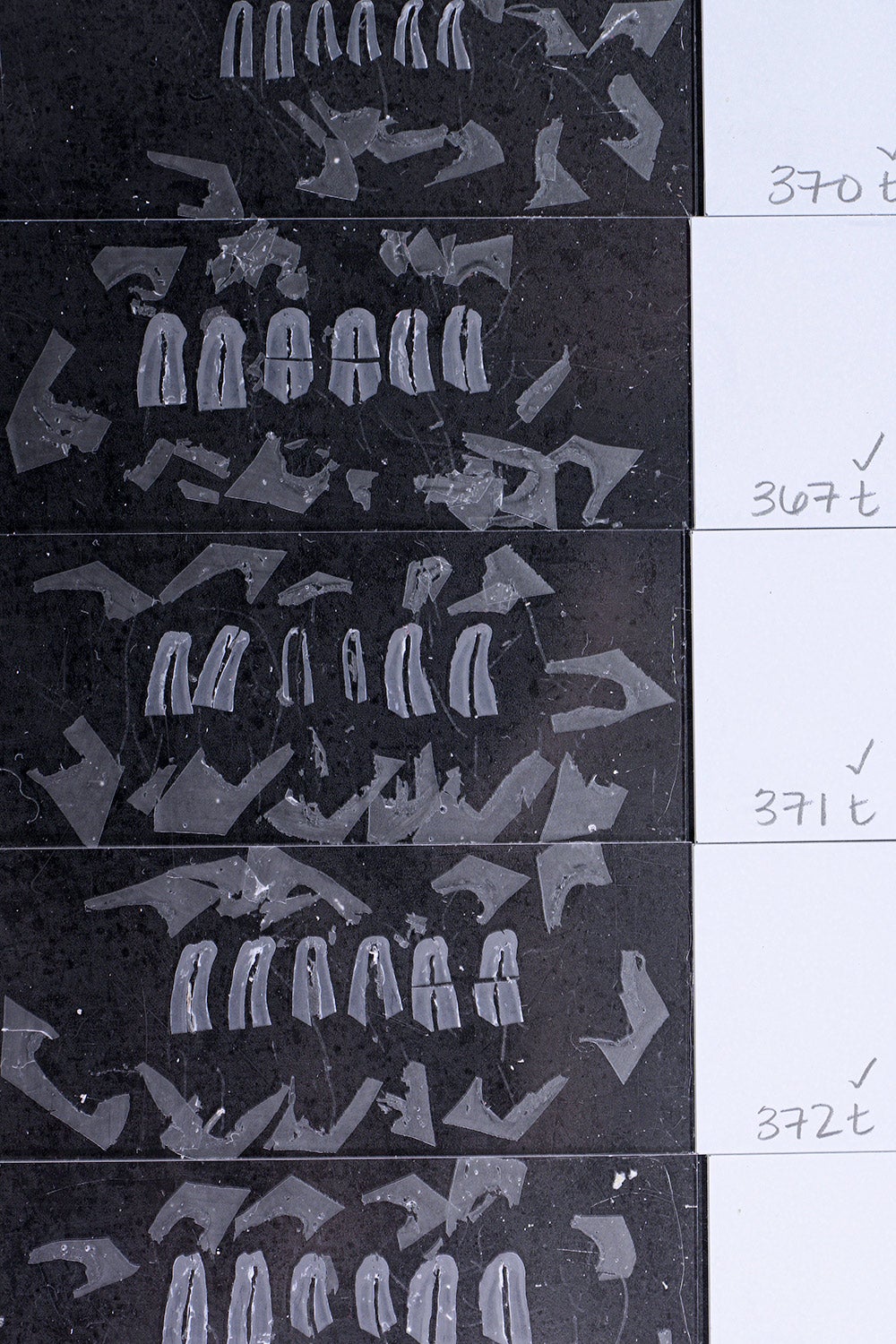

This new client base has become so big that the lab has dedicated a whole storage closet to filing the cross-section slides after they’ve been aged.

“[These are] only from the last five years [of slides], and only the clients who haven’t gotten them back. We probably returned half, or more, of them,” Nistler says, removing a long, thin drawer from a filing cabinet. “We save them for five years in case [hunters] want to refer to something, then we discard them.”

In special cases, teeth get filed in a permanent archival system. The techs at Matson’s have aged teeth for legal cases involving wildlife crimes, says Nistler, and they get the occasional novel species. This might be a big cat from outside the US or a 63-year-old beluga whale. All of these instances warrant keeping the slides.

The Future of Matson’s

Nowadays, Gary and Judy, both well into their 80s, occasionally fly themselves over to Manhattan from Bonner to visit the lab, although they haven’t been in a long time. Gary talks about the lab with detached warmth. It’s in Nistler and Stephens’ hands now, and Gary trusts them to carry the tradition into the future.

“Carolyn has done a much better job of taking advantage of the [hunter] opportunity,” Matson says. “If you’ve ever read [Jim] Posewitz’ Fair Chase, it’s that idea of what hunting is. Part of that ethic is learning as many things as you can about the animal. I appreciate that hunters want to know that information. I think Carolyn has done a better job of making the lab more accessible to hunters that way.”

To Nistler, Stephens, and the rest of the Matson’s team, not only is the work still a viable way to make a living, but it’s also fulfilling. It has to be. Otherwise, the volume and repetition, much like the cementum layers, would start to stack up.

“Lab work is not for everybody,” Nistler says. Some of the steps can become monotonous. But they have to be in order to get through 10,000 to 12,000 samples per month. It’s really important to put what we’re doing into context. When I’m sitting at the microscope aging, and I’m looking at an 8-year-old mule deer, that’s not just a number. That’s an individual to me. I think everyone has to have that kind of commitment to some level. Everyone here is a committed conservationist. They’re not all hunters, but they understand the role that hunting plays in conservation and vice versa.”

Read more OL+ stories.

The post An Inside Look at the Wildlife Lab That Ages 10,000 Animals Every Month appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Articles may contain affiliate links which enable us to share in the revenue of any purchases made.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/conservation/wildlife-tooth-aging-matsons-lab/