I Stalked America’s Most Dangerous Game in the Riskiest Place Possible

This story, “The Bear Chose Me,” appeared in the June 1956 issue of Outdoor Life. Polly Creek lies inside the boundary of what is now Lake Clark National Park & Preserve.

His mouth was half open in surprise, his wet tongue lolling sideways between the huge teeth. I noticed rather incongruously that there was a salmon scale plastered on his big black nose. The bear’s head wasn’t the length of five gun barrels away from us.

“Can’t shoot — too close,” I whispered hoarsely into Max Shellabarger’s good ear.

The guide shrugged. In that single gesture was the whole situation. In this brush you couldn’t possibly see a bear until you were within 30 or 40 feet of him. Even if such a close-range meeting fails to spook the bear, the ease with which he could charge and kill you, even after a mortal wound, is much too obvious to tempt a shot from any prudent hunter.

But I had to admit that Max was right. There were more Alaska brownies at Poly Creek than at any other place I’d ever seen. If you could forget that these big brown bears are perhaps the most dangerous game on the North American continent, then it would be fascinating to meet them nose to nose.

It was Johnnie Swiss who started the whole thing. Johnnie’s an Alaska bush pilot who flies small planes in and out of Anchorage. If there’s a difficult job of landing on a lonely beach or hauling a load of gear into some isolated hunting party, he usually makes the trip.

Johnnie had bought a trapline on Poly Creek, which flows out of the volcanic mountains of the Alaska Peninsula near the mouth of Cook Inlet. Where Poly Creek meets the tidewater there once was a small settlement. Here they canned salmon and also the razor clams which are so abundant on the boulder-strewn beaches during low tides. But the numbers of salmon have dwindled, and the canneries have long since been abandoned. Most of the weather-beaten houses at Poly Creek have been ground into the sedge grass near the beach by the vicious storms that howl down from the Bering Sea.

Just beyond the head of Poly Creek, the original owner of the trapline had erected a tiny cabin on the shores of Crescent River, which lies above Poly Creek like the crossing of a capital T. Both Crescent River and Poly Creek are thick with evergreens. Openings between the trees are filled with alder, willow, and that most repulsive of all Alaska plants, the devil’s-club.

Salmon-hunting brown bears overrun this country. Brownie scares were the major reason why the original trapper had sold out. It’s not healthy to trap where you must walk the bear trails that tunnel the brush along the river.

But Johnnie, who was more interested in piloting bear hunters than in actually trapping his new holdings, was pleased with the bumper crop of bears. “My place is crawling with them,” he told us proudly. “You can take your pick of 40 or 50 big brownies.”

We didn’t have time to go to Kodiak Island or farther out on the Alaska Peninsula where brownies may be hunted gracefully and at a decent distance, so Johnnie’s Poly Creek proposition sounded just right.

“I think you can hop in from the beach and land your plane right at the camp, Max,” Johnnie had said confidently. “That will save us an eight-mile walk.”

Max Shellabarger is also a bush pilot, and I had already been with him as he landed his two-seated Piper on puddles that looked almost too small for frogs. But those harrowing experiences hadn’t prepared me for our arrival at Poly Creek.

We flew in two planes. My brother Joe, a stockbroker from Chicago, went with Johnnie in a wheeled plane which was to land on the beach — if the tide was low enough. There was considerable argument about the tide tables, and if the tide is high, there’s no beach. But this seemed to bother no one but myself. I rode with Max in his float plane. We’d use it to ferry Johnnie and my brother from the beach up to the trapping cabin.

The tide was low, or low enough to reveal a steeply pitched strip of boulder-strewn volcanic sand. It would raise the hair of any ordinary pilot just to fly over it, but Johnnie landed skillfully and wheeled up to an old cabin he’d fixed up to use as a supply house.

If you could forget that these big brown bears are perhaps the most dangerous game on the North American continent, then it would be fascinating to meet them nose to nose.

Max landed our float plane in the very mouth of Poly Creek, where it was no wider than a narrow city lot. Our landing involved slipping down over a rotting wharf of the defunct cannery and then settling in exactly the right place in the creek — so our wings wouldn’t hit the high banks on either side and slow enough to stop short of a tree-trunk snag at the first bend.

We missed all these obstacles by the necessary four or five inches and landed safely. We exchanged passengers then, Johnnie accompanying Max in the float plane to see if they could land up the creek near the cabin. This cautious inspection flight should have warned me, for both Max and Johnnie are hardened dare-devils at landing and taking off in impossible situations. In about an hour the float plane returned and landed in the open water beyond creek mouth. The waves were pretty high, but they seemed a minor hazard under the circumstances. Max peered out and explained that he had left Johnnie up the creek, “to chop out a few snags that seemed to be in the way.”

Noting that Max himself looked a little pale, I got in and braced myself. We had difficulty taking off in the rough waters of Cook Inlet. After we had bounced eight or 10 times and become air-borne, the Poly Creek country began to unfold close beneath us.

Just above the old cannery buildings a large sow brownie with two cubs stood in midstream with the salmon swirling around them.

Just above, another big brownie ambled along the edge of the brush bordering the creek. In a few minutes’ flying time we saw 10 bears, and it was already so late in the day that most of the brownies had finished fishing and curled up in the brush to belch.

Excited at seeing so much game, I forgot about the hazards of flying until we passed the beaver ponds at the head of Poly Creek and crossed the short interval to Crescent River. Then the plane settled beneath us. Max was apparently heading for a riffle on the river with a gravel bar at its far end. The water was white and angry here and apparently dropped 20 feet or so in the short space of the rapids.

The idea was to land the little plane upstream, so that our forward momentum would be cut by the current rushing against us. But neither the neatness of the theory nor the knowledge that Max had already landed on this awful place once before gave me much comfort.

Johnnie was standing in the cold water at the upper end of the riffle, waving his ax above his head to bring us in. And in we came, like a goose stricken with a full charge of No. 2 shot. The floats banged on the white water with just enough momentum left to push us ahead to the gravel bar.

Johnnie grinned as he helped me unload our gear. We both watched with fascination as Max jerked the plane around in the swift current and took off downstream. He was using the rushing water to help gain flying speed in the short run before brush and trees would engulf him. It worked, but with no room to spare.

That short hop from the beach had plunged us into the very middle of the best bear country I had ever seen. The little gravel bar was packed down by their big feet. As Johnnie shouldered a bag of duffel and plunged into the wall of willow on the bank, he followed a trail worn smooth by bears passing this way to fish for salmon in the river. There were half-eaten fish and piles of dung on the trail, and the willows bordering the path were worn by the passage of countless wide-beamed brownies.

The trapping cabin was a story in itself. I had seen Alaska trapping hangouts before, but never one so gloomy and sinister as this one. It was low and squat, with widespread eaves to fend off winter snow. Devil’s-club grew high around the weathered logs. What little light might have filtered through the spiny leaves of the devil’s-club was shut off by towering spruce trees.

Johnnie had sealed the cabin door with an extra iron bar to keep out bears, which had furrowed the wood with long claws. A kerosene can normally used to carry water from the creek was laced with tooth punctures as big across as a man’s thumb. Apparently the brownies were doing all they could to remove this cabin and its human smells from their domain.

We unbarred the splintered door and ducked into the dark interior. There were a few items left by the former owner. Mostly the furniture was that which a man can make unaided with only an ax. Outside of ourselves, no one had ever reached this place without a laborious trek afoot along the bear trails from the beach, carrying whatever he could on his back.

Airing out the musty odor as best we could, we settled ourselves and lighted a fire in the old gasoline can that served as a stove. In a few minutes Max returned with the last load from the beach and again made the perilous landing on the creek. For a man on foot, the trip would take most of the day.

Johnnie explained the lay of the land to us so we could scout the area in the few hours before dark. As he talked, he drew a little map in the mud in front of the cabin, furrowing the dark earth with part of an old beaver trap.

“Crescent River and Poly Creek split up into sloughs,” he said, drawing a series of roughly parallel lines. “These are where the salmon spawn-and where the bears will be.” Then he held up his hand and added, “But be careful. The brownies will be right on you before you see them.”

“Here’s a bush pilot who’s flown through a hundred fantastic escapades,” I told myself, “and he’s advising us to be careful. What are we getting into?”

My brother Joe and Johnnie started upstream for a fish creek that parallels Crescent River. In a dozen strides they had disappeared among the devil’s club. Max and I turned east toward a salmon slough at the head of Poly Creek.

Except for a few trees the trapper had blazed, we’d have lost direction entirely. There were bear trails everywhere, deep-worn avenues leading to and from the better salmon pools. At the slough Johnnie had directed us to, the bear trail we’d been following simply dipped down between dense willows into the water. On the bank in the shadow lay fragments of a dog salmon’s head that looked as if they’d been dropped only minutes before.

We stepped down into water up to our knees. Out in the very middle of the stream we could see up and down for a few yards before the brush protruding from both sides cut off the view. First we tried wading up the middle of the stream, but this was obviously not the answer. Around each of the many dead trees that had fallen into the water, the current had sucked away the gravel bottom to leave green pools. These, as we discovered by trying to get through the first one, were more than waist-deep.

So we waded where we could and then dodged back to follow the bear trails along either bank. These stream-bordering trails had many small loops and side paths down to the pools where the bears could catch unwary fish. All along we found tracks and sign so fresh that it appeared the brownies were just ahead of us.

The dank odor of rotting salmon and bear droppings had been around us constantly. But this new smell suggested wet animal hair. We took one step forward.

Max and I tiptoed along looking this way and that like a couple of burglars. The woods were silent around us. There was only the low murmur of the water as it passed by some hidden snag around the next bend. When a small spruce squirrel chittered suddenly and ran along a fallen log, we both clutched our guns and whirled, then grinned foolishly at each other.

Once, through a rare gap in the trees, we saw Redoubt Volcano, some 20 miles to the north of us. The sun was red on the snow fields of the great mountain, and evening shadows were already gathering in our little valley. It was a tingling business tiptoeing around among brown bears in the daylight; by dark it would be straight suicide.

“Max,” I whispered. “I’ve been farther away from animals in a zoo—”

Max held up his hand. I knew that his hearing had been dulled somewhat by several awful experiences in subzero weather and the roar of airplane engines, but he uses a hearing aid that was now tuned to pick up sounds too dim for normal ears. I could hear nothing. Still, there did seem to be something. Was that the smell of a bear?

The dank odor of rotting salmon and bear droppings had been around us constantly. But this new smell suggested wet animal hair. We could see nothing in the shadows either ahead or behind us. A salmon splashed in the creek just beyond the willows. That was all. We took one step forward.

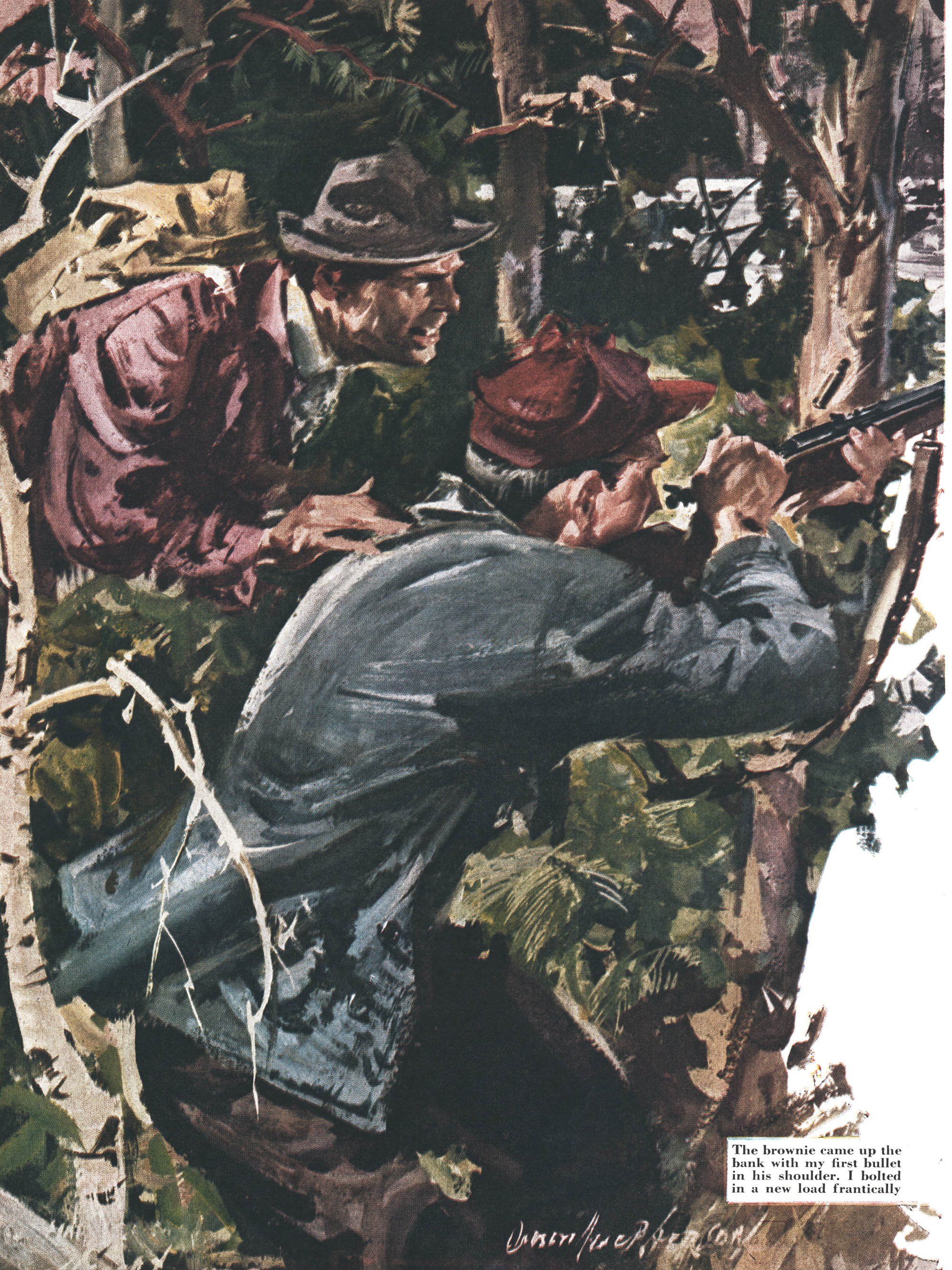

With a rush the brownie rose before us on the other side of a bush, his head looming up big as a bushel basket and almost black in the shadows. Both Max and I started back a step and thrust our rifles forward.

Now I could see the bear’s bright little eyes on either side of his long, straight muzzle. His whole attitude was one of surprise. And so was mine. I could have spit in his eye, if that was the right thing to do. Just what should I do with a great brownie so close I might bat his black nose with a tennis racket?

Max and I stood there with our mouths open like two gasping fish. I suppose I’d have fired if the bear had lunged forward through the bush, but I must admit that for those few seconds I forgot I was supposed to be hunting bear. Then the bruin dropped down on all fours and ran. We saw the bushes waving as his great body passed through. Spurts of spray flew above the willows as he crossed the creek. Then all was quiet again.

That evening, back at the little trapping cabin, we compared notes. Joe and Johnnie had seen six bears, all within arm’s reach. Three of them were yearlings which they said they didn’t want to shoot. They gave no reason for refusing all the others, but Max and I knew why.

We ourselves had seen four bears that same evening, all of which ran from us. How long would it be before we met one that elected to run at us?

Suddenly, across the creek, the brush swished violently and a big round head broke through the leaves.

I pondered this question as we sat there in the little cabin and talked by the glow of the fire through the cracks of the makeshift stove. And later that night, as I tossed and turned on a narrow bunk made of rope laced over a log frame, it wasn’t the rough bed or the smell of old beaver pelts which kept me awake. I even imagined during the night that I heard a bear pass close to the cabin. There was a loud snuffling out there in the darkness and something kicked one of the tin cans in front of the door.

In the morning Max and I decided to cross over the bear trails to the head of Poly Creek. From the plane we’d seen several grown-over beaver dams at the very head of the creek. These small openings just might give us a chance to see a shootable bear far enough away to shoot him. Johnnie and Joe, after some deliberation, decided to try the sloughs off Crescent River again, especially to find one yellow-furred bear they’d glimpsed the previous evening.

By following old blaze marks, Max and I found our way to Poly Creek. After that it was like navigating in a fog, for there were brush-screened sloughs, side creeks, and beaver dams in Max Shellabarger with author’s brownie profusion. The morning was still as death, except for the gulls twittering above the ripples of the creek as they fed on drifting salmon eggs. Two bald eagles swooped low over the water and the gulls scattered screaming. Then there was only silence again: Just before us, in the mud of the trail, Max pointed to an imprint a good 18 inches long. That would be a brownie of record size in anybody’s book. A small trickle of muddy water was running back into the impressions of the great toes.

Just beyond, a bear had been feeding on the cow parsnips that grew close to the water. We had noticed before that the brownies seemed to enjoy varying their fish diet with a little salad. Suddenly, across the creek, the brush swished violently and a big round head broke through the leaves. Before we could point our rifles in that direction, the head disappeared and crashing brush just across the stream showed the course of the bear as he ran.

Judging by the one glimpse, this brownie was of no great size, but we had no chance to shoot, even if we’d wanted to take him.

Max and I sneaked on like a couple of scouts in Apache territory. We walked in the water when we could, and on streamside bear trails when we couldn’t. We carefully parted the devil’s-club and willow to avoid telltale rasping sounds against our clothes. Yet twice more in the next hour bears lunged away just ahead of us. One of these was an enormous brute, perhaps the maker of that big track we had seen. But there was no time to shoot or even think of shooting before he too was gone.

Eventually Max took off his pack, leaned his rifle against a tree, and began to climb an old birch which leaned out over the creek. About 20 feet up he stopped, pointed excitedly, and started down.

“There’s a big bear fishing around the next bend,” Max said in a hoarse whisper.

For a fleeting moment I thought this was our chance. Then, as we advanced to a solid wall of willow stems, I realized that a stalk was impossible. What if there was a bear catching salmon in the next bend? We wouldn’t spot him until we could actually punch his belly with the rifle barrel. Such a maneuver seemed inadvisable with a brown bear.

Nevertheless, we eased ahead to do our best. We stepped on grass clumps when we could, so our boots wouldn’t make a sucking sound in the mud. The devil’s-club we pushed aside so that it closed silently behind us. At no place could we see more than 15 feet through the awful brush.

Just once, through a rift in the willows, I saw the water of the creek on our left. Here a bear had caught a fish and sprawled at full length in the willows to eat it. The bear’s heavy body had smashed down the growth to form the gap I looked through.

Just ahead we heard the splash of water. A dozen salmon darted by as dark shadows in the current. Something had scared them. Next there was a mighty splash that threw water above the willows. The bear was chasing salmon just around a sharp bend of the little creek.

Max urged me forward with a motion of his hand. I shook my head. There was no use shoving through that willow. It would be the same story all over again.

Again spray spurted above the brush in time with another mighty splash. A dog salmon darted upstream into the pool beside us. A male salmon already there turned savagely to meet the intruder. They locked their hooked jaws and wrestled in the water. The female turned on her side to eject more eggs, apparently not caring which male won. The bear seemed to be working his way upstream.

By bending a couple of willow branches silently out of the way, I made a small opening above the pool where the two dog salmon still fought viciously for the spawning hole. Then I stepped back as far as I could and threw off the safety of my .300 Weatherby Magnum. As· soon as the bear entered that opening, I’d nail him.

Max and I waited there, crouched and ready. The bear’s splashing stopped. One dog salmon broke off the upper jaw of his opponent. The beaten male swirled off weakly in the current and disappeared. The brownie never showed. Apparently he’d caught a fish and carried it ashore to eat it. I finally walked forward a step or two to try to see farther downstream. It was then that the bear came charging up the brush-bordered shallows. I didn’t want to shoot a female or a small male. But now I couldn’t pick and choose. The bear chose me.

This brownie looked as big as a mountain, but I had been tensed so long that I raised the rifle and fired before the question of size entered in. I had meant also to aim carefully and a void shooting high — which is so easy to do at close range — but I fired the instant my sights swung onto his shoulder. Then I was snatching for the bolt to thrust in a new shell.

The brownie came on with my bullet in his shoulder. I fired again at the wide chest, dimly conscious of huge paws reaching over the top of the low bank just in front of me.

With his eyes fixed on us, the bear surged upward almost in reach. But as I frantically bolted in another shell his body began to sink as he gathered his hind feet beneath him for the lunge that would reach me, I aimed where muscles of the neck joined the shoulder. Max laid a restraining hand on my back and said “Let him come.”

There was no time to understand what Max meant. The great round head dropped lower. The bear’s forefeet clawed into the mud of the bank. Still he slipped backward. The head fell on one forepaw and he was still.

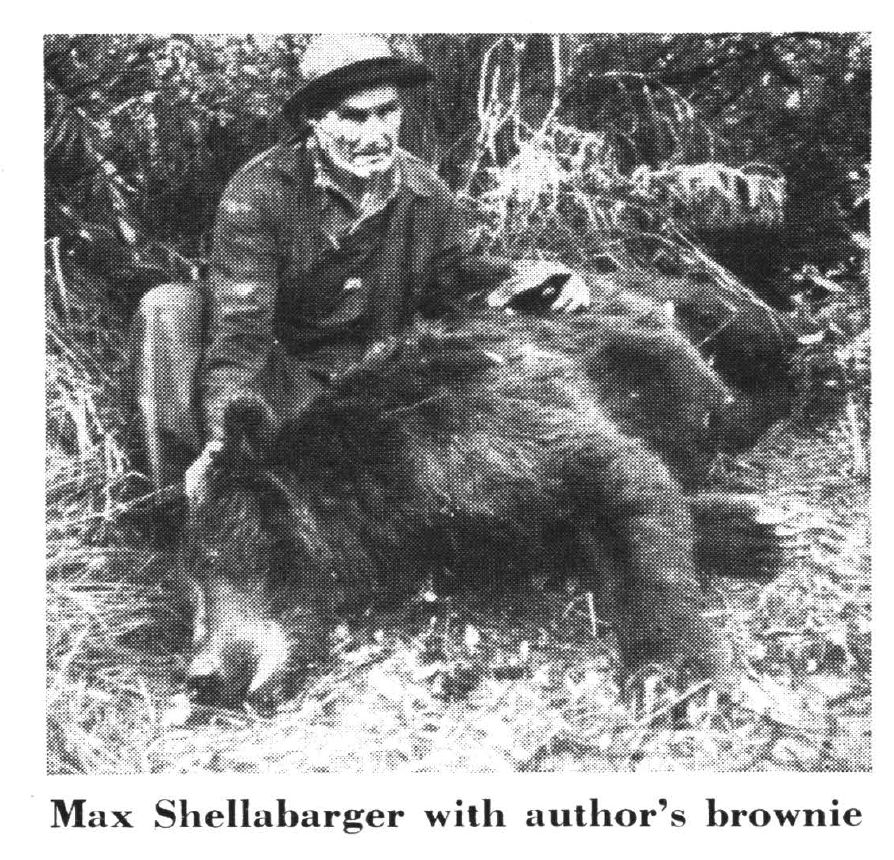

“Should have let him get up on the bank here,” Max said quietly. “We’ll never be able to skin him in the water.”

We did manage to roll the brownie the rest of the way on the bank. While we skinned him there another bear came to look at us, standing up in the brush just across the creek. We saw more bears as we walked back to the cabin, but we were talking loudly and slapping each other on the back so that we scared them away before we got too close.

Back at the cabin Joe and Johnnie were just bringing in the skin of the yellow bear. They excitedly told a story similar to our own. They had found the yellow bear in a tiny clearing at river’s edge. Joe, backed by Johnnie Swiss, had poured seven shots into his bear. After the first shot, the bear had been coming for them.

We packed the skins out to the riffle where the airplane waited. The hazards of a take-off from this fearful place seemed minor after the brushes with brownies. Joe and one bear skin made a load for the first trip to the beach.

Read Next: Who Killed the Side-by-Side Shotgun?

As Johnnie and I turned the plane in swift water and held it while Max speeded up the engine, a large brownie with two cubs splashed across the stream just below us. If we had let the quivering plane go a moment before, Max would have hit the bears with his floats.

“You know,” Johnnie mused, as though the idea had just occurred to him, “a man could get killed hunting bears in this country.”

The post I Stalked America’s Most Dangerous Game in the Riskiest Place Possible appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/brown-bear-hunting-alaska-salmon/