Classic American Shotguns, According to Jim Carmichel

We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

This story, “The Classic American Shotgun,” appeared in the November 1998 issue of Outdoor Life.

Picking the classic American shotgun is a lot like being the judge at a beauty contest: You end up making a few people happy and a lot more unhappy if you don’t happen to pick their personal favorites. The choosing process is made all the more tedious by the rather sobering fact that America does not have a great shotgun-making tradition, certainly not compared to the European classics. I can hear gasps and squawks of protest, but the facts speak for themselves. We’re a nation of pistoleros and riflemen and have been ever since the days of Eliphalet Remington, Sam Colt and Oliver Winchester. When it comes to making great revolvers and lever-action rifles, we wrote the book. But where’s the great American shotgunmaker? Of course, our native-born John Browning comes to mind, but his smoothbore masterpieces — the superb Superposed and ubiquitous square-backed auto loaders — were made beyond our shores.

To be fair, our shotgun-making industry can be reasonably compared to the American automaking industry, whose vehicles are tough, reliable and generally comfortable in their fashion. But in no way do they compare with, say, the British Rolls Royce or Italy’s Ferrari, comparisons that are curiously coincidental when you consider that England and Italy are also the homes of some of the world’s truly great shotguns. So, bearing in mind that the only American-made smoothbore that comes close to the elegance and workmanship of the great guns by Boss, Holland & Holland, Purdey, Fabbri and Famars are being made right now in a modest factory called the Connecticut Shotgun Mfg. Co., I’ve bent the definition of “classic” to conform with the broad-shouldered, rough-and-ready ways we Americans use our shotguns.

Photo by William W. Headrick / Outdoor Life

The Doubles

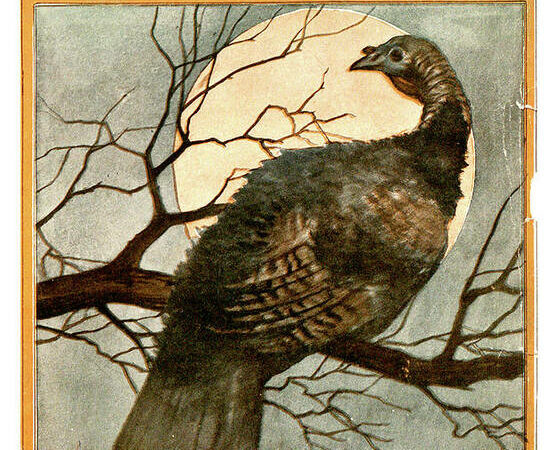

Though we sometimes get blubbery and teary-eyed about our nice old Parkers and L.C. Smiths, such emotions are generally reserved for fireside remembrances and quasi gentlemanly tomes. The somber fact of the matter is that the stars of American breech-loading — side-by-side doubles — rose and fell within the brief generation that lasted from the introduction of the self-contained shotshell until American hunters turned en masse to guns offering greater firepower. During that era of unrestrained American manufacturing virility, the prince of shotguns was Daniel Lefever. Had “Uncle Dan” been as good a businessman as he was a gun designer, Lefever might very well be the signature brand in American shotgun-making.

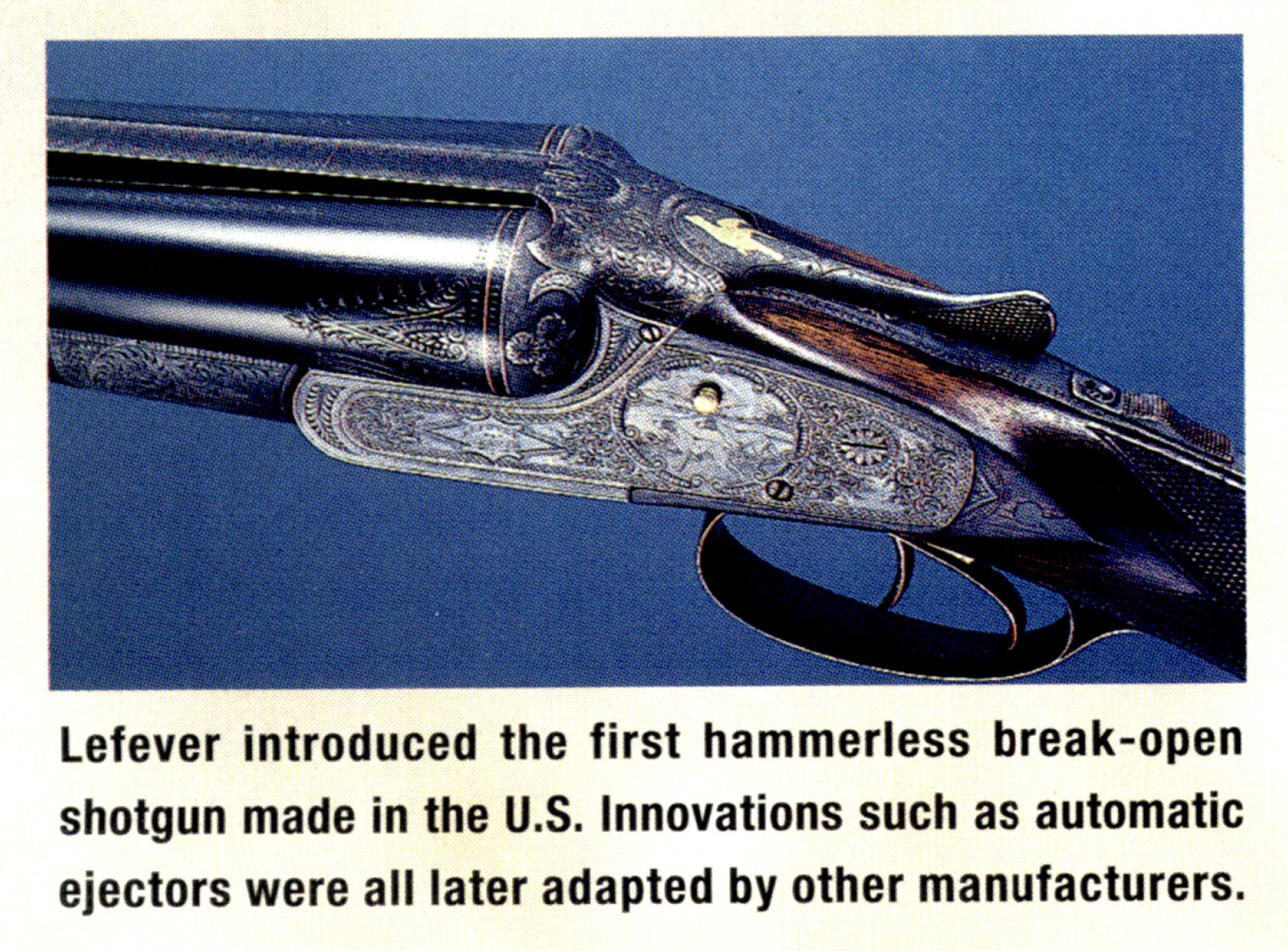

Back in 1878, when other gunmakers were still of the old-style, external-hammer mind-set, Lefever introduced the first hammerless break-open shotgun to be made in the U.S. This revolutionary concept was quickly adapted by other gunmakers and it is not unreasonable to say that other Lefever innovations such as the doll’s head breech interlock and automatic ejectors made the Parkers, Foxes and Smiths of that era better guns than they would have been without his showing them how.

The classic Lefevers are those made in Syracuse, N.Y., from 1885 to 1916, and though they had a boxlock mechanism, they are often thought to be sidelocks because of their removable side plates. Made in several grades ranging up to the ornate Optimus, the Lefevers were noted for their effortless opening and closing. Work one with your eyes closed and feel the velvety smoothness, and you’ll understand why the Syracuse Lefevers represent American shotgun-making at its best.

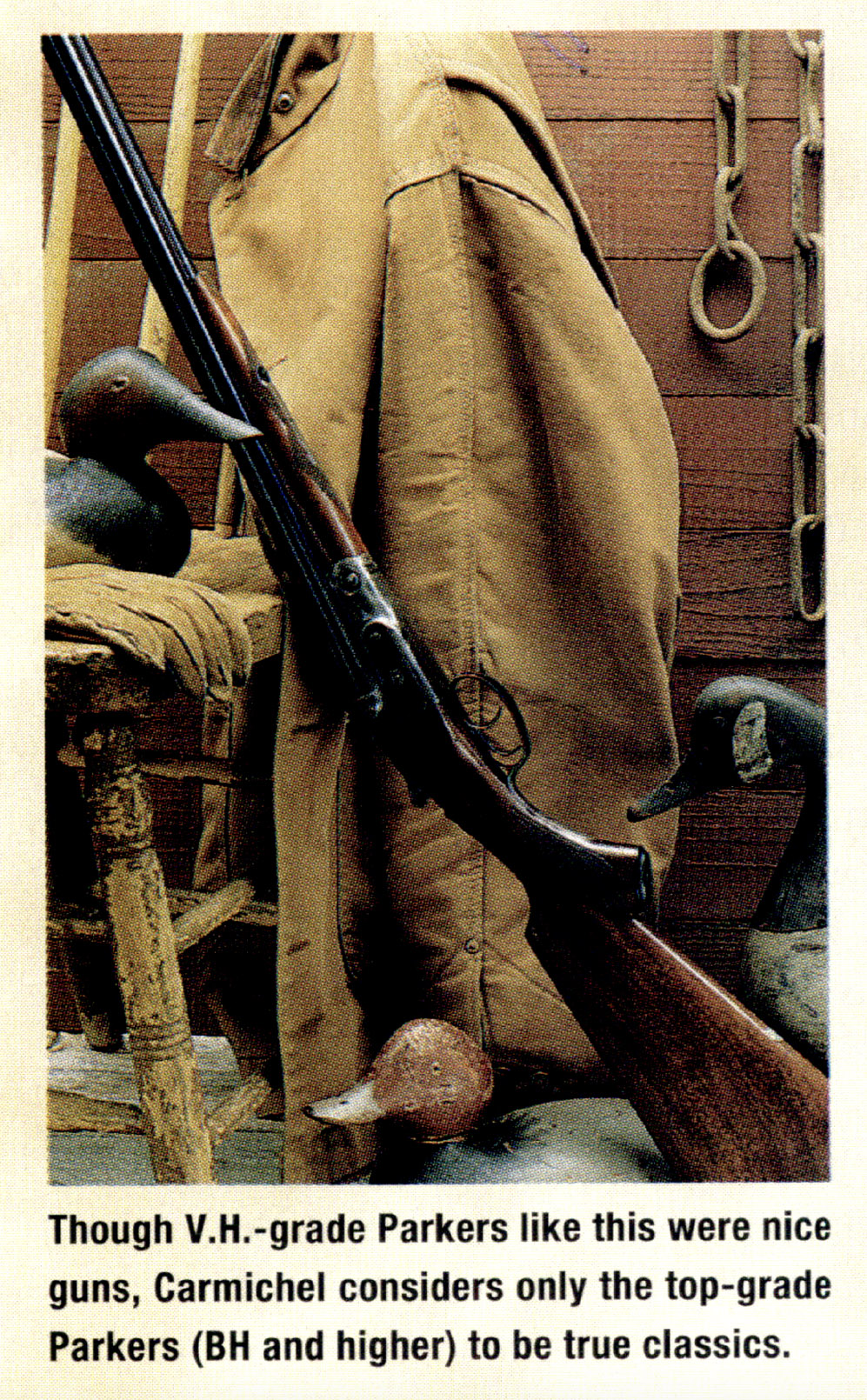

I dawdled a long while before listing Parker shotguns as American classics because I know many of the smooth bore cognoscenti will challenge the selection. But even if they do tend to be more polish than spit, as their critics claim, few will deny that the name Parker Brothers is at least the symbol of fine American shotgun-making.

During the Civil War, Charles Parker, a Connecticut industrialist, added to his already considerable wealth by manufacturing muskets and other war implements. After the cease-fire, he and his sons formed the Parker Brothers Gun Co., and one has to wonder if perhaps the elder Parker set his boys up in the gun business mainly to give them something to do. None of the Parkers seemed to have any special talent for gun design and during the war had been content to manufacture guns of someone else’s design — a philosophy that was obvious with their first shotguns, a substantial if not exceptional breechloader similar to other guns of the time. Likely, the Parker design would have seen few changes had not the whirlwind genius of Dan Lefever swept across the shooting scene. The Parker boys, even if they were not great designers, knew a good thing when they saw it and had a talent for borrowing an idea and making it even better. Lefever innovations such as the hammerless profile, doll’s head breech interlock and automatic ejectors were adapted and refined by the Parkers.

The Parker family also had refined tastes — call it snobbery — and were especially picky about the overall quality of their higher-grade guns, one piece of evidence being that they boldly advertised their use of better-quality steel in the barrels of their higher-grade guns. Another was that they sought out and employed the best engravers, fitters and stockmakers available, but, again, only for the making of their top guns. This is why, should you examine the fit and finish of, say, the “BH” and higher grades, you’ll see that all Parkers were not created equal. That’s why the truly classic Parkers are the relative handful of high-grade specimens — the finest of which is said to have been made for the Czar of Russia. The Parkers I like best are those trim little 28s.

The double-barreled shotguns made by Ansley H. Fox in his Philadelphia factory are classics for the simple reason that they are the most beautiful shotguns ever made in America and, for that matter, among the most beautiful boxlock designs ever made anywhere. Whereas the customary practice of gun invention was to design from the inside out, often enclosing the mechanism in a plain outer shell that required engraving or other embellishment to be presentable, the seductive lines of the Fox receiver suggest that it was sculpted by an artist. Like a lush maiden shed of her arrayment, the Fox needed no engraving to accent its sensuous contours and, indeed, the unadorned lowest grades perhaps best showcase their elegance of form. Small wonder that when the Connecticut Shotgun Mfg. Co. set out to recreate an American classic, its choice was the A.H. Fox, making it the only turn-of-the-century American double still being made and, for the record, better than ever.

The intent of the M-21 was noble, but somewhere along the way the idea became corrupted and the working man’s double became a trinket for the wealthy.

What about the Model 21 Winchester? Should it be considered an American classic? It’s the only side-by-side double still being cataloged by a major U.S. gunmaker, and anyone owning a 21 has reason to be proud. They are, after all, good looking and certainly expensive. But do they fall short of being classics because they have not been true to their roots? When introduced in 1930, the Model 21 was a “working man’s” double, engineered to be made by modern manufacturing techniques and sold at a modest price. In 1939, for example, the basic M-21 sold for about $70, which was only half again the price of Winchester’s standard Model 12 pump gun. The intent of the M-21 was noble, but somewhere along the way the idea became corrupted and the working man’s double became a trinket for the wealthy. Perhaps the powers at Winchester realized that the only way their beloved M-21 could survive would be as an ornate product of their custom shop. For this they deserve credit, because the M-21 is a great American shotgun, even if it lost its roots. Rumors of the M-21’s demise have been circulating for years, but it is alive and being made as good as ever in a small Connecticut shop not far from where it was born 68 years ago.

Remington’s M-32 O/U

Back when the world and I were young, a handful of the town gentry would get together on Saturday afternoons for a few rounds of informal skeet at a cow pasture skeet club. It was a six-mile bicycle ride from the farm where I lived, but I’d be there without fail, cheering every time a shooter hit a target (which occurred about half the time) and pestering everyone with wide-eyed questions about their guns, ammo or any other shooting matter that came to mind.

When I got a bit older and stronger they let me operate the massive hand-cocked traps and paid me with a couple of boxes of shells and two rounds of skeet. Stepping up to a shooting station with a gun under my arm was the closest thing to heaven I could imagine. Of course, I owned no skeet gun but could usually borrow any of the shotguns on the rack, which were mostly an assortment of Model 12 pumps and Remington auto-loaders. Some of the guns I can still recall, right down to the grain patterns of their stocks and how they kicked my scrawny shoulder like thunder. But my most vivid memory was of an always elegantly attired (at least by my farmboy reckoning) swell who drove a Jaguar sports car and strode the skeet stations with a Model 32 Remington casually dangling over his dapper shoulder.

He let me shoot a few rounds with the trim over/under and it quickly became my favorite. Whereas the pump guns had to be shucked like lightning for the doubles targets (a long reach for my short arms), and the autoloaders cycled with a double shuffle that rattled my teeth, the M-32 responded so sweetly I wondered why anyone would want any other type of gun.

The other shooters in that group, all possessing shooting wisdom beyond my comprehension, did not seem to be at all impressed by the M-32. After all, that was the 1950s and an over/under was still an oddity in many shooting circles, the prevailing notion being that they were just side-by-side doubles turned edgewise. The barrels of the M-32 weren’t even joined by a rib, and back then everyone who knew anything about doubles knew that the barrels were supposed to have a rib between them. How could the guys at Remington have been so dumb? No wonder they quit making them, and good riddance!

Actually, production of the M-32 was suspended because of W.W. II and, like several other fine guns, it did not fit into postwar production methods. With the boom of skeet shooting in the early 1960s, over/unders became the guns of choice, and prices for the few available M-32s (only about 5,000 were made) soared when shooters discovered that their only fault had been being three decades ahead of their time.

Ithaca’s Single-Barrel Trap

Single-barreled shotguns are usually associated with the low end of the market, but when Ithaca introduced its one-barrel, break-open trap gun in 1914 it was one of the finest — and most expensive — shotguns ever made in America. Designed expressly for trap shooting, the Ithaca singles were produced in 12-gauge only, with each gun being virtually handmade and individually tuned for a crisp trigger-pull and maximum pattern efficiency. To say that the single excelled in trap competition is an under-statement, because for decades it dominated the sport and spawned a genre of imitations by other gunmakers.

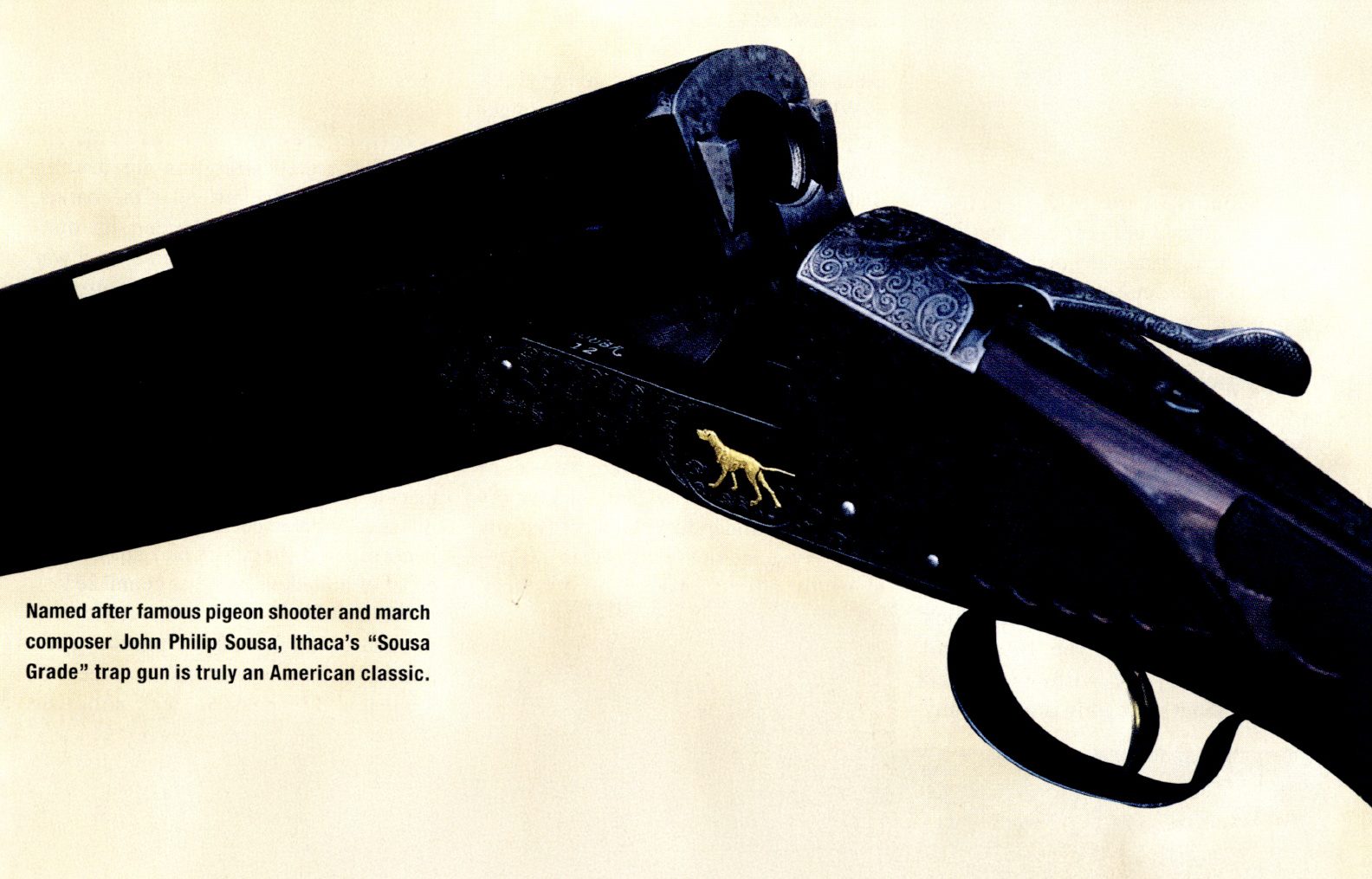

When John Philip Sousa wasn’t writing marching hymns or parading his famous band down the Main Streets of America, his passion was shooting pigeons — both live and clay. Apparently he marched a pretty wide swath in trapshooting circles because Ithaca named the fanciest grade of its single-barrel trap gun after him. A gun that, like the March King, was to become an American classic.

The Pumps

After following false trails with its lever-action Model 1887 shotgun, Winchester found the pulse of American shotgunning in 1897 with its model of that year, and we were soon a nation of shuck-gun wingshooters. Designed by John Browning, the Model 97, with its distinctive exposed-hammer profile and five-shot magazine, came in several variations, including a lethal, short-barreled “trench” model that saw service in both World Wars. Discontinued in 1957 after over a million had been made, the Model 97 is a classic because it set the tone of American shotgunning for the century.

When American hunters fell in love with the Model 97 and its breathtaking firepower, it was the beginning of the end for the side-by-side double. Any doubts about the pump-action shotgun being the wave of the future evaporated in 1912 with Winchester’s hammerless Model 12, a gun that for nearly three-quarter of a century was the symbol of American hunting and clay-target shooting. In my opinion, the Model 12 Winchester is the American Classic, because more than any other shotgun it typifies American style wingshooting and the uniquely American way of making a good gun.

The chief rival of the Model 12 was Remington’s Model 870 pump. Introduced in 1950 and utilizing postwar design and manufacturing techniques, the plain-looking Model 870 seemed at the time to be a poor shadow of the great Model 12 and got more than a fair share of snickers because of its “pot metal” trigger guard assembly, stamped parts and simplistic bolt design. But now, with production over 6 million and counting, the 870 is universally recognized as a masterpiece of engineering and one of the most ruggedly reliable shotguns ever taken afield.

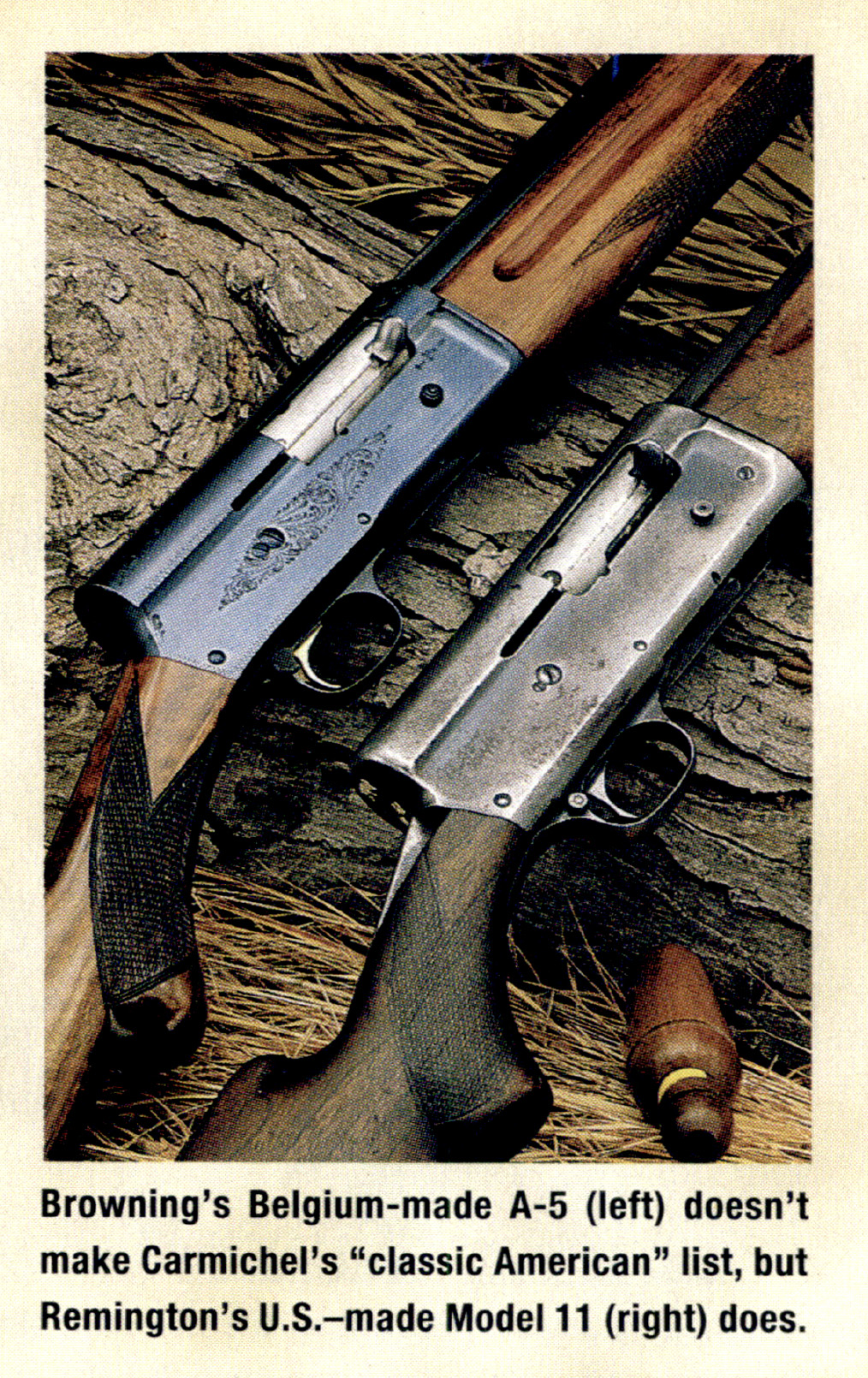

The Autoloaders

The 20th century was scarcely a month old when John M. Browning filed a patent for a shotgun that was to be known as the “squareback” autoloader, the most universally recognizable profile in any shotgunning venue. This revolutionary shotgun was first made in Belgium beginning in 1903, but in 1905, after acquiring U.S. manufacturing rights to Browning’s patent, Remington began making the “American Browning,” calling it the Model 11. Though the M-11 lacked the gloss and pretty hand-engraving of the Belgian version, it was just as well made and ruggedly dependable, and for nearly half a century it was America’s autoloader. No other attempt at making an autoloader came anywhere close to equaling its success or reputation for reliable performance.

As good as the Browning design was, its death knell was quietly sounded in 1956 by a plain-looking Remington autoloader that few shooters even noticed. What was different about this shotgun, called the Model 58, was that it was gas-operated. Whereas the famous Browning design was recoil-operated, a mechanism characterized by the barrel recoiling into the receiver with every shot and creating a jarring “double shuffle” effect, the mechanism of the M-58 was relatively simple and the barrel did not move. This made the gun feel much smoother when it fired, with noticeably less jump and recoil.

Read Next: Jim Carmichel’s Favorite Deer Rifles

The M-58 was discontinued after only a few years of production, but the gun it spawned — Remington’s gas-operated Model 1100 — can be reckoned one of the greatest firearm developments of the century. More than 3 million M-1100s have been made, and the endless list of trap and skeet championships it has won is indisputable proof that this brilliantly engineered American classic is also one of the most shootable shotguns ever made.

The post Classic American Shotguns, According to Jim Carmichel appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/guns/classic-american-shotguns-jim-carmichel/