Why Most Guns Don’t Blow Up

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

This column by OL’s former shooting editor appeared in the February 1986 issue of Outdoor Life. As current shooting editor John B. Snow points out, not much has changed when it comes to proofing barrels. The purchase of a new gun (particularly a pistol) often used to include an envelope containing an empty casing — supposedly the spent brass from the proof round. Although American companies still proof all their barrels, Snow can’t remember seeing a case like that in years.”American shooters still don’t care about proof marks,” he says. “In fact, we probably care even less because the quality of modern manufacturing is so good.”

Snuggling down behind a fire-blackened stump on the high side of a bitteroot deadfall, you float the crosshairs of your scope across a gang of elk that emerges, ever so cautiously, from the forest’s gloom. A cow comes, then another cow, then a spike bull. Will there be a big bull? Can you hit him at this range? Can you gut him and make it back to camp before dark?

These and dozens of other questions parade through your head like ponies on a carrousel. If you are using a modern, well-made rifle in good condition and the correct ammunition, you don’t bother to ask what will happen when you pull the trigger and 50,000 pounds or so of hell-hot gas erupts only inches from your face. You don’t have to worry about it because there is a tiny, almost unnoticeable mark on most rifles that tells you it is going to withstand the tremendous gas pressures. Possibly, you’ve never paid much attention to that shy little mark, and if you’re like most shooters, you have only a vague understanding of what it means. It’s called the proof mark, and its story is an interesting one indeed, rich in history, tradition, political intrigue, and more than a little scandal.

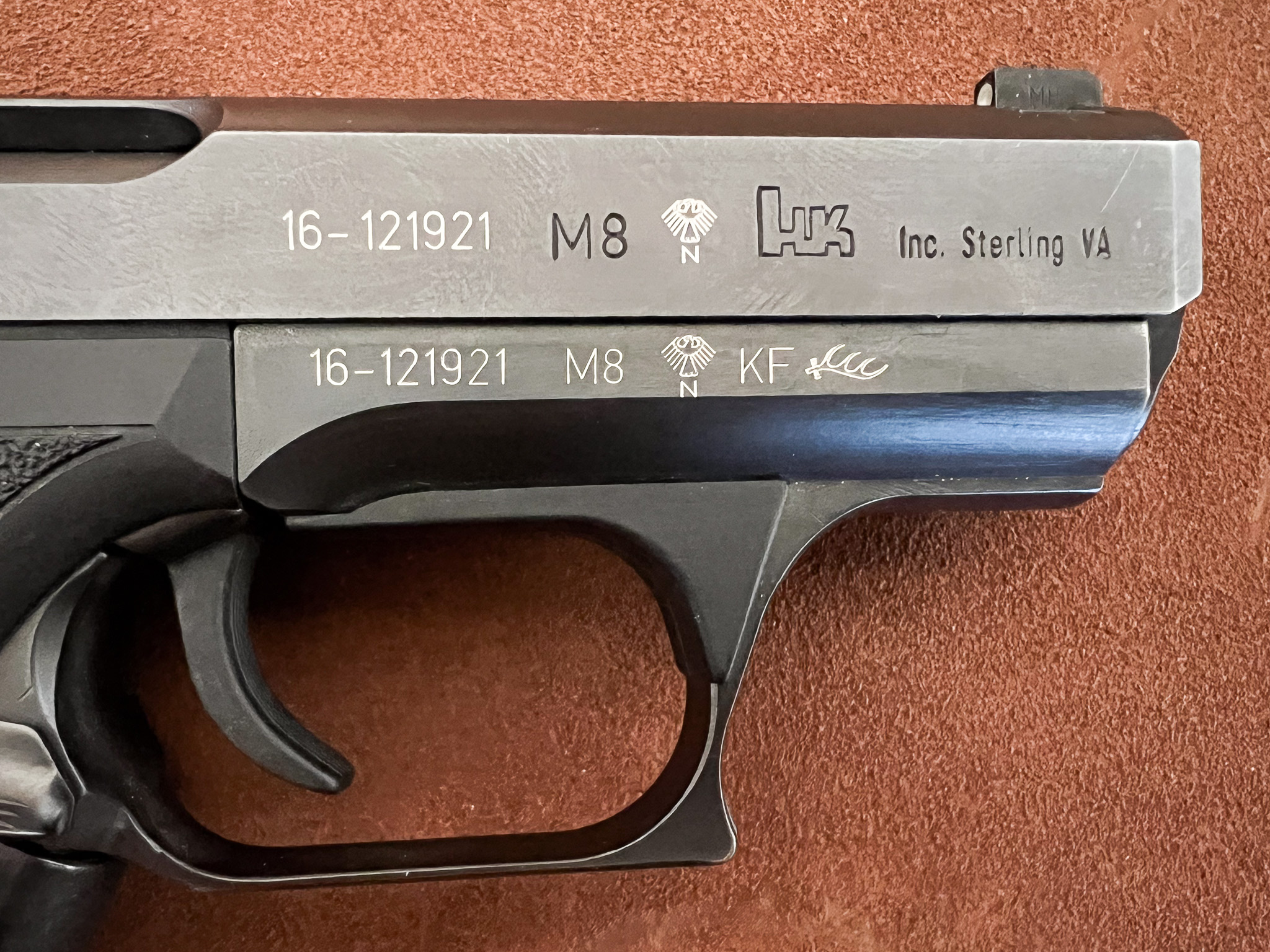

Proof marks come in hundreds of shapes and designs, each one telling something about the gun. Essentially, though, a proof mark means that the strength of the gun has been tested by firing an overloaded cartridge. If the gun digests this overdose of powder, which usually generates one-third to one-half more pressure than a normal load, it can be reasonably assumed that it will safely contain the pressure generated by standard ammunition. If there is no visible or substantially measurable change in the gun after proof firing, the proofmaster applies his sign of approval in the form of an indented seal. Usually, the proof mark is stamped on the barrel, but it may also appear on the receiver and even the stock as well.

Here in the United States, we don’t give much thought to proof marks or to the implications of firearm strength. We just naturally assume that modern American guns are stout enough to withstand the pressure loads to which they are subjected and have a margin of extra strength. In other countries, however, especially Great Britain, shooters are obsessed with the strength of their firearms and constantly inquire about the validity of a gun’s proof. A leading British firearms writer tells me that he receives more letters inquiring about proof than any other shooting matter. Among the thousands of firearms questions I’ve received at Outdoor Life, I can’t recall more than one or two asking about proof or proof marks.

A few years ago, as I was prowling through the musty storerooms of British arms museums, I happened across a former ordnance officer who had been in charge of proof testing the rifles voluntarily donated to Great Britain by Americans during the early World War II emergency. These were good-quality sporting rifles — Springfields, Model 70 Winchesters, and the like — and it had always struck me as more than a little odd that the British would take the time to proof these rifles when they expected the Huns on their beaches at any moment. When I put my question to the man, he puffed and sputtered as though he couldn’t comprehend how I could ask so stupid a question. “My dear fellow,” he finally managed, “the rifles had to be proofed so we could issue them to our home guard.” From this I gathered that the home guard would rather have been bayoneted in their beds than go into battle with weapons that hadn’t been blessed with a British proof mark.

Origins Of Proof

The history of proofing goes back to the earliest days of gun building. Given the metallurgical resources available to early gunsmiths, it was not at all uncommon for a gun barrel to explode, even when charged with a normal load of powder. This was also a major hazard to cannoneers. A confident gunmaker, therefore, would demonstrate the strength and safety of his product by touching it off with an overload of powder. If the firearm held together, the customer was happy, and if it didn’t, the· reputation of the gunsmith was stained.

In time, as middle European gunmakers formed guilds, proofing was done by the guild itself, thus establishing a quasi-official seal of approval for barrels that passed the guild’s test. Those that passed were stamped with the guild’s hallmark.

We can speculate that the severity of proof testing varied from one guild to another, and given the political nature of any such organization, we can also assume that the proof tests were not administered equally to all firearms. Also, if a gunsmith didn’t want to submit his products to proof testing, there was no law that said he had to do so. I expect that during this era it was not exactly unheard of for an unscrupulous gunmaker to stamp his untested barrels with a bogus hallmark.

Keep in mind that during the first centuries of gun building, the making of a barrel was a time consuming process, requiring the finest and most expensive iron and steel available. If a gunsmith could get away with using cheap metal, his profits increased accordingly. This is not to say that gunsmiths tended to have larceny in their souls; almost all gunmakers staked their reputations on the strength of their guns. If a barrel blew up and maimed or killed a customer, the gun’s maker was publicly disgraced and roundly condemned.

From the 14th until the beginning of the 19th century, the matter of proof testing was mainly self-imposed by the gunmakers themselves, either through gun making, blacksmithing, or armorers’ guilds or through a municipal proof house supported by the city’s firearms industry. In some cities, proof was a very serious affair, with the gunmakers themselves demanding rigorous proof standards. By doing so, they were able to demand premium prices.

Naturally, it was only a matter of time until the administration of proof testing passed from the private sector into the everopen hands of local and national governments. When government bureaucrats acquired control over proof testing, the enactment of proof laws and building of government proof houses occurred in very short order. The British Gun Proof Act of 1855, for example, required that every firearm sold in Great Britain be proofed in one of the designated proof houses. Even earlier, in 1810, Napoleon Bonaparte himself required that all French guns pass proof.

An interesting historical note is that government arsenals had required rigid proofing of muskets long before mandatory proofing was required for commercial firearms. Because the European enlisted man was regarded as a rough clod at best, and his superiors showed scarce concern for his general well-being, one has to wonder about the official need to equip him with a well-proofed musket. I suspect this policy was made necessary because many recruits had well-founded fears that their muskets would blow up in their faces. If muskets blew up too frequently and word got out to the public, recruitment would’ become increasingly difficult.

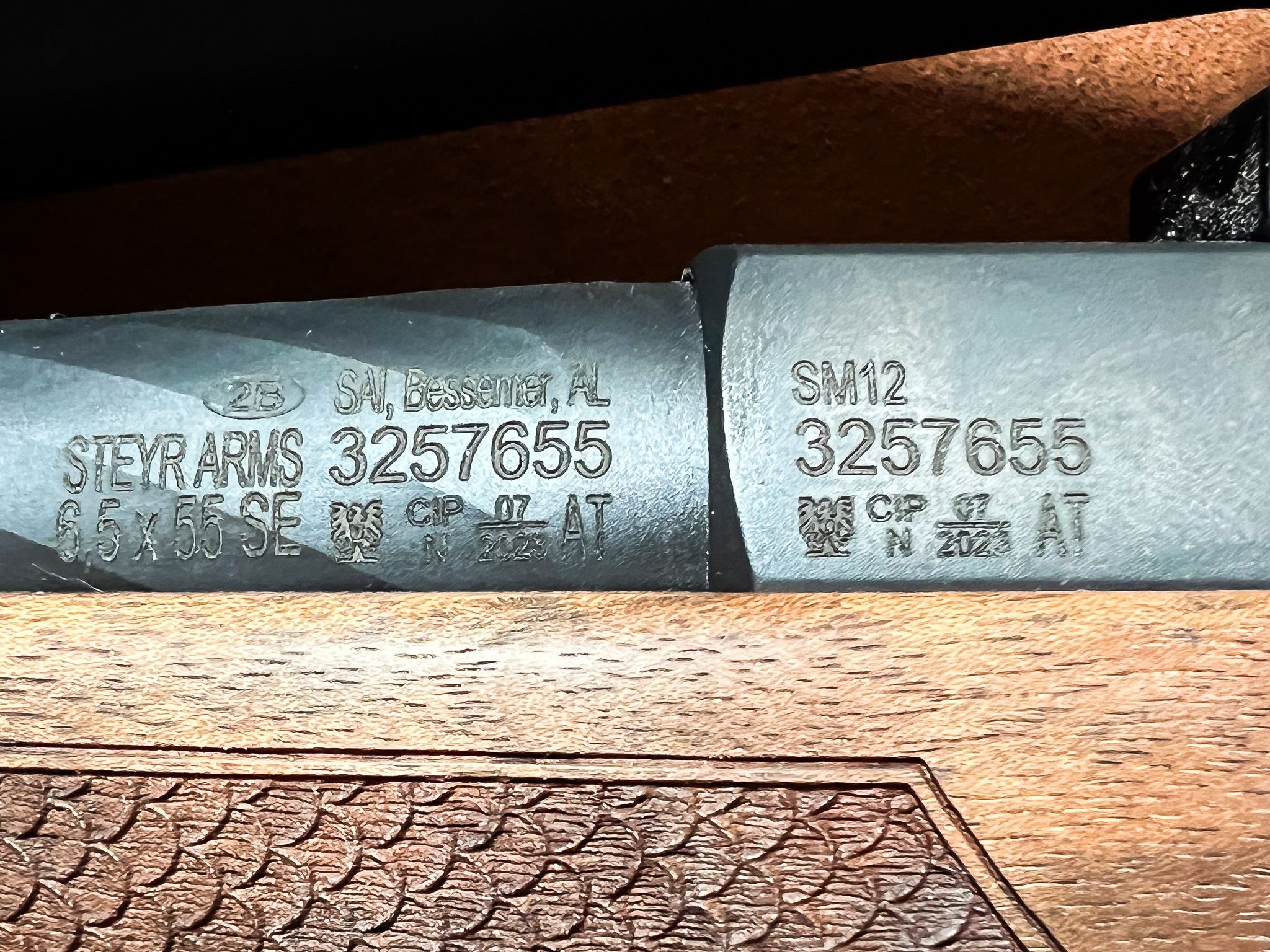

The proof marks stamped on commercial and military arms were quite distinctive and tell modern historians a good deal about a gun’s past, including where it was made and approximately when. The great gun-making cities of Europe, such as London and Birmingham in England, Paris and St. Etienne in France, Liege in Belgium, and Hanover and Munich in Germany, had distinctive, crest-like proof marks that clearly indicated the gun’s origin. And because the proof marks were changed from time to time, it is also relatively easy to establish the approximate date.

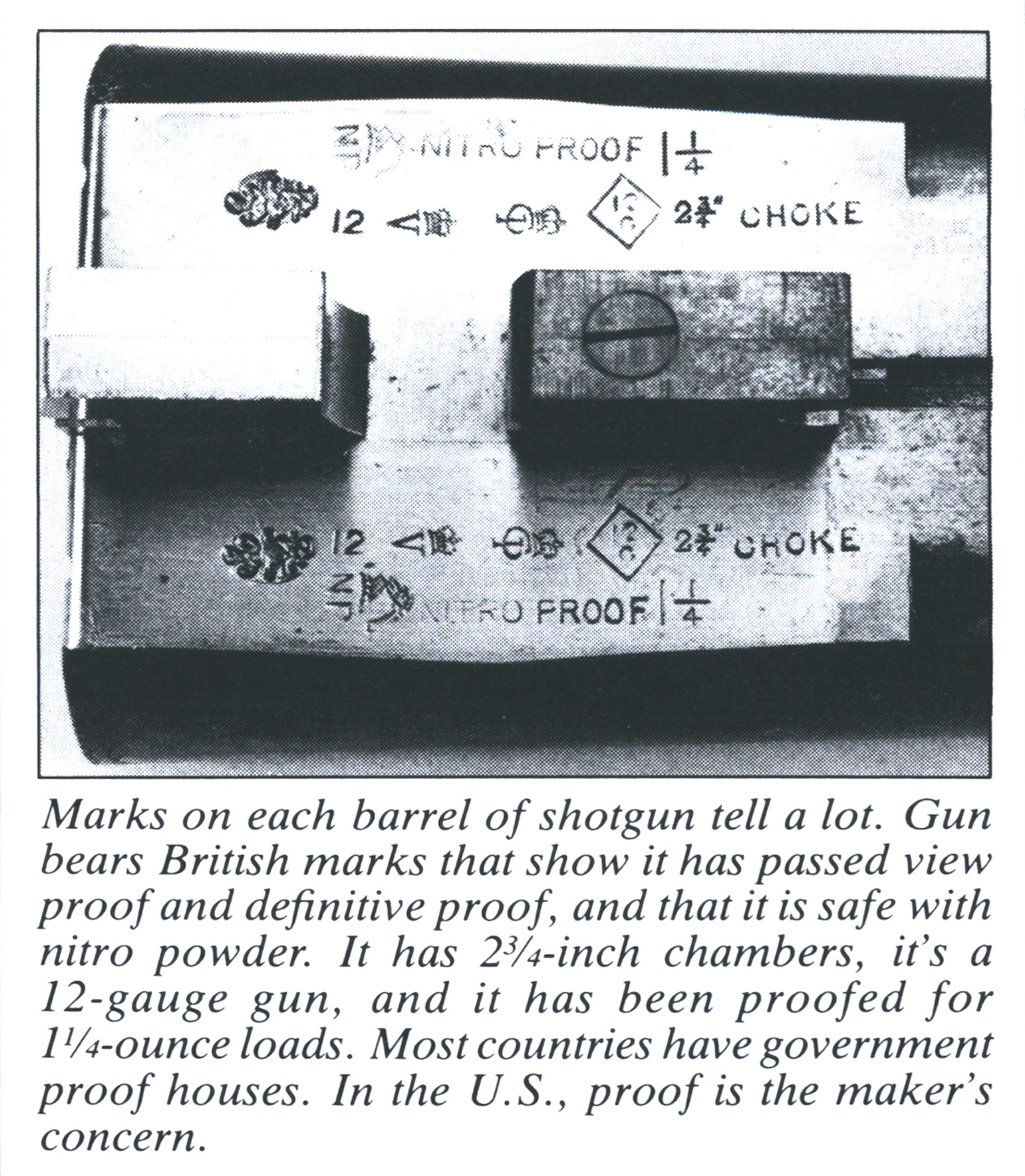

You’re probably feeling sorry for the poor gunmaker who labors to turn out a masterpiece, only to have it blown to smithereens by the proofmaster. To avoid this sad happening, a European gunmaker can now submit his new unblued barrels to the proof house for a provisional proof. If they pass, he can then proceed with finishing, stocking, and engraving the gun with reasonable certainty that it will pass the final definitive proof. If you look at the markings on a well-made European shotgun, for instance, you’ll probably find both marks.

During the last century, and to a certain extent before, there was quite a bit of competition among gunmakers to produce extremely lightweight shotguns. Unscrupulous gunmakers were known to have their barrels proofed and stamped and then returned to their shops, where they would shave more metal from the barrels to reduce weight. Anyone caught doing this was severely fined.

As you would imagine, the advent of smokeless nitrocellulose powders caused considerable reshuffling of proof regulations. Barrels that easily withstood the stresses of old-fashioned black powder were ripped apart by the tremendous forces generated by the new nitro powders. New standards of proof were established, with special markings for guns that passed the nitro proof test. Owners of older guns who wanted to use the new smokeless powder cartridges were invited to submit their guns to the proof house for retesting. The sad result of many of these re-proofings was destruction of many favorite shotguns. When inspecting the sprinkling of proof marks on a European gun, you may find a “view” proof mark. On British guns this a V topped with a crown. It means that the barrels or the action passed the visual inspection of the proofmaster or his deputy. The British are very insistent that a gun should look right. Some American manufacturers have been acutely chagrinned to discover their guns couldn’t get by the visual tests.

U.S. Proofing

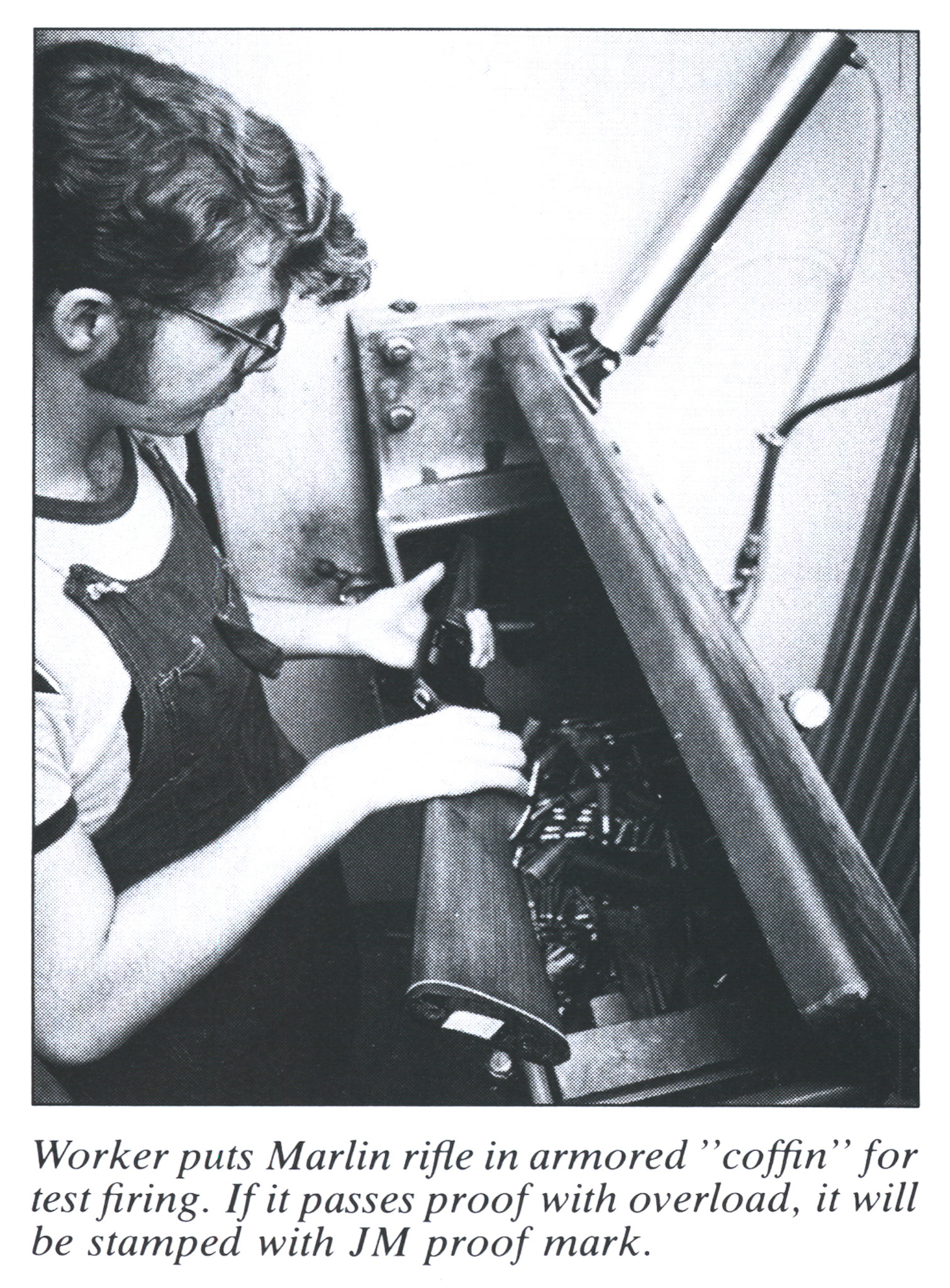

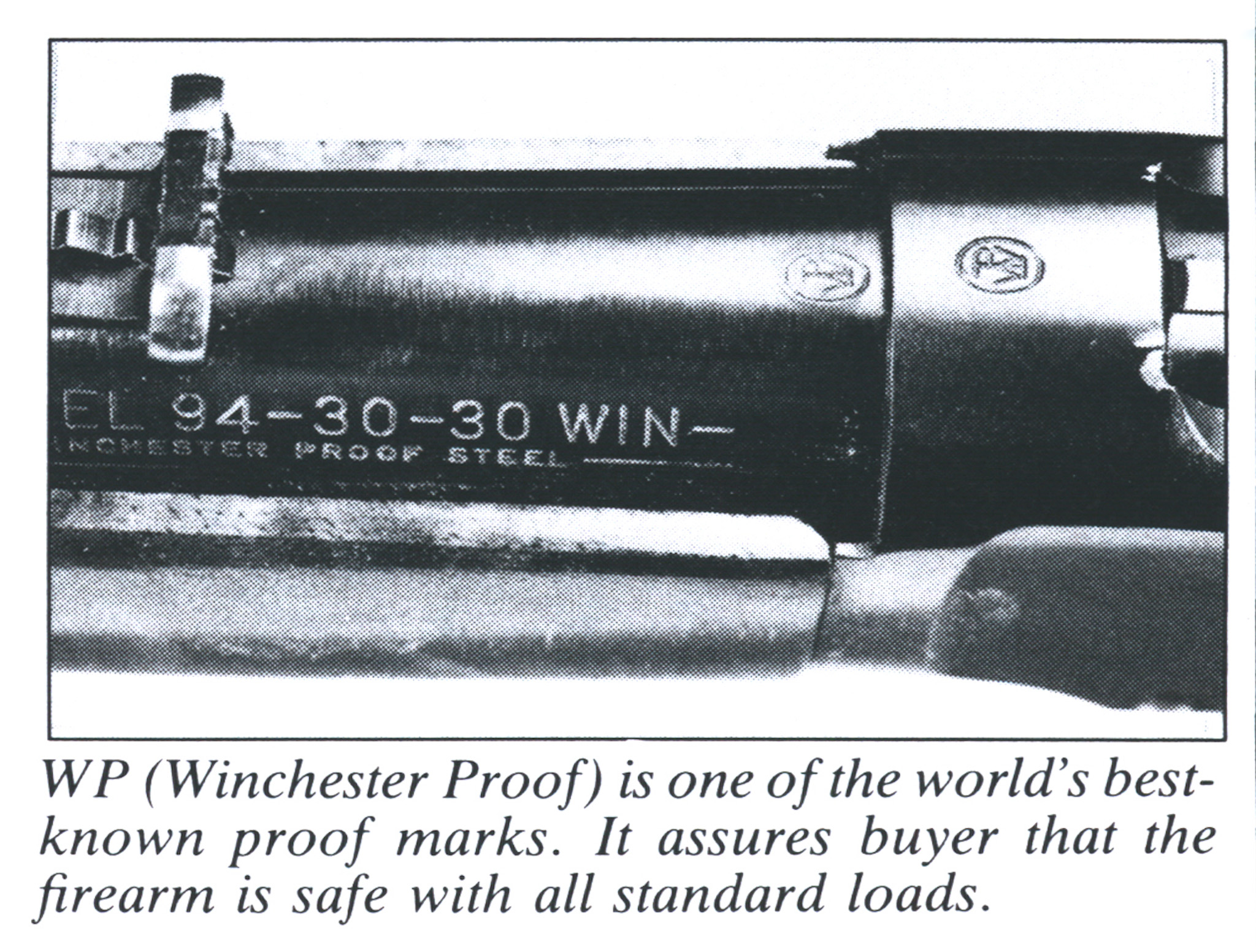

Strange as it seems, there are no proof laws in this country governing the testing of sporting arms. The matter is left to the manufacturer. (There are strict proof regulations for military small arms, however.) That does not mean that U.S. made commercial guns aren’t proof tested. All of the major manufacturers test each gun with a special “blue pill” cartridge that is loaded to about 50 percent above normal pressure or to whatever pressure level the manufacturer deems proper. Some revolver manufacturers fire a proof load in each chamber, a commendable practice; others fire only a single proof round. Some American makers do not stamp their guns with proof marks even though the guns have been rigorously proofed.

Read Next: Classic American Shotguns, According to Carmichel

Usually, the proof testing is done with the gun held in a cradle and surrounded by an armored hood, or “coffin.” The U.S. proof loads for shotguns are identified with very bright colors; centerfire-rifle and handgun “blue pills” usually have special nickel cases, and the bullet and the case head are painted a deep red. If you’re a handloader and happen to run across a good buy in fired cases that are nickel-plated and have red case heads, you’ll be smart to pass them by. The primer pockets are often so expanded that they can’t be safely reloaded. Don’t be concerned because there are no proof laws in the U.S. The strongest guns in the world are made in America. That’s why the government hasn’t had to step in with regulatory legislation, and that’s what gives justified confidence in American firearms.

The post Why Most Guns Don’t Blow Up appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/guns/why-most-guns-dont-explode-proofing/