I Was Charged by a Cape Buffalo While Testing One of the Earliest .458 Win. Mags

This story, “A Bad Cup of Tea,” appeared in the April 1957 issue of Outdoor Life.

We were after elephants and our hunting camp was set up on a bend of the Tana River, in the Bura district of Kenya some 300 miles northeast of Nairobi.

For three or four days Louis Woodruff, my outfitter and white hunter, held me to antelope of one kind and another, and I knew he was feeling me out, sizing up my shooting before he let me play in the majors. That was all right with me, too. I ordinarily shoot a high-powered rifle about once a year and make no claim to being an expert. I was as glad for an opportunity to test my shooting as Woodruff was.

I collected a gerenuk and a lesser kudu with horns just under 32 inches, one of the best minor trophies I took on the whole safari. Both were clean kills with the .270 bolt-action Remington I had shipped to Africa for my hunt.

Then I started having trouble anchoring game with that rifle. It put ’em down but they didn’t stay. I wounded a fringe-eared oryx, followed the blood trail until dark, and lost my trophy to the hyenas during the night. I made it up the next day, picking off a beauty, but it took two shots to turn the trick. When I had the same experience with a zebra stallion, a topi, and a waterbuck I put the .270 away and fell back on a .375 Magnum Model 70 Winchester. From then on I had no more trouble. The larger .375 put them down for keeps.

The .270 is a great rifle for the work it’s meant to do, especially in expert hands. But some African antelope are bigger than you expect (the eland is about the size of a small horse) and they seem to take more killing than deer and other soft-skinned game in this country.

Woodruff finally announced I was ready for bigger business. We ate breakfast at first light and he and I piled into the battered lorry that carried our camp gear, with three trackers, a couple of gunbearers, a skinner, and two or three other safari boys. We headed for the Somaliland border, 80 or 90 miles east of the Tana. “There’s a bit of elephant country over there I want to have a look at,” Woody explained.

I elected to ride on top of the truck, where I could see the country and keep watch for game, and we hadn’t driven many miles when I spotted a rhino off to the left of the road. He looked about the size of a small barn.

I yelled to the driver to stop, and Woody and I climbed down. The commotion sent the rhino lumbering off, but he ran only about 400 yards before he wheeled around and stood eyeing the lorry with a grumpy stare, as if uncertain whether to clear out or come back and clobber whatever had disturbed him.

Woodruff and the tracker led me off on a wide circle, so we could work upwind and approach him from the rear. He was standing in thick, low bush, still glaring at the truck. But we were in the open, and when Woody kept going until we were only 25 paces away I began to get uneasy. Then the rhino heard us. He swiveled around and came, and I felt as if I were standing in the center of a railroad track with a locomotive bearing down.

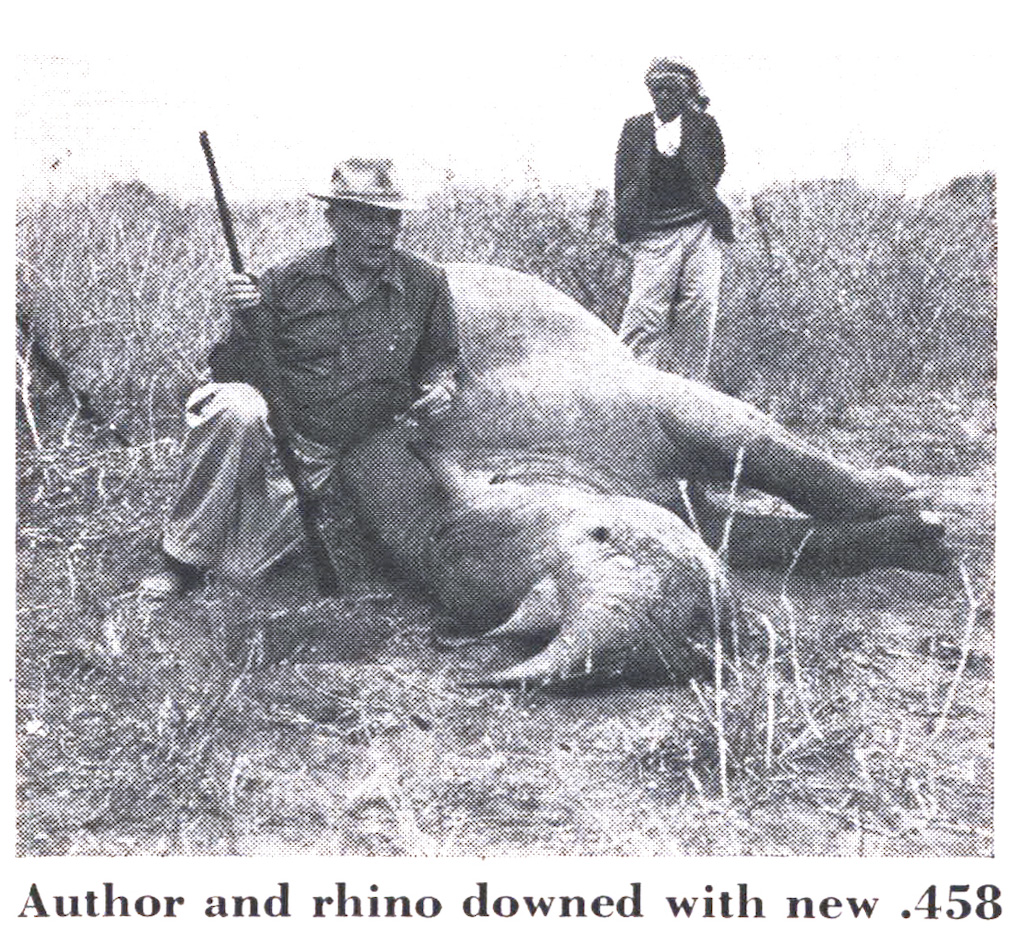

In addition to the .270 and .375 rifles I’d shipped to Africa, Winchester had sent along another Model 70 in .458 caliber. It was the company’s new elephant gun. They wanted my hunting partner, Dick Heck, and me to test it on Africa’s big game. This was in August of 1955, months before the .458 was announced for general sale.

Related: The 10 Best Dangerous Game Cartridges

I was carrying the new .458 that morning. It had a peep rear sight and I soon had reason to believe that’s an error on any gun intended for dangerous game.

I brought the rifle up with the rhino pounding down on us, and I simply couldn’t locate a vital target area through that sight. When he was 15 yards off I didn’t dare wait any longer. I just slammed a bullet into him, hoping it would hit where it would do the most good.

The .458 moves a 500-grain solid bullet at the lively clip of 2,125 feet per second, and packs a muzzle wallop of more than 5,000 foot pounds. But that wasn’t enough to turn Mr. Horns, not where I hit him. It took a second solid, from Woodruff’s .475 double rifle, to do that. When I heard its heavy blast, with the rhino still heading in on us, I knew we were in a very tight spot, for Woody won’t butt in unless it’s absolutely necessary.

His shot slewed the black hulk halfway around. By that time I’d bolted in a fresh hull and I fired again. That turned him some more, and as he lumbered away I smacked him in the rump, trying for the base of the spine. That one did it. He piled up in a heap, gored the ground a few times with his horn, and turned into a good rhino.

He should have. He’d absorbed 2,000 grains of high-speed poison. My first shot had caught him between the eyes, not a lethal spot with his breed. Woodruff’s was a haymaker in the shoulder. My second shot had opened up a big hole in his lungs, and my last one demolished his rear axle.

I had heard and read many times before I went on the hunt that a rhino is the most slow-witted of Africa’s big five, which includes the elephant, buffalo, lion, and leopard. That may be so, but you don’t stop a rhino making a determined charge by outwitting him. You have to shoot him. My rhino was my first major trophy of the safari, and no matter how long I live I’ll never forget the way he looked when he came pounding at us, head down and tail up, as square and bulky as a tank.

I had left my home in Pineville, Kentucky, on August 5. I did a bit of sightseeing on the way, and stepped down from my plane at Nairobi six days later. My hunting partner Dick Heck, who operates some tobacco warehouses in Madison, Indiana, had arrived in Africa two weeks before, and he was off in the Masai country hunting lions with Mohamed Bal, a Pakistani professional hunter employed by Woodruff. Bali, to use the nickname given Mohamed Bal by his friends in East Africa, is a driver of racing cars (an accomplishment which came in handy before the hunt was over); a fine hunter, and a generally competent hand on safari.

The plan was for Woodruff and me to join Bali and Dick near Salengai. But the afternoon I landed at Nairobi Heck knocked over a fine black-maned lion, and that wound up his Masai-country hunt. He and Bali sent a runner out to the nearest town and got off a telegram to Woodruff to let him know about the lion.

That evening on Safari News, a special broadcast put out each night by a local radio station to all hunting parties out of Nairobi, Woody sent instructions to Bali and Heck to come back to Nairobi. They hurried, knowing we had elephants up our sleeve, and arrived the next noon.

We loaded the lorry and a four-wheel-drive hunting car — which is called a shooting brake in East Africa — and drove out of Nairobi on the morning of August 13 with a dozen safari boys. We headed up through the Mau Mau country to the Northern Frontier District and the Tana. When we checked in with the district commissioner at Garissa we were told that elephants were doing mischief around Bura, so we moved there and established camp. Woody and Bali let it be known among the local natives that we’d pay suitable rewards for word of elephants with good ivory. Then we started hunting antelope-sharpening our marksmanship for the dangerous game to come, as I related earlier.

We followed the blood sign, ready for trouble, and hadn’t gone far before we found it. I heard a warning shout and then a crashing in a thicket ahead.

After that came our rhino fracas, and that same day I got a beautiful male ostrich, which was running full tilt, at close to 200 yards. One shot from the .270 did it, again proving the rifle very much O.K. for the game it’s intended to handle.

Late that afternoon, driving through semi-desert country where flocks of guinea fowl kept getting up at the side of the rutted sand road, we topped a low rise and saw a big water hole ahead. It was about twice the size of a football field, and off to one side of it a herd of 40 to 50 elephants was working slowly through bush and scrub thorn trees.

Woodruff spoke an order in Swahili. Our native driver stopped the lorry and backed up very quietly until we were out of sight of the herd. Then we turned around, still without any commotion, and drove back a couple of miles to make camp.

We headed for the water hole on foot of the herd. The stalk was easy. We made a circle and came in on him upwind, maneuvering so as not to spook any of the others. When Woody finally halted us we were only 50 yards from the bull. I thought it would be easy.

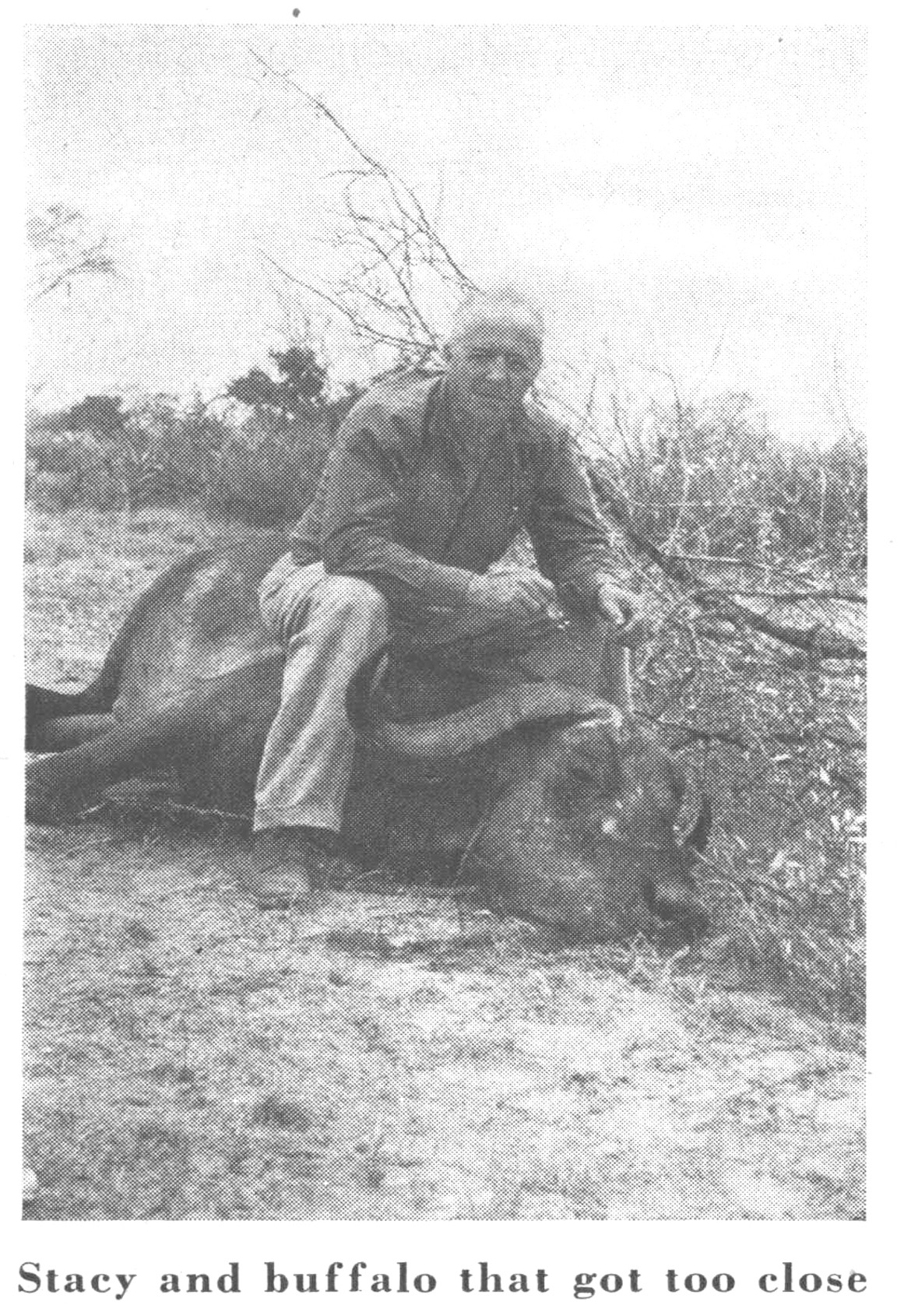

I was carrying the .375, loaded with 300-grain expanding bullets. I laced one into his shoulder that belted him flat as a hoecake, and Woodruff let out an exuberant yell. But our elation died as the bull bounced to his feet. He was out of sight in the bush before I could work my bolt. A wounded buffalo’s a disagreeable customer, and we had one on our hands.

We followed the blood sign, ready for trouble, and hadn’t gone far before we found it. I heard a warning shout from Woody and then a crashing in a thicket ahead. Next I caught glimpses of three buffaloes coming at a dead run, one close enough to call for instant attention.

I drove a shot through the brush and Heck cut loose with the .458. The buff careened around the thicket, 25 paces away, heading in on us, and I saw that it was not my wounded bull. This one was smaller, with a poor head, but I had no time to think of that. It turned out later she was a big cow. I had clear shooting now for the first time and I clouted her in the shoulder. She stumbled but stayed on her feet. At 15 yards she stopped with her front legs braced wide apart as if to keep from falling. She shook her head, spraying blood. Then I punched a third shot through her heart and she fell dead.

Things were too hot for the wounded bull by this time. He spooked out of a thicket up ahead, with a second cow trailing him, and was out of sight before we could get a shot. The bright, frothy blood trail indicated a lung shot, but he could still travel and I’ve never been more keyed up than I was for the next half a mile.

When things came to a head a lot happened at once, the way it’s likely to in Africa. A tracker stopped and pointed, with a low grunt in Swahili. There was a knot of eight or 10 buffaloes off to our right, standing motionless and staring back in the direction where we’d done our shooting. Then we saw the wounded bull by himself, about 40 yards away, between us and the herd. He was watching us, and I knew by the way he looked that unless we killed him somebody was going to get hurt.

“Take him!” Woodruff barked.

I saw dust fly from his black hide at my shot but he didn’t even flinch. A second later he was coming for us full throttle. Bedlam broke loose. The four trackers scattered for the brush, running like streaks. Woody’s .475 bellowed but it had no effect. Heck rapped out a shot with the .458 and then ran past me around a thorn thicket, looking for a clear spot from which to make his next try. In the confusion I lost track of Woodruff.

The bull was still bearing down, and so far as I could tell right then I had things all to myself — and I knew there were eight or 10 more buffs that we might hear from at any second.

My bull rounded a thicket 15 yards off, coming for the wind-up, still a long way from a candidate for taxidermy. I’d only get one more chance now.

I drilled my soft-point bullet into him just over an eye. It was a lucky shot, for the place where you can hit a buffalo in the head and do good is pretty small. It smashed through and opened up in his brain, 300 grains of instant death. He conked out as if lightning had hit him, but the momentum of his charge carried him on. When he slid to a stop I took eight steps and touched him with my toe. That’s too close.

He conked out as if lightning had hit him, but the momentum of his charge carried him on. When he slid to a stop I took eight steps and touched him with my toe

When I turned around Woody was standing just behind me, as I might have known he’d be, with his .475 lifted to put in the finisher at the last second if I failed. But I’m glad he gave me my chance and glad I didn’t know he was there until it was all over, for nothing else that ever happened to me on a hunt gave me the thrills that scrape did.

“Bloody good show,” Woodruff said quietly, and just then we heard a commotion off to the right. The eight or 10 buffs that had watched the whole thing had finally decided to clear out. They thundered off, with a blackish calf wobbling along in the rear.

That should have been the end of the story. But we still had a few bad hours ahead.

We had in our crew an aged tracker, Kubresh, who had served Teddy Roosevelt as a gunbearer back around 1909. Woodruff now put the skinners to work on the bull and the big cow we’d killed, and started Kubresh back to camp with instructions to Bali to come for us with the hunting car. The skinners found, among other things, that we had blown the bull’s heart to a pulp. Yet he was still coming strong when my last shot, in the brain, finally belted him down.

We waited hours for Bali and at last sent another tracker to fetch him. He arrived promptly that time, bringing word that Kubresh hadn’t reached camp. We spent the rest of the afternoon searching for the old native and gave up at dark, sure some mishap had overtaken him. The boys sang in my honor around the fire that night, celebrating my buffalo kill, but I was in no mood to enjoy it. Off on the plains the hyenas were howling, and I could picture a hellish pack of them surrounding poor old Kubresh.

We looked for him again at daybreak. The trackers picked up his tracks now and stayed with them, and an hour past noon we found the old man, wandering aimlessly — but safe. He said a buffalo had chased him the day before, but Woodruff and Bali didn’t believe his story. “Lost,” Woody grumbled. “He’s getting too old for this business.”

Read Next: Carmichel in Australia: Charged by a Backwater Buffalo

We went back to camp and our head boy brought a pitcher of cold limeade to wash the dust of that hot, dry walk out of our throats. So we sat around hashing over the hazards of the hunt.

“Well, any time you come out all right hunting buff aloes you can call it a good do,” Woody summed up with a grin. “They’re a bad cup of tea.”

Remembering how the heart-shot bull had kept coming, and how he looked rounding a thorn clump at 15 yards, I didn’t feel disposed to argue.

The post I Was Charged by a Cape Buffalo While Testing One of the Earliest .458 Win. Mags appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/kenya-cape-buffalo-safari/