America Has Always Had a Love Affair with Its Service Rifles

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

This story, “The American Rifle,” appeared in the August 2007 issue of Outdoor Life.

Since earliest Colonial times, Americans have carried on a love affair with their guns. But it was in 1903 that a singular landmark occurrence made our undying romance with military rifles unique among the nations of the world. That was the birth year, of course, of the 1903 Springfield rifle, and also the year of the first National Rifle Championships. But of far greater impact that year was the creation by the U.S. Congress of the National Board for Promotion of Rifle Practice (NBPRP).*

Supported by President Theodore Roosevelt, himself a keen rifleman, the NBPRP, among other things, authorized further cooperation between the Army and the National Rifle Association (NRA), which had been established back in the 1870s when two former Union officers, Col. William Church and Gen. George Wingate, set out to do something about the atrociously bad marksmanship they had witnessed during the Civil War.

Of significant importance in the NBPRP deal was the distribution of rifles and ammo to civilians for practice and target shooting. This resulted in a cadre of skilled civilian marksmen — the original intent of Church and Wingate — at no cost to the U.S. government other than supplying arms and ammunition, the benefits of which became apparent when we entered the First World War. Not only did good numbers of newly enlisted American soldiers know how to shoot well, but they could teach others. And the ’03 Springfield gave them the best gun on the battlefield.

The NBPRP continued to yield major dividends after the First World War. Thousands of returning doughboys who had fallen in love with the ’03 and wanted to continue shooting it took to the target ranges and “across the course”-type, high-power rifle target shooting blossomed.

Springfield Armory, with not much else to do following the war, supplied target shooters with refined versions of the ’03 offered on loan or for sale to civilians.

Given the almost universal love and respect lavished upon the ’03 Springfield in all of its forms, America’s shooters were probably horrified the day in 1936 when word spread that it was to be discontinued and replaced by — gasp — an autoloader!

The Awesome Garand

Developed by Springfield Armory’s John Garand, the M-1, as it was to be known, could rip off eight shots as fast as the trigger was pulled. This was fine on the battlefield, but target range soothsayers reckoned that such a rifle had no place in the polite company of good bolt-action rifles. Like the ’03 Springfield, it fired the .30 U.S. (.30/06) cartridge, but there the similarity ended. It certainly didn’t have the look and feel of a target rifle, its sights lacked the fine adjustments necessary for bull’s-eye precision and, worse yet, it actually had a hole in the barrel to vent gas for powering its autoloading mechanism.

It was common knowledge that autoloaders simply weren’t accurate. Barn doors, it was predicted, would be safe from assault by the clumsy looking Garand. No way could it compete on the target range with a finely tuned ’03. But these concerns were temporarily put aside when America again went to war, during which the ugly M-1 rifle won praise from no less a military tactician than General Omar Bradley as the “greatest instrument of battle yet devised.”

At the close of WWII, America’s big-bore target shooters, now reinforced by returning GIs and supported by the NBPRP, again took to the target ranges. Old-timers still clung to their beloved ’03s, and commercial rifles, such as target versions of Winchester’s M-70 bolt rifle, gained popularity. But just as veterans of the First World War had an affinity for the ’03, veterans of the Second World War came home with similar affections for the Garand. This affair was made all the sweeter when the NBPRP issued M-ls and ammo to NRA-affiliated clubs and members. Shooters old and young — especially veterans with young families and tight budgets — could spend an almost cost-free weekend banging away at the shooting range. America’s love for its service rifles blossomed as never before.

Carmichel? (He’s the lean-looking kid on the left in the back row.) Photo courtesy Jim Carmichel

Even so, the M-1 and its devotees faced what they perceived to be a daunting challenge. The premier event in rifle competition, known as the Leg Match (where “legs” toward earning the much-desired Distinguished Marksman Award could be won), had to be fired with the service rifle — the inaccurate M-1 Garand!

As it turned out, predictions that the Garand would never be a fit target rifle were way off the mark. Just as accuracy specialists at Springfield Armory a generation before had fine-honed the ’03, the same magic was worked with Garands, resulting in National Match M-ls that rivaled the old ’03s for accuracy and then some. Records that had been set with ’03s years before began falling to a new generation of marksmen armed with Garands.

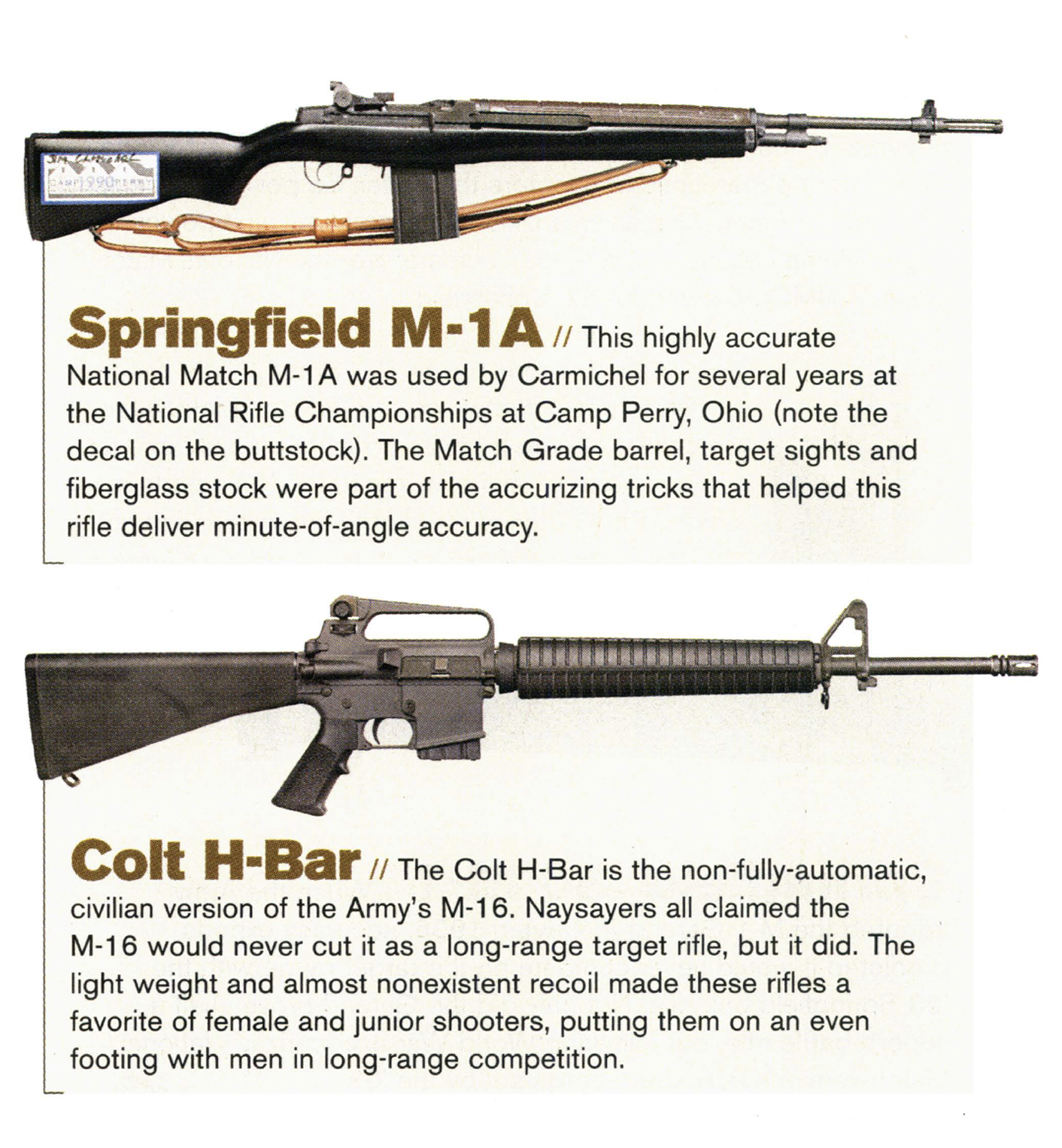

In 1957, after two decades of service that included two major wars, the old warhorse Garand was retired and officially replaced by the M-14. From an accuracy standpoint, getting target-quality performance from the new rifle was almost a no-brainer. What was known about making the Garand more accurate was simply applied to the M-14, the design of which had already eliminated some of the Garand’s idiosyncrasies. This latest service rifle also fired a new round called the 7.62x51mm, known in civilian circles as the .308 Winchester, and soon proved itself superbly accurate, winning Olympic Gold, among other awards. Just as the Garand had eclipsed range records held by the ’03, the M-14 set even higher standards of accuracy and performance. Yet for whatever reasons, the M-14 never captured the affections and loyalties that American shooters have lavished on the old ’03s and Garands.

Today’s ARs

In 1964, the M-14 was phased out and replaced with a truly strange-looking rifle known as the AR-15, or M-16 in military lingo. Not having been developed at Springfield Armory, this newest weapon represented a radical change in Pentagon policy — it wasn’t even of .30 caliber. A new era had begun.

Lighter than the M-14 by a pound and a half, the AR was suited to the forests of Vietnam, where it was first used in battle. Also, its cartridge, the little 5.56x45mm (.223 Remington), could be packed and carried in greater numbers, per weight, than the .30 U.S. calibers of yore.

These and other features seemed to bode well for the autoloading M-16, which was capable of full automatic fire. But reports came from the jungles of Southeast Asia of the rifle’s failure to function at critical times. Also, for better or worse, reports from woefully misguided — or overly imaginative — correspondents told of how the M-16’s tiny but speedy bullets tumbled end over end in flight, like a “buzz saw,” ripping enemy flesh. In time the M-16’s functional problems were solved by design changes and improved maintenance, but the buzz-saw legend, like other goofy rumors, lives on to this day.

As with the Garand of six decades earlier, it was deja vu all over again, with learned declarations of the AR-15 not being suited to the target range. The little 55-grain bullet might be fine for the 200- or even 300-yard stages of the NMC, but at 600 yards it was like tossing chaff to the wind. And at 1,000 yards? Forget about it.

I confess that I, too, succumbed to this line of thinking. In my 1975 book, The Modern Rifle, I stated: “So far the M-16 has met with only mixed success as a target rifle. Despite its Buck Rogers profile, it can be accurately aimed and fired, and the nonexistent recoil makes it pleasant and easy to control in the rapid-fire stages. But the short, 55-grain bullet, despite its nearly 3,200 fps muzzle velocity, can’t get the job done out at the 600-yard target — the rapid loss of velocity beyond 300 yards simply takes the spunk out of the slug.”

Even as these shortsighted thoughts were being set to paper, however, solutions were being found for the M-16’s long-range shortcomings. Downrange accuracy and wind resistance, for example, were vastly improved by such ballistics sleight of hand as combining heavy bullets with fast-twist, target-grade barrels, making some ARs reliable performers even out to 1,000 yards. As these and other improvements proved their worth on the target range, the AR and AR-types came to dominate competition. Women and junior shooters, who had been turned off by the weight and recoil of the earlier .30-caliber service-type rifles, could now compete with men on an even footing.

Today, the ARs not only rule the high-power target ranges but have become the gun industry’s 800-pound gorilla, with more companies making this type of rifle than can be listed here. In an otherwise flat gun business, dozens of manufacturers are kept busy supplying the insatiable demands for barrels, stocks, sights, mounts, magazines and an astonishing assortment of accessories and add-ons for ARs and their endless variety of look-alikes.

Read Next: The M1 Garand, the Greatest Generation’s Service Rifle

In addition to target shooters who dote on their tournament-winning ARs and plinkers who get their kicks slaying tin cans, hunters are taking a closer look at heavier caliber versions, and growing numbers of varmint shooters are discovering that heavy-barreled, scope-sighted ARs rival the accuracy of bolt-action varmint rifles and are great fun for shooting at prairie dogs.

Of course, there are still plenty of traditional-minded hunters and shooters who are turned off by “black rifles,” tending to ignore them in the hopes that they are a passing fad and will eventually go away. But that is like ignoring an onrushing tsunami, because the AR-types, like the ’03 Springfields of a century past, are winning the hearts of American shooters.

*The NBPRP has since been replaced by the Civilian Marksmanship Program.

The post America Has Always Had a Love Affair with Its Service Rifles appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/guns/americas-service-rifles/