Hunting Goats in Hawaii Isn’t Especially Hard. It’s Packing Them Out That’s the Problem

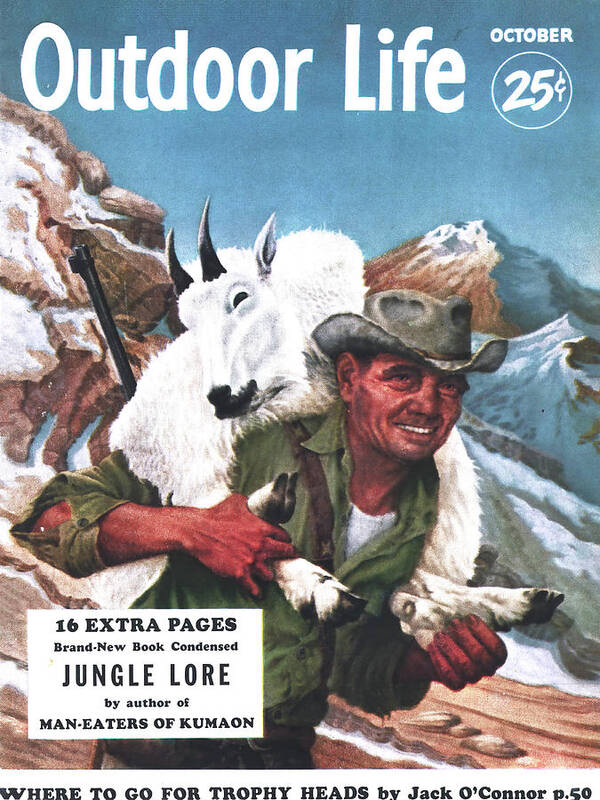

This story, “Hunting the 50th State: Goats Over the Gulches,” appeared in the June 1961 issue of Outdoor Life.

THE AVERAGE MAINLANDER thinks of Hawaii only as a tropical paradise where hula dancers sway, trade winds blow, and luxurious hotels beckon. Few realize that there’s excellent big-game hunting here, especially on several of the “outside” islands.

Take, for example, the island of Lanai-one of the lesser-known of the populated islands-where I put in a hitch as resident wildlife biologist for the Hawaiian Division of Fish and Game. The island is entirely owned by the Dole Corporation. producers of pineapple products. Because of its status as a privately owned island, Lanai is rarely visited by tourists. In fact, most residents of Honolulu — about 60 miles to the northwest — believe that it’s just one big pineapple field.

The truth is, however, that only the central plateau of the 141-square-mile island is under cultivation for pineapples. Most of the remainder — some 60,000 acres of brushland and forest — has been turned over to the Hawaiian Division of Fish and Game for administration as a public hunting area.

Lanai, far from being restricted to visitors, is open to public recreation. Most of the island’s 2,300 inhabit ants are concentrated in Lanai City, a cool, New Englandlike plantation town in the center of the island at an elevation of 1,600 feet. This leaves plenty of unpopulated elbow room beyond the pineapple fields for hunting. fishing, hiking, and camping.

The Lanai Game Management Area is open to gamebird hunting (pheasants, chukars, Japanese quail, and lace-necked and barred doves) each fall, usually from mid-October through December on Sundays only. We also have a good-size herd of the beautiful, spotted axis deer-available to the general public nowhere else in the United States except on the islands of Lanai and Molokai. Last but not least, we have goat hunting that is rugged enough for just about any hunter.

“Goats?” you ask. “Who wants to shoot an old goat?”

Well, let me tell you a little about our goat hunting. True, our wild goats once were the common, back-yard variety of billy goat, but that was long ago. For over 100 years they’ve been running wild on the slopes of Lanai’s rugged gulches; over the decades our goats have evolved into fairly decent game animals.

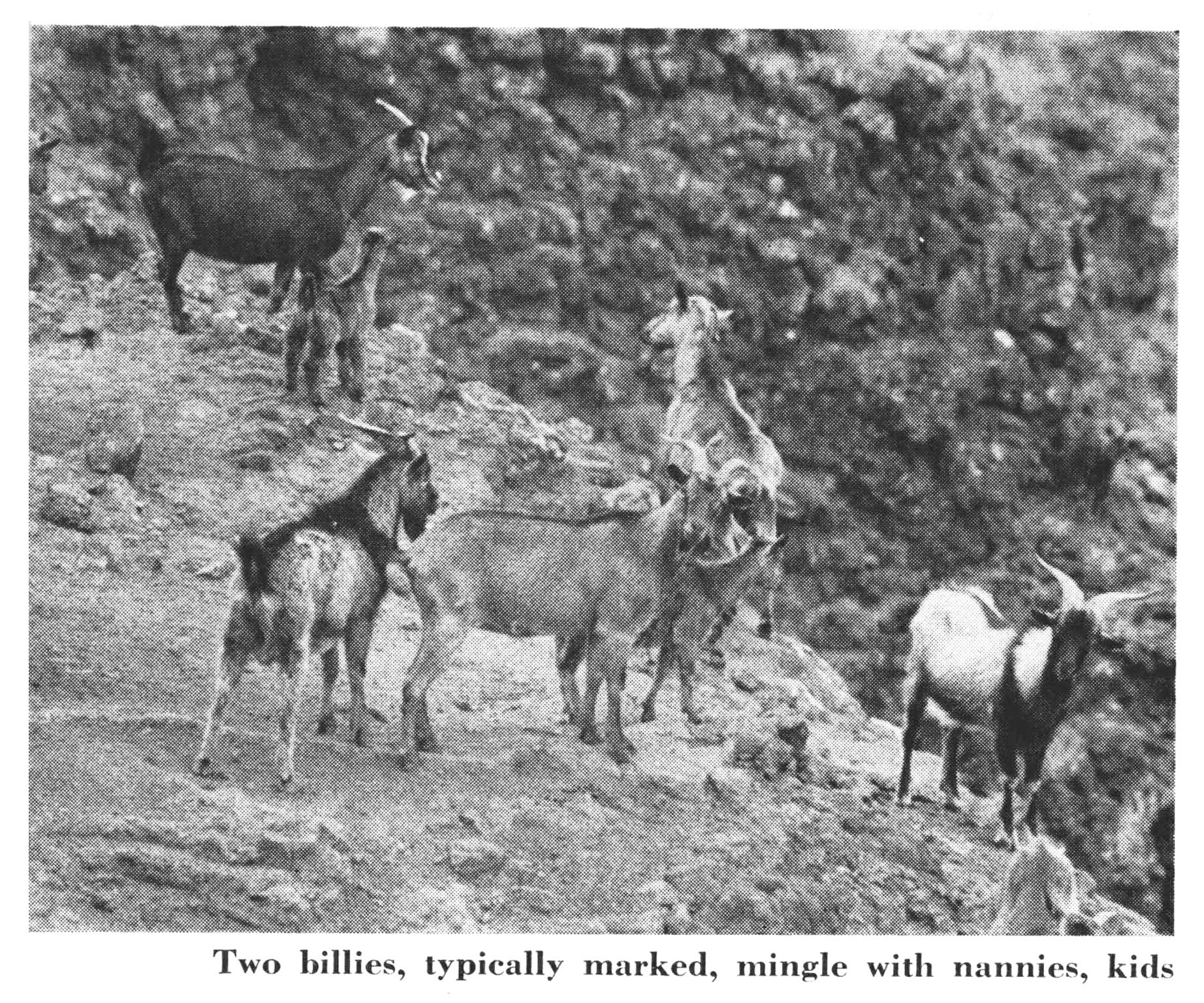

The billies have developed a rather uniform coloration: the over-all coat may be black, brown, or cream colored, but always there’s a heavy black stripe down the back, and another across the shoulders (see photo). One of those cream-colored, black-striped hides makes a handsome rug. Horns may be the back-sloping, common-goat type, they may point straight out with up curving tips, or they may be anything in between.

A good set with a spread of about 30 inches makes a dandy trophy.

These animals still smell like goats, especially the old, trophy-size billies, but then an old mule-deer buck in the rut is no bouquet of roses either. Goat flesh is edible, and if prepared right is mighty good. In fact, a lot of the local hunters really prize goat meat, and they don’t stop with the roasts and steaks. But more about that later.

The real lure in the hunting of these goats is the country they inhabit. The Hawaiian Islands are by no means made up entirely of palm-fringed beaches. On Lanai, for instance, the top of the island is a long, densely forested ridge, Lanaihale, a bit over 3,300 feet above sea level. The main ridge drops off on the windward side in a series of knifelike fingers that descend to the ocean in a run of four to 10 miles. These fingers are separated by deep gulches, some of which are well over 1,000 feet from ridgetop to bottom. Their sides are fearsomely steep, and are composed of a loose, crumbly mixture of soil and rotten-lava rock. Climbing these sheer faces is a real adventure.

Although the top of the main ridge, and the upper limits of the finger ridges, reach into the cloud belt and are covered with a shrub and fern jungle, the biggest part of the finger ridges is open, laced here and there with grass and scattered shrubs, and dotted by small groves of trees. These ridges and gulches look some what like the desert mountains of northern Mexico, being sparsely covered on top, and bare and precipitous on the sides. Goat territory runs from the lower edge of the fern forest down to an elevation of about 500 feet.

There are two main access routes into this rugged goat country. One way is to drive your jeep from Lanai City down the one paved road that leads to the northeast (windward) coast, and then follow the coast road-a mere jeep track that runs along the beach and through the coastal keawe (mesquite) forests for some 11 miles — to the seaward end of a chosen ridge. There you leave the vehicle and fight your way on foot through half a mile of thorn bush until you reach open country and start climbing.

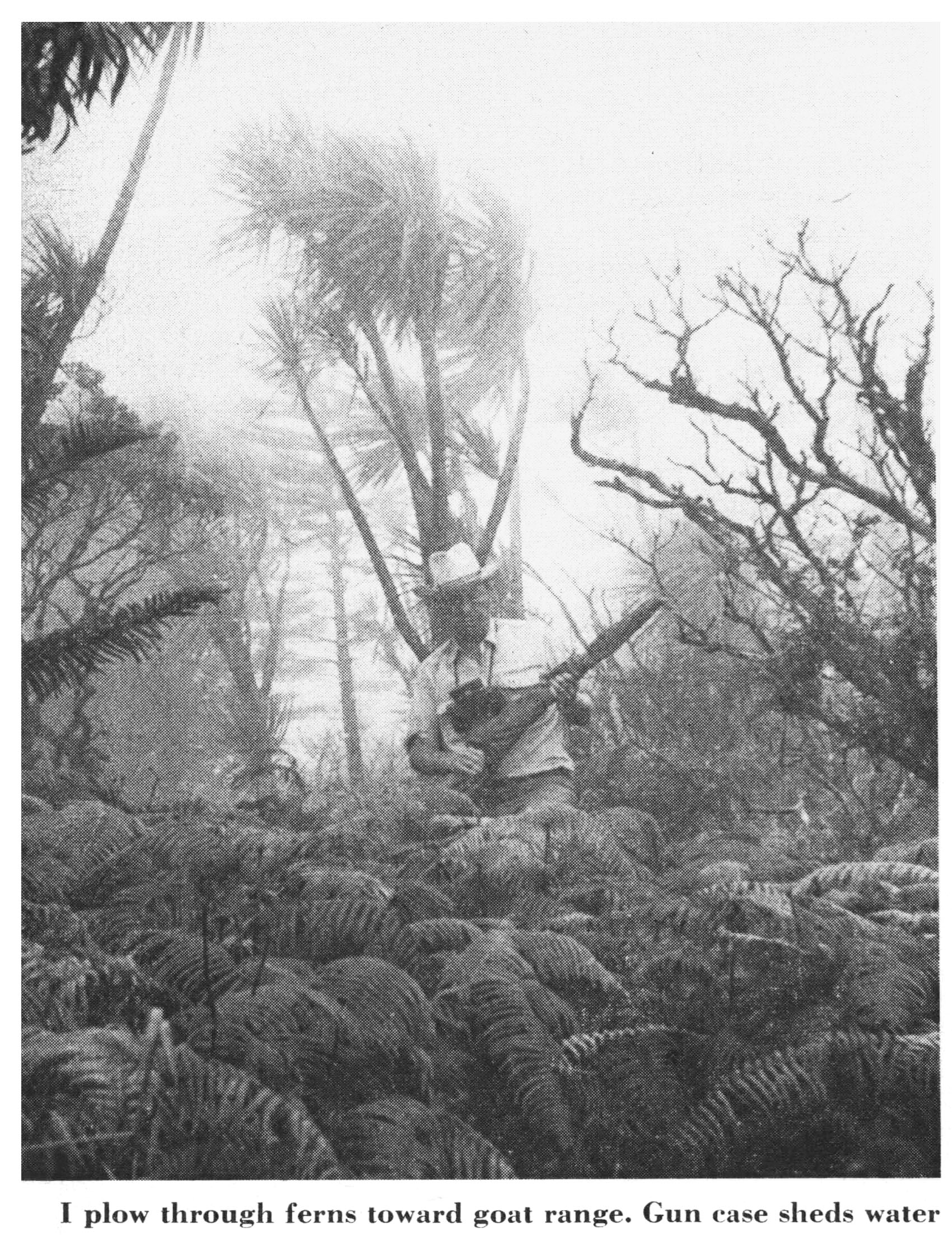

The other way is to drive up the jeep road that runs from end to end of the main mountain ridge. Again, you must leave the jeep on the road-this time at the head of the ridge you’ve chosen — and take off on foot down through a mile or so of fern jungle until you hit the open ridge.

Each way has its advantages and disadvantages. If you climb up, the distance is greater and the heat worse, for the lower you are, the hotter it is. But when your goat is bagged, you lug it downhill. If you start from the top, it’s pleasant going down, but a tough job packing a goat back up.

Most of the local boys hunt on foot, but a few do it on horseback. However you travel, you just don’t hunt cross-country in the biggest part of the goat area, not unless you like to climb down as much as 1,000 feet on a sheer wall of loose rock, and then climb back up another of the same to get on the next ridge. It can be done in some places, but your insurance company won’t like it much if you do.

There’s one jeep road running down the ridge next to Awehi Gulch from the top of the mountain to the coast road in pretty fair goat range. As you’d expect, the slopes near this road, which are somewhat easier to scale than most, get plenty of pressure from the boys who don’t care for long, hard walks. Chances for a good trophy, however, are not too good near the road. Before I came out here I lived in Colorado where I spent a lot of time in the Rocky Mountains working as a cowboy, dude wrangler, and later as a student at the Colorado State University, where I was trying to absorb enough knowledge for a couple of degrees in wild life management. In the course of my ramblings I used to crawl around just about anywhere that didn’t require pitons and ropes, but the footing there is usually reasonably solid, even on the steepest slopes. Here it is anything but solid; the loose, rotten-lava rocks are like walking on precariously stacked tennis balls. I wouldn’t climb down into some of these gulches for a worldrecord bighorn sheep; well, maybe…

But the goats love this terrain. When undisturbed, they spend a lot of time on the ridgetops, but don’t mind rambling about on the sheer slopes. They go all the way to the bottom for water, then back to the upper walls and ridgetops to graze and rest. They run, play, feed, and sleep on inclines that would make a steeplejack dizzy.

When hunting the ridges between the larger gulches, the trick is to catch the goats while they’re still on top. This is best accomplished by spotting a herd ahead of time and stalking them, which is fairly easy to do since they aren’t nearly so alert as deer. Thus can the hunter pick his animal, carefully place his shot, and be assured of anchoring it where it can be picked up. If, on the other hand, you shoot a goat that’s standing on the wall of a gulch, the carcass usually will slide and bounce its way down hundreds of feet to the bottom, where it will probably be irretrievable. Goats that fall into less precipitous gulches can be packed out at the cost of a pint or two of sweat. But it’s a lot less work if you can manage to nail one on a ridgetop.

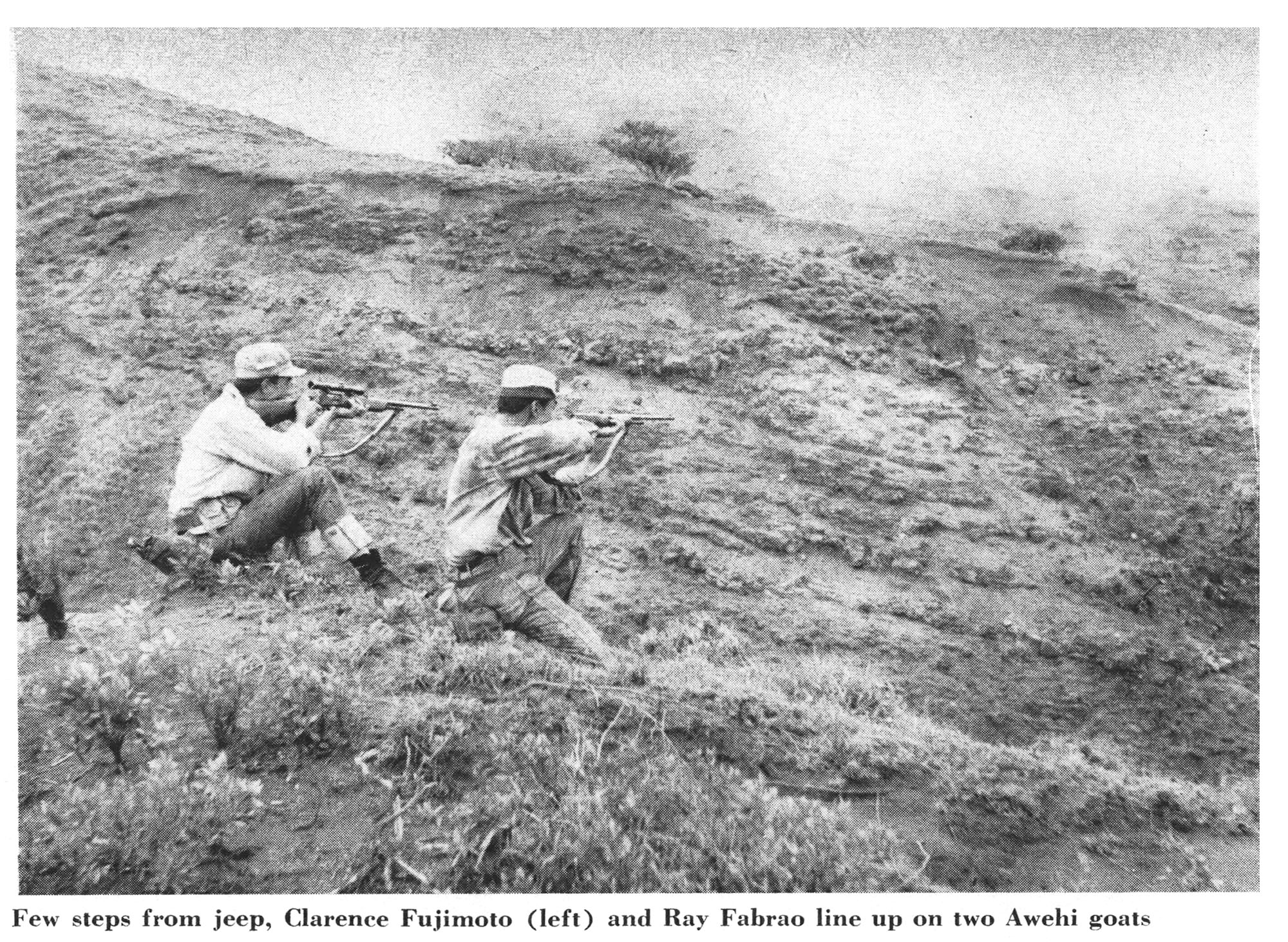

I’m sorry to say I’ve seen hunters sit on one ridge and blast at goats one or two ridges away-a distance of maybe 600 yards or more as the bullet flies. Even if they hit one and kill it, they wouldn’t dream of trying to go after it. Regrettably, this type of shooting is fairly common here. Don’t get the impression, however, that all the local hunters are careless and wasteful. Many are true sportsmen who know their game and guns, and wouldn’t think of shooting unless they were sure of dropping a goat where they could get it. A couple of such hunters are Ray Fabrao and Clarence Fujimoto, local men who work for the Dole Corporation (just about everybody on Lanai does) and take their hunting seriously. Both are good stalkers and careful shots, and were two out of only three hunters who got limits of two goats apiece in the 1958-59 Lanai archery season.

One Sunday morning during the August 1958, goat season, I met Ray and Clarence driving down the Awehi Gulch road. I didn’t yet know either of them well, but they were cheerful and friendly and not a bit averse to my tagging along to take a few photos. I didn’t expect much action, however, since this area had been hunted heavily.

My pessimism was short-lived, though. We’d hardly piled out of our jeeps when Clarence spotted a nanny on the opposite ridgetop-about 200 yards away. Since this was an either sex season, nannies were fair game; in fact, they are preferred by most hunt ers because the meat is less tough and not so gamy. Clarence jacked a cartridge into his scope-sighted Marlin .30/30, sat down less than 20 yards from his parked jeep, and carefully squeezed off one shot.

Before the smack of the bullet reached our ears, the nanny was down and out, and the easy part of Clarence’s hunt was over. At the sound of the shot, a small band of goats made the mistake of running into view from the far side of the knifelike, open ridge. When they spotted their defunct cousin, they paused and began milling about, ba-a-a-ing their nervousness (goats are very vocal, and often it’s easy to locate a herd by the noise before you see them).

They didn’t pause for long, however, for Ray touched off one of his own from his Winchester Model 64. Down went another nanny, making the score two one-shot kills with .30/30’s at a good 200 yards. This time the herd disappeared back over the ridge in a cloud of dust and rolling rocks.

Clarence and Ray walked the few steps back to their jeep and put away their rifles. The shooting was over less than five minutes after they’d arrived. But the work was just starting.

That 200 yards between the shooters and their game was the straight-line distance across the top of a gulch some 600 feet deep, with sides composed of the usual rock rubble and sliding soil sloping down at about 60°. An hour and a half later, after having slid and bounced their way to the bottom, crawled up the other slope, dressed their two goats, and packed them back down and up, Ray and Clarence were in their jeep and on their way home.

The only fun hunt I made on Lanai was on another Sunday in that same 1958 season. I guess I’d better tell you what I mean by fun hunt. My major job on Lanai was to do a life-history study of our axis deer. Very little was known about their breeding habits, what they ate, herd numbers and composition, or what parasites or disease might affect them. In fact, practically none of the basic information needed to manage a big-game species was available. In the late summer of 1957, the Division of Fish and Game had hired Dr. William Graf of San Jose, California, and myself to work out the facts about the lives of these deer so that they could be properly managed for hunting. Dr. Graf took over the study on Molokai, while I started in on Lanai. Ray Kramer, the biologist stationed on Molokai, has also been helping out with the investigation.

As part of the job, we’ve had to collect a number of deer and goats for post-mortem examination. Deer hunting and getting paid for it, too? It’s not so rosy as it sounds, believe me. While I hunt, I have to pack a complete autopsy kit on my back — scales to weigh the deer, block and tackle to hoist them for weighing, jars of formalin for samples, and so on, all of which detracts from the enjoyment of a stalk. Once an animal is down, it must be completely measured, weighed, examined externally for parasites or abnormalities, and examined thoroughly internally. Samples must be taken from various organs and stomach contents for future study, and the deer must be weighed again, dressed.

What I call a fun hunt is the kind on which I’m out on my own and hunting for recreation like anyone else. There’s no worry about taking samples or examining the game other than superficially for my own interest. So one Sunday in August I left my jeep on the Lanaihale road and worked my way down into goat country on the ridge above Hauola Gulch, the deepest on Lanai. As soon as I broke clear of the fern forest, I started seeing goats on the steep slopes below me. But it was no use shooting one there; I’d never be able to get it.

I was out to get the best head I could find in my one day of hunting, as well as to get some eating meat, so I carefully glassed every billy that seemed accessible. I was about two miles down from the top when I spotted a small herd of four billies and two nannies bedded down on a patch of bare dirt in a nest of small canyons to my left. My binoculars showed that one black billy had a better set of horns than any I’d seen — wide and upcurving. Not a record head, but one better than average, and of a shape to make an interesting trophy. I decided to try for him.

I was on a high point, about a quarter of a mile from the goats. It was simple to ease off my ridge into the small, broken gullies between me and the goats, and to follow a series of them to within shooting range-all the while keeping below the goats’ line of sight. As I crawled over the last small rise, I found myself in a good position for a shot, only 75 yards from the goats. A slight twinge of buck fever set the crosshairs of my scope to trembling. Even though I’ve taken more than 50 head of big game, buck fever still hits me a little. Things soon steadied down, though, and I was able to ease off a shot from the Remington .30/06. By then my black billy was standing broadside to me. When the 150-grain Norma bullet took him through the lungs, he folded like a limp dishrag. I had my trophy.

The horns were as good as they’d seemed, but not exceptionally wide — 26 inches from tip to tip. Still, they were heavy and symmetrical. The tips, upcurving more than usual, make that head one of the nicest I’ve seen.

Goat hunting on Lanai has its comic side, too. Legal hunting weapons are rifles delivering a muzzle energy of at least 1,200 foot pounds, and shotguns with rifled slugs. I once stopped to chat with an old gent who was slowly climbing the hill to the road with his trusty 12 gauge pump gun over his shoulder. He was most discouraged, and told that he’d just fired three shots at a goat, and “he no fall; I no under stan’ .”

I questioned him further, and he explained that it was an easy shot, and close, too. “The calding (goat) wasn’t far, he was just on the hill right over there, and I shot three times. He didn’t fall, and I don’t understand.”

The spot he pointed out was on the next ridge, a shot of at least 200 yards — and with a shotgun yet!

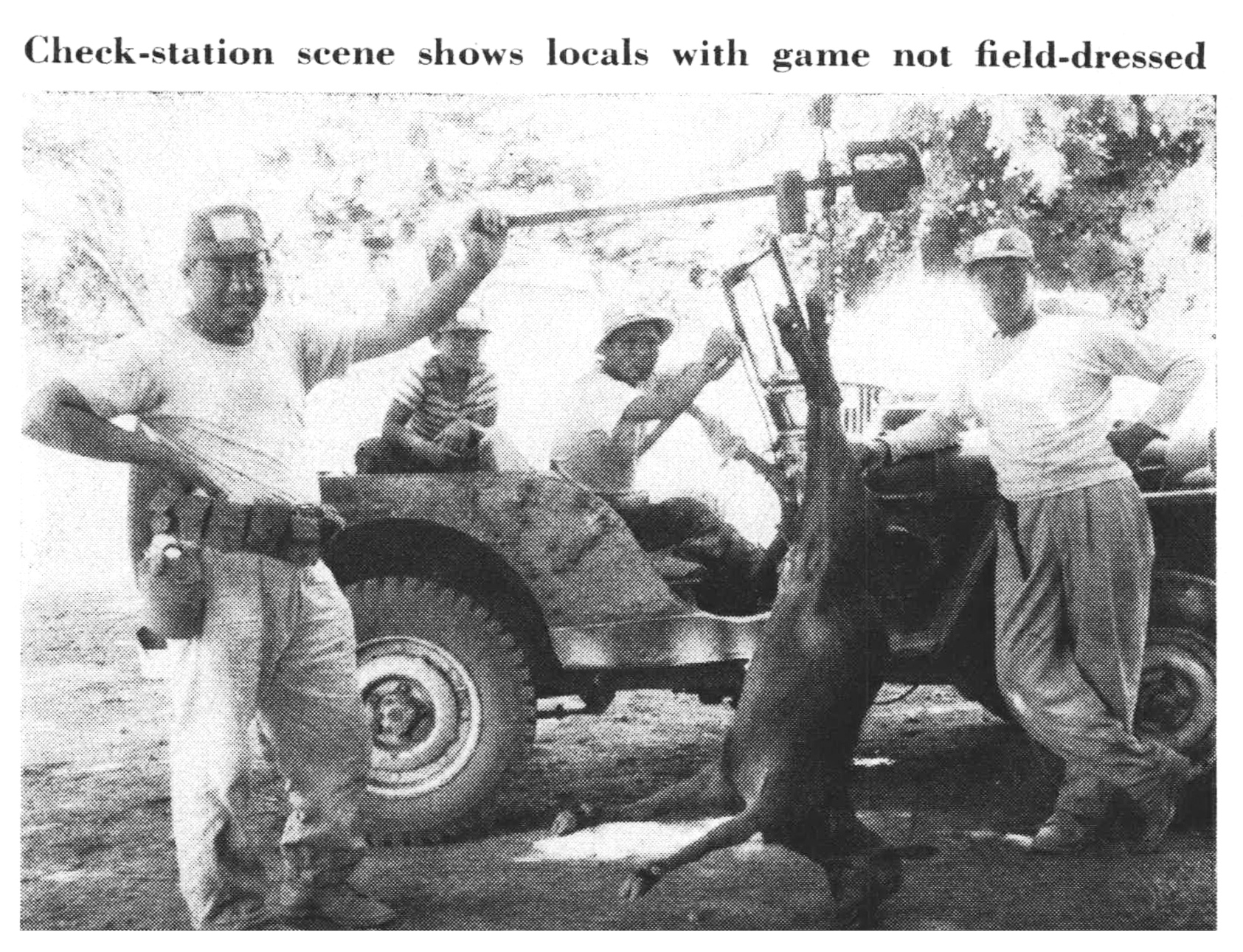

A goodly part of our local hunters are of Filipino ancestry, and do they love goat! Among their favored portions are the innards, so they frequently bring in their goat whole, ungutted. I don’t mean to run down their taste just because it differs from mine. They probably think I’m nuts because I won’t eat the real “goodies.” But to a hunter accustomed to Mainland hunting, it does seem a bit strange — especially in a hot climate — to see big game brought in without its having been field-dressed. More power to these island hunters, though; they waste less and enjoy their goat more than the rest of us.

The Lanai game warden, Dick Morita, told me that he once stopped an old Filipino who was trudging out of the goat-hunting area with his 12 gauge over one shoulder and a bloody sack over the other. When Dick asked the old hunter to let him check his game, the sack was dutifully opened and in it was nothing but entrails.

Asked where the rest of the goat was, the man replied, “I shot him in a plenty steep place. It was too steep for bring out the whole goat, so I just took the good parts.”

Again, let me say that I don’t mean to sell Filipinos short. Most of them are strictly meat hunters — few are interested in trophies. But because of their liking for roast goat, when they pot an animal they’ll do their darndest to get it out.

I saw one of these hunters drop a goat on the rim of a really steep gulch one time. The carcass bounced halfway down the slope and came to rest on a small ledge. Most people would have left it as inaccessible, but not this cookie. He looked over the edge, saw what he was in for, and calmly sat down and took off his shoes. Although these lava rocks are sharp, he went down barefooted, for a better grip on the loose rocks, until he reached his goat. Then, with the goat over his shoulder, he crawled back up on all fours until he made it over the rim and back to his shoes.

Equipment used in Hawaiian goat hunting is as varied as hunting gear is anywhere. As I mentioned before, shot guns with rifled slugs are used by some, but most prefer rifles. Shots are usually long, so flat-shooting cartridges and scope-sighted rifles are preferred. The most common caliber used is the .270, closely followed by the .30/06 and the old .30/30. The 6 mm.’s are fast becoming popular due to their long range and accuracy, and I believe that the .243 Winchester and the .244 Remington are just about the ideal medicine for all Hawaiian big-game hunting. Most of our game, with the exception of pigs in some areas, is shot in fairly open country where light, fast bullets work fine, and our largest game animal, the axis deer, is easily handled by a well-placed 6 mm. bullet.

The most important item of equipment besides a good rifle and knife, is a full canteen. The goat ridges are high and dry, and packing a goat up one of them in a tropical sun can make you plenty thirsty. A pair of good quality, lightweight binoculars are also valuable to have along. The rest is up study into their life history. Our results to date now indicate that we can have a limited open season each year from now on without reducing the basic breeding herd. The 1959 season on Lanai for axis deer ran for two Sundays, October 4 and 11, and a total of 150 permits — 130 for bucks only, and 20 for does only — were issued on a drawing basis.Each permit entitled the holder to take one deer of the sex indicated, and to hunt on one day only. Anyone may apply for the drawing. The regular hunting license is all that is needed; the nonresident license costs $10, and the resident license is $5. No guides will be required on Lanai. The island may be reached daily from Honolulu via a short flight on Hawaiian Airlines. Rental jeeps are available, but hotel accommodations may be hard to get unless you make reservations in advance at the Lanai Inn, Lanai City, Hawaii. There’s plenty of room for camping out, though.

Last year on Lanai there was a three day season for billies only from April 24 to May 8. The bag limit was one per hunter. Of the 172 hunters who participated, 95 got goats for a success ratio of 55 percent — about normal or slightly below for goat hunting here. As this issue of OUTDOOR LIFE goes to press, final dates are not available for a spring hunt this year.

Other goat seasons are set from time to time on other islands, and there are several year-long seasons such as the archery season on Lanai and a rifle season on Hawaii. In certain places, goat season is open all year long on private lands (permission to hunt is needed from the landowner) and on some forest reserves where you must get a permit from the local forestry office. On public hunting areas, goat I seasons are managed somewhat differently on each island, depending on local conditions. So it’s best to check ahead of time with the Hawaiian Division of Fish and Game office at P. 0. Box 5425, Honolulu 14, Hawaii, for the latest dope.

There are also year-long seasons for feral sheep and pigs on Hawaii, and annual hunts for axis deer on Lanai and Molokai, but these latter have been limited hunts so far, with drawings being held for the limited permits is sued. Deer seasons are usually in August or September on Molokai, and October on Lanai. Over the past two years, success has been about 33 percent on Molokai and 50 to 56 percent on Lanai on buck deer.

Read Next: Meet the Godfather of Hawaiian Market Hunting

And don’t forget, on the way to Lanai, or any of the other outside islands, you have to first pass through Honolulu. There they do have the beautiful tourist hotels and other attractions commonly associated with Hawaii. But what sportsman would want to waste a minute watching a Tahitian dancer when he could be out stalking a goat or deer? Come to think of it, maybe you better head for the game fields first before spending any time in Honolulu, or you may never unpack your rifle.

The post Hunting Goats in Hawaii Isn’t Especially Hard. It’s Packing Them Out That’s the Problem appeared first on Outdoor Life.

Source: https://www.outdoorlife.com/hunting/wild-goats-hawaii/